Three Questions about Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka died on June 3, 1924. His themes are timely today, but there are still many open questions about his work.

May 21, 2024

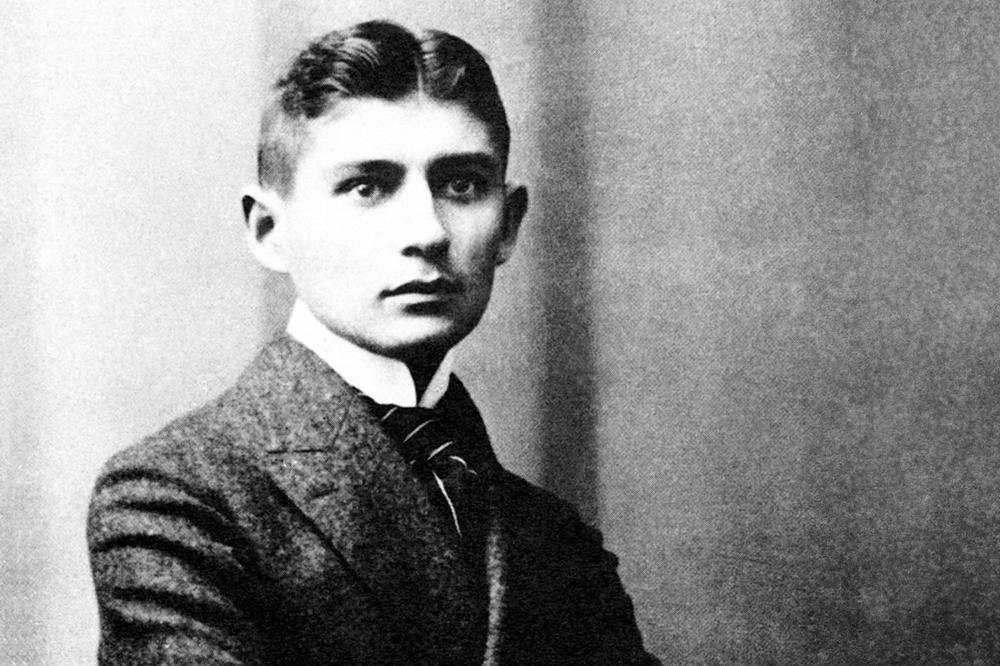

Franz Kafka: The themes in his novels, short stories, and drawings are modern and timely.

Image Credit: picture-alliance-CPA-Media-Co-Ltd

We asked three Kafka enthusiasts for their stances on three questions: Literary scholar Cornelia Ortlieb, illustrator Merle Stanko, and Kafka biographer Peter-André Alt.

1. “Classical writers are authors whose names everyone knows without necessarily having read anything by them” – this quote is from an interview with Peter-André Alt. Is Kafka (also) a classical writer in this sense?

Peter-André Alt is a literary scholar at Freie Universität Berlin, where he served as president of the university from 2010 to 2018. He has been a member of the management board of the Wübben Wissenschaftsstiftung foundation since 2023.

Image Credit: David Ausserhofer

Peter-André Alt: According to the historical aspects that guide my definition, Kafka is a classical writer. However, that is not the case if we look at the criteria that determine stylistic traditions and intellectual history, which insist that literature present a harmony of form and humanistic messages to be classified as classical. In this vein, stories in which fathers sentence their children to death, traveling salesmen turn into beetles, execution machines and anonymous court systems torment people, and legal systems appear as labyrinths cannot be classics. Accordingly, Kafka’s literary realm, which consists of deceptions, deceit, and double meaning, is no more classical than our fears or dreams that appear again and again to unsettle us.

Cornelia Ortlieb: Kafka’s texts are timeless, and in this (classical) sense they are classics. At the same time his name is a cipher for a modernity in which we are astonished to recognize our own times. Flying machines, cinema films, machines that transmit voices, and technical equipment that produces writing appear in his stories as a matter of course right along with seemingly archaic hybrid creatures. Animals and all kinds of things seem to lead a strange life of their own. Everything sits, everything rests, everything moves in a language that has no equal, even where it alludes to the old myth of language confusion, in a single, profound sentence, “We are digging the pit of Babel.”

Merle Stanko: Kafka and his works are literary classics, (also) in this sense. Duden, the standard dictionary of High German language, actually has an entry including his name in the adjective Kafkaesque, to denote something that is “threatening” and incomprehensible. As a classical writer, Kafka can hardly escape being deemed Kafkaesque. It is a shame if an audience knows his name but not his texts because Kafka and his texts can do more than unreliable storytelling in threatening scenarios. One tends to forget that besides being written by a pensive brooder, his texts are often funny. You can read and enjoy them for their humorous aspects.

Merle Stanko is an illustrator. She studied literature at Freie Universität Berlin. In 2015 she published a graphic novel based on Franz Kafka’s story, “Ein Bericht für eine Akademie” (“A Report to an Academy”).

Image Credit: Personal collection

2. Kafka’s stories, which are fabulous in a literal sense, also invite translation into images such as on television, in film, or on stage. Merle Stanko translated the famous story“Bericht an eine Akademie” (“Report to an Academy”) into a graphic novel. Do images make it easier to unravel Kafka, who also expressed himself through drawings?

Merle Stanko: No author and no text will ever be able to be completely unraveled. Every work that was created individually will also be read individually. Comic adaptations of Kafka’s works are completely new works with new contents. Their images are a means of expression to aid in creating meaning and decoding what is read. A good adaptation of Kafka does not clarify the text, but rather plays with its ambiguity and may even create more mystery. Curious readers form their own opinions based on their own experiences in reading and in life.

Peter-André Alt: Kafka developed his texts from the vast arsenal of the unconscious. The systems of power, the spheres of guilt and punishment, the social configurations that he presents to us are all psychologically structured in the end. Mental orders become visible through closed spaces and bodies, open landscapes and animal figures, groups of people, gestures, and physiognomies – the ciphers for power and powerlessness. Anyone who seeks to visualize Kafka’s epic worlds in images or films translates them into another medium without, however, explaining them. Similar to Kafka’s own drawings, the new images or films make a formidable world visible, but they do not make it appear less erratic.

Cornelia Ortlieb: Kafka also drew when he wrote. His letters and notes are illustrated with sketches, individual letters are decorated in calligraphy, the edges of pages are adorned with ornaments. Being able to look at all the drawings in a significant new book is a strange, new experience, to a certain extent intimate and touching. The many portraits also indirectly reveal the artist himself; the many ironically reduced ink stick figures are literally only excerpts. Kafka’s linguistic images remain poignantly mysterious, such as the “telephone earpieces” in which his dream self hears nothing but “a sad, powerful, wordless song and the sound of the sea.” [This is also a play on words because the German word he used for “telephone earpieces” contains the word “Hörmuschel” or “listening seashell.”]

Professor Cornelia Ortlieb teaches literary studies at Freie Universität Berlin. Her main research interests include Berlin modernity.

Image Credit: Georg Pöhlein

3. “Exiles of Love, New Languages, Small Women, and Their Role Models. Kafka’s Berlin” is the title of a lecture Cornelia Ortlieb gave last year as part of a lecture series on “Berlin during the Crisis Year 1923: Parallel Worlds in Literature, Academia, and Art.” Where can we find Kafka’s Berlin in present-day Berlin?

Cornelia Ortlieb: We could go to Tucholsky Strasse to discover traces of the University for the Academic Study of Judaism, which Kafka in 1923 designated as “a place of peace in wild Berlin.” We could use Hans-Gerd Koch’s indispensable book Kafka in Berlin to search for Felice Bauer’s and Kafka’s apartments and to remind ourselves of his happiness with Dora Diamant. In Kafka’s own writings we can recognize our Berlin as a location of longing that promises freedom and a different life, not only for emigrants. Kafka’s stories about Berlin also deal with existential worries and threats in times of crisis. With wisdom and wit, the stories “Der Bau” (“The Building”) and “Eine kleine Frau” ( “The Little Woman”) provide timeless interior views of precarious existence.

Merle Stanko: If we assume that Berlin represented a fresh beginning for Kafka, for “a completely different life,” we can find examples of this everywhere in present-day Berlin. It is a city that can stand for freedom, for inspiration, and for artistry; a city that due to its abundance of offerings can offer a great deal of space for discovery for those who seek it. At the end of the day, one might still find oneself, like Kafka, cramped in a small rented apartment, lying on a desk or staring thoughtfully into the courtyard – on the threshold of actually being.

Peter-André Alt: The Askanischer Hof hotel, where Kafka stayed when he visited his fiancée Felice Bauer in Berlin, was on Königgrätzer Strasse 21. It was there that on July 12, 1914, the two of them conducted an agonizing conversation, which led to their separation. In his diary Kafka described it as “court in the hotel,” and it proved to function as a seed for his novel The Trial. Today the address is Stresemann Strasse 111, and there is no longer a hotel, but rather a modern office building with numerous floors at the location. The tenants include an insurance company. I like to think the publicity-shy insurance lawyer Franz Kafka would appreciate this random sign of a reminder of him because it is not apparent to everyone at first glance.

Christine Boldt conducted the interview. It originally appeared in German in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.