Chronicle of a Catastrophe Foretold

How Crawford Lake in Canada is keeping a record of humanity’s impact on the natural world – interview with geologist Reinhold Leinfelder

Jul 24, 2023

A team of researchers from Carleton University and Brock University removes frozen sections from a sedimentary core taken from the bottom of Crawford Lake.

Image Credit: Peter POWER / AFP

Just recently, the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) submitted a proposal calling for the declaration of a new period in the Earth’s history: the Anthropocene. The AWG, an interdisciplinary research group comprised of thirty-five researchers from around the world, is dedicated to the possibility of formalizing the Anthropocene as a discrete geological unit. An interview with geologist Reinhold Leinfelder, professor emeritus of Freie Universität Berlin and member of the AWG since 2012, on the significance of a small lake in Canada, how our impact on the planet compares to that of mass extinctions in the distant past – and what consequences declaring the Anthropocene could have.

Professor Leinfelder, the term “Anthropocene,” which has been proposed as the new name for our current geological epoch, was first suggested twenty-three years ago. What has changed since then?

“An impact comparable with the mass extinction of the dinosaurs.” Geologist and professor Reinhold Leinfelder is a member of the Anthropocene Working Group.

Image Credit: Jan O. Kersten

What has changed is that we now have geological and stratigraphic evidence to prove that the Anthropocene is real. This means that we are able to determine a point in time from which human activities first became traceable in sedimentary deposits across the natural world – on a global scale and in all types of deposition areas: for example, the open sea, in coral reefs, bays, lakes, and moors. Current evidence places this period as beginning in 1950.

What has also changed is that we can now prove that these geosignatures can be traced back to human activity, for example, radioactive deposits from atom bomb tests, fly ash from industrial processes, “technofossils” such as plastic particles; elementary aluminum; concrete and brick fragments; and geochemically detectable signatures from agriculture, industry, and infrastructure. However, more typical fossils can also be used to define this period, for example: diatoms that drive out other types of algae; many invasive species such as mussels and snails; and plant pollen.

Or, to put it simply: We can prove how we are having a lasting effect on nature – we tear down entire mountains, carve new valleys, decide where rivers flow, create new lakes; we decide where sediments are deposited and where they don’t, which organisms live where. We are raising the sea level and changing the climate. This behavior is permanently and visibly recorded in Anthropocene sediments.

The use of fracking technology is creating tangible earthquakes. We are even influencing how the magnetic poles move through excessive groundwater extraction, shifting the Earth’s axis of rotation.

And what does this have to do with Crawford Lake in Canada, which was recently proposed as an official site marker for a new Anthropocene epoch?

The official guidelines of the International Commission on Stratigraphy specify that, to formalize the Anthropocene as a geological period in the Earth’s history, a geological reference site must first be identified, described, and internationally agreed upon. This reference site is called a Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP). These GSSPs are marked accordingly and have to be permanently accessible to researchers.

This is similar to the official process that takes place for defining new types of organisms in the field of biology. Here, a reference specimen of an organism – a holotype – is permanently preserved in a scientific collection and made available for all scientists. It is often stored together with its paratypes in order to demonstrate the variety of a species. In geology, this reference example is the GSSP.

Why was the decision made to nominate a Canadian lake as the GSSP?

The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) was responsible for making the decision regarding the proposed reference point. This was not an easy decision to make; we investigated twelve different locations around the world using the exact same methods. They were located both in the sea (in Pacific and Caribbean coral reefs; in the Central Baltic Sea; a bay in Japan; in the San Francisco Bay) and on land – sometimes in very remote locations (for example, a deep maar lake in China; a peat bog in Poland; the Antarctic ice sheet) and sometimes relatively close to civilization (Searsville Lake in the USA; Crawford Lake in Canada; and Karlsplatz in Vienna).

An important prerequisite for the decision was that the site contain plutonium isotopes from hydrogen bomb tests as a key marker, showing the increase of sedimentary radionuclides in the 1950s as well as other geosignatures. However, it was also important to have regular – preferably annual – stratigraphic layers with which to date and track these changes.

Tim Patterson (left), geology professor at Carleton University and his team of researchers collecting layers of sediment from the bottom of Crawford Lake in Ontario. The photograph was taken on April 12, 2023.

Image Credit: Peter POWER / AFP

Crawford Lake is a particularly strong candidate in this regard because it shows a record of both global and regional geosignatures while at the same time featuring annual – and sometimes even seasonal – deposits. In doing so, it acts as an archive of human-made ecological changes and in addition even provides insight into earlier human activities carried out by the indigenous population and, later, the European settlers – the only candidate of our twelve research sites to do so.

However, the other reference points we investigated are equally interesting in their own way. It is my hope that these may serve as additional environmental archives, providing researchers with access to “typical” sedimentary deposits from a wide range of different profiles. This is a decision that will be an upcoming subject of discussion at the AWG.

Why is it necessary to officially declare a new geological epoch?

The Holocene – the postglacial epoch of the Quaternary Period in which we currently live – is fundamentally different from the Anthropocene. There is no question that the impact humans have on our Earth system can be compared to that made by the meteorite that hit Earth sixty-six million years ago, causing the mass extinction of the dinosaurs – also known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Our impact can also be compared to that of the Permian–Triassic extinction event where, over 252 million years ago in what is today Siberia, a series of gigantic, long-lasting volcanic eruptions led to Earth’s most severe known extinction event.

This is why it is so important to formalize the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch. By equating it with the Holocene, we would not be comparing apples to oranges – but rather apples to melons.

What would be the consequences of declaring the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch?

It would be of benefit to everyone. Being able to stratigraphically pinpoint the beginning of the Anthropocene to 1950 and having the ability to differentiate further isochronous “events” even in an annual resolution provide us with a precise sedimentary archive of human activity that, unlike historical archives, was not created by humans.

After all, historical archives are places where humans decide what information should be registered and stored – and where. This includes publications, annual fertilizer consumption, numbers of fish caught, insurance information on the damage caused by storms, the orbits of exploratory satellites.

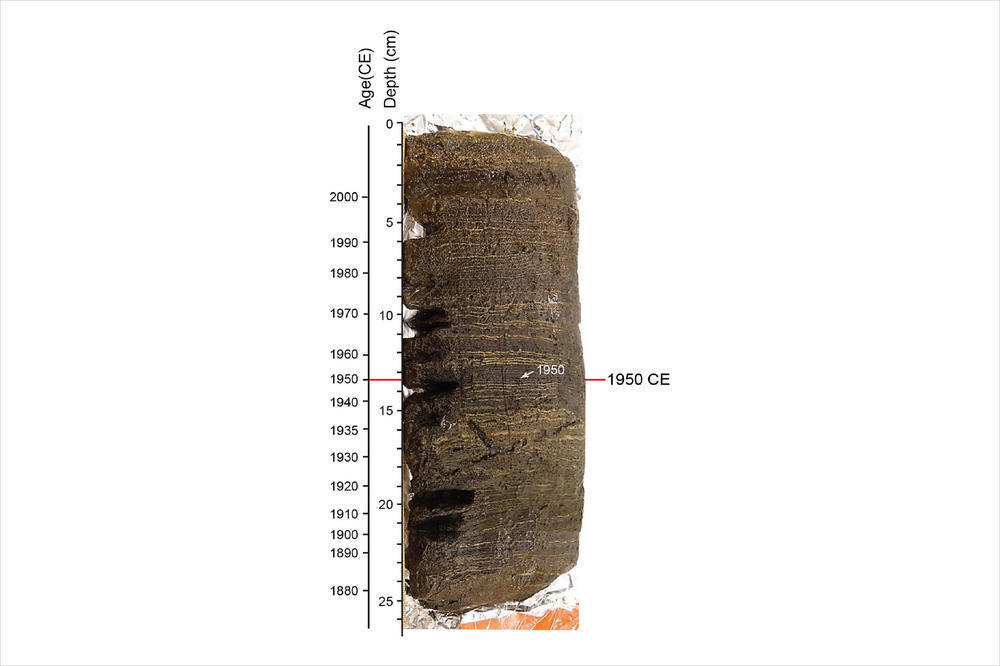

Sediment core from the bottom of Crawford Lake. Like tree rings, scientists can calculate the age of the deposit by counting the annual layers. Microscopic and geochemical analyses show evidence of human activity, such as radionuclides and industrial

Image Credit: F. McCarthy

This stands in stark contrast to a “natural archive,” where nature provides us with an “unbiased,” non-curated record of human activity. Anthropocene sediments are found around the world and in all types of deposition areas. This benefits science immensely – these data can be combined with data from archaeology and human historical archives, enabling us to create interdisciplinary analyses and automatically record progress or regress in our transformative efforts.

In terms of the Anthropocene, geological “deep time” includes both the present “Great Acceleration” and the effects thereof – the “Long Now.” The “Long Now” is a concept that aims to foster long-term thinking; the effects of radiation from nuclear fallout, climate change, and a rise in sea levels will continue to persist for hundreds and thousands of years, and sometimes much longer, even if we were to eliminate their causes tomorrow. Keeping this knowledge in mind may hopefully contribute toward an improved understanding of the concept of time. It could teach us not only to create, implement, and monitor those future prospects that seem most probable – but also those that are possible and desirable.

When will it be decided whether the Anthropocene will be declared – and who makes this decision?

The final decision is made by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), the largest and oldest constituent scientific body in the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) – sometimes jokingly referred to as the UN of geology. The Anthropocene Working Group, which I have been a member of since 2012, presented its proposal to the public on July 11, 2023. This proposal now has to be finalized and formally submitted, at which point it will be voted on by the SQS (Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy), the ICS, and the IUGS.

The success of the proposal is by no means guaranteed. It remains to be seen whether the committees will agree to formalize the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch – at least sixty percent of the bodies involved must vote in favor of the decision. If they do so, then we assume that the Anthropocene will be officially formalized in 2024 at the next International Geological Congress in Busan, Republic of Korea.

Going back to the topic of Crawford Lake in Canada – what does this have to do with the golden spike that your group wishes to place there?

The term “golden spike” was borrowed from a specific chapter in railway history, namely the completion of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States. It was decided to complete the last link in the transcontinental railroad with a spike made of gold. After such a difficult construction process, the spike was a celebration of the railroad’s completion. The Golden Spike National Historic Park commemorates this event.

As “Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, geologists have taken to calling the marker a “golden spike.” Formally declared epochs are included in the ICS’ International Chronostratigraphic Chart, a diagram that precisely defines specific units on the international geological time scale and acts as a standardization tool for all work concerning the stratigraphic history of the Earth.

The process of getting a new unit in the history of the Earth formalized can be long and arduous, which is why the moment at which the “golden spike” is officially driven into the geologic boundary is real cause for celebration. I am very much looking forward to the moment at which we can officially mark the Anthropocene.

Christine Boldt conducted the interview.