Just across the Border

Literary scholar Jan Konst deals with World War II as a theme in Dutch literature.

Jun 04, 2020

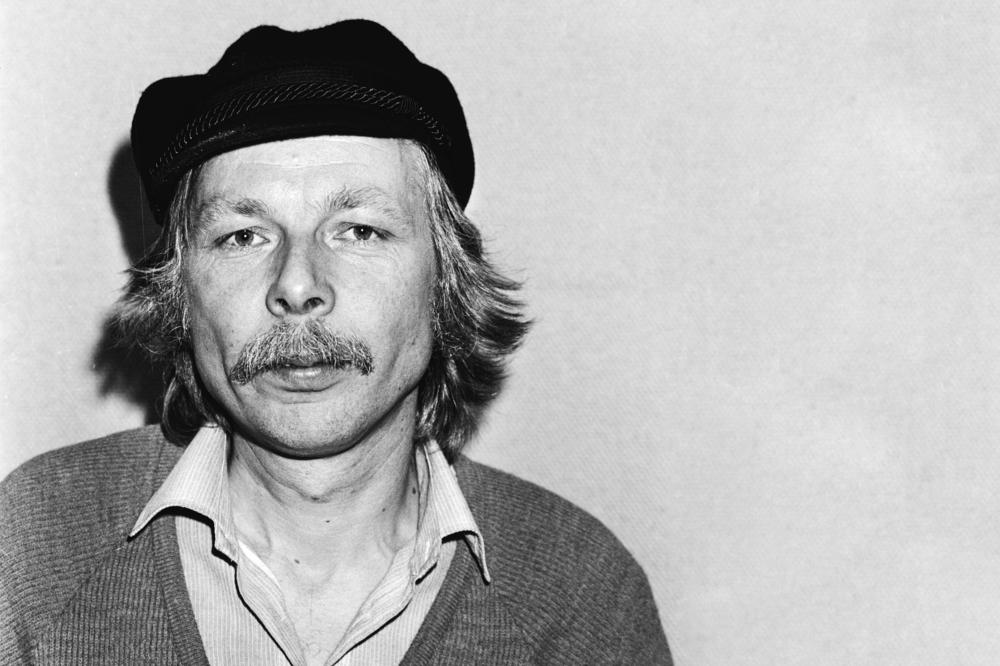

Louis Ferron was a Dutch novelist and poet who wrote during the second half of the 20th century. His work is studied at the Institute of German and Dutch Languages and Literatures at Freie Universität Berlin.

Image Credit: Hans van Dijk - Anefo - Nationaal Archief - CC0

It was during the period shortly after World War II, and Louis Ferron had a difficult time in the Netherlands as the illegitimate son of a German Wehrmacht soldier and a Dutch mother. Other children were not allowed to play with him, and at school he was insulted and excluded. He didn't know where he was really at home. Did he belong to his mother's country or to Germany, where he had spent the first years of his life during World War II? Louis Ferron became a writer. He wrote books in Dutch and won many literary awards. In his novels he dealt with an issue that had a decisive influence on his life: How did the so-called Third Reich come about?

“Unfortunately, his novels were not translated,” says Professor Jan Konst, who works at the Institute of German and Dutch Languages and Literatures at Freie Universität. For years Professor Konst has been doing research on the Dutch perspective of World War II. He has written many journal articles and a book (Alles Waan. Louis Ferron en het Derde Rijk; [Everything Delusion. Louis Ferron and the Third Reich]) about Louis Ferron.

Tone Too Provocative for Publishers?

In the 1970s, Louis Ferron tried to find a German publisher on his own, but his attempts were met wih rejections. Professor Konst thinks the publishers may have been put off by the provocative tone of the books. In his texts, Louis Ferron dealt with topics such as perpetrators and the role of victim, as well as individual responsibility. The novel De keisnijder von Fichtenwald (The Skull Drill of Fichtenwald), published in 1976, takes place in a fictional concentration camp and is told from the perspective of an SS man.

According to Konst, Ferron's work is an example of how varied World War II has been dealt with in Holland, Germany's neighboring country. “Just like in Germany, World War II was the most important topic in Dutch literature for several decades after 1945,” says Jan Konst. An anti-German tone prevailed for a long time. Germany has only been perceived more positively in the Netherlands and no longer associated exclusively with World War II since the 1990s. It took that long for the Dutch to observe that Germany had developed into a stable democracy.

A New View of World War II

Present-day young Dutch writers have a completely different view of World War II, and their writing reflects this. For example, the Dutch writer Mano Bouzamour whose parents were born in Morocco published a bestseller in 2016 De belofte van Pisa (The Promise of Pisa), in which he had Anne Frank, who was murdered in Bergen-Belsen, survive the Holocaust and track down her tormentors. “For older generations, of course, this would be a taboo,” says Jan Konst.

For Konst German history has played a major role in recent years not only for him as a literary scholar, but also in his private life. In the narrative nonfiction book Der Wintergarten. Eine deutsche Familie im langen 20. Jahrhundert (The Winter Garden. A German Family in the Long 20th Century), he told the story of his wife's Saxon family over 150 years. He was inspired to do so by his mother-in-law, who kept showing him the extensive family archive: photo albums, certificates, invoices, business books, postcards. Hilde, born in 1902, is one of the main characters in the book; she experienced the Empire, Weimar Republic, Third Reich, GDR, and reunification. She died in 2001. “I could have told my children: I am Dutch; I am keeping out of your German history,” says Jan Konst. “But I feel like a European, and I am interested in our common past.”

Understanding Doesn't Mean Sympathizing

Even if the family was a rather apolitical “average family,” when it came to evaluating the sources, Konst carefully examined the moral questions that affected him as a Dutchman. For example, he read the diary of his wife's grandfather, who was a Wehrmacht soldier in the Netherlands.

“I realized once again that there is a large gray area between good and bad,” says Konst. “I can understand a lot of things better now, which doesn't mean that I have to sympathize with everything.” His experience as a literary scholar helped greatly when he was evaluating the sources. “It is always important for me to pass on my knowledge to others,” says Jan Konst. “I would like to reach a broader audience, to practice a kind of applied humanities.”

Literary scholar Konst will be speaking to his students about World War II this semester. He is teaching a seminar on the literary processing of the bombing of German cities with a focus on the prolific Dutch writer Harry Mulisch whose novel Het stenen bruidsbed (The Stone Bridal Bed), published in 1959, was also published a year later in German. It is about a former American bomber pilot who was involved in the destruction of Dresden and returned years later. The seminar will take place in digital form due to the coronavirus pandemic.

This text originally appeared in German on April 26, 2020, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität.