A Systematic Approach to Technology

Artificial intelligence is viewed and used differently in China, the United States, and Europe. Researchers from Freie Universität Berlin are studying how this affects each of these societies.

Jan 07, 2020

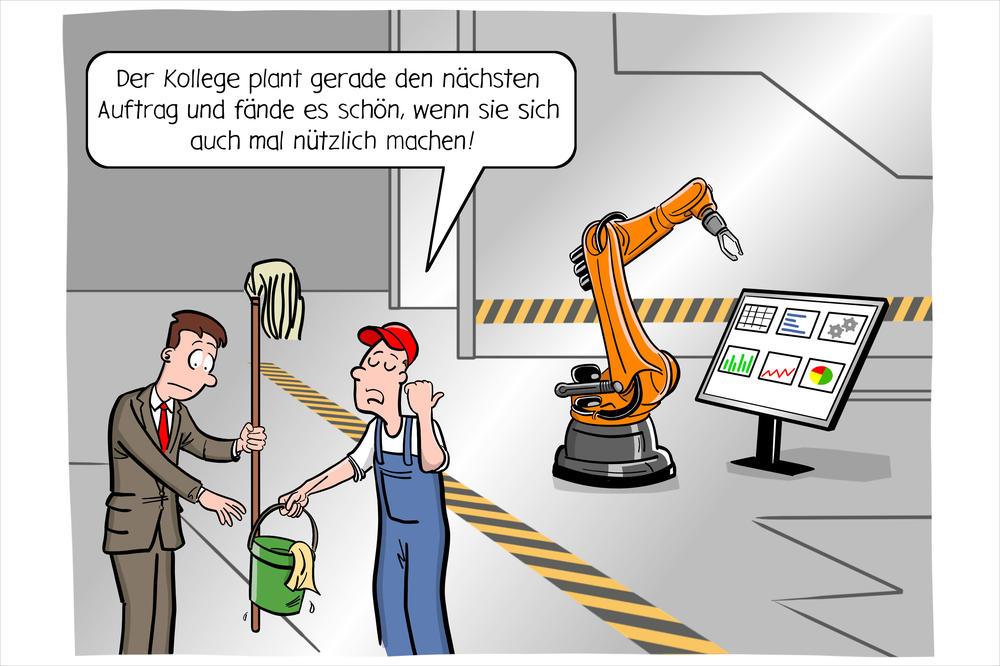

“The new guy is planning the next order and asked if you could pitch in and make yourself useful.”

Image Credit: picture-alliance / DIEKleinert.de / Christian-Möll

Robots that replace people on the job, destroy their privacy, monitor everything, and eventually come to rule the whole world: These days, these kinds of sci-fi dystopias seem more plausible than ever. Some people even liken the development of artificial intelligence to seismic shifts like the Industrial Revolution, in the 19th century.

But technologies are not inherently good or evil in themselves. Whether they spark progress in society or lead to a dystopian situation depends on people: developers and users. That’s what Genia Kostka and Sabrina Habich-Sobiegalla, two professors of Chinese studies at Freie Universität, assume. They are the initiators of the research project titled “Government-Business Relationships in the Area of Artificial Intelligence and How They Affect Society,” which has received a one-year planning grant from the Volkswagen Foundation.

The scholars plan to study how the role of the state and the business sector in China differs from that seen in Europe and the United States. Their hypothesis is that because artificial intelligence is studied, used, and viewed differently in these three regions, the effects on each society also vary.

The two Chinese studies scholars from Berlin put together an international team of scholars from various places, from Johns Hopkins University, in the United States, to institutions in Berlin and Singapore and Peking University, in China, that brings together social sciences and technical sciences. If the foundation finds the research concept persuasive, up to 1.5 million euros will be available starting in the coming year for thorough study of the topic.

“To develop artificial intelligence, companies have to have access to data and be able to structure them appropriately,” Habich-Sobiegalla says. And that applies first and foremost to the technologies we already encounter today. When Netflix “knows” what movies we will like, Facebook “guesses” who appears in our travel photos, and computers control how much product inventory is supposed to be in stock at Amazon warehouses, the basis is always machine learning: algorithms improve themselves without a human writing the code. This form of artificial intelligence is successful in the United States and China, where major conglomerates collect data and laws permit experimentation with those data.

But there are other sub-fields of artificial intelligence as well. “When people dream about robots that speak and act like humans, they aren’t thinking of machine learning,” says Jesse Lehrke, who holds a doctorate in political science and came to Freie Universität to work on the research concept. “The material for science fiction is found in the Human Brain Project.”

This project is a flagship among the research projects financed by the European Union. In it, more than 130 research institutions are working together to simulate the human brain. The project could be a milestone on the road to a robot that is indistinguishable from a human. However, this field is still uninteresting to the private business sector, which means it has to rely on government support.

China, too, wants to be a leader in research in this field, but with a different approach. “The state selects successful companies, supplies them with a lot of money, and tells them which field they are supposed to be ‘champions’ in,” says Habich-Sobiegalla. “In Germany and the U.S., by contrast, the market is regulated by law, not by direct interventions.” In China, the state’s interest in controlling society is the dominant factor, she explains. Not least because an organizational unit of the communist party is required to be incorporated into every company’s structure. And when it comes to national security, companies have to give the one-party state access. “Anything can be declared a matter of national security,” she says.

Chinese state capitalism, the American free market economy, and European regulation following a precautionary approach: Technologies and their use are often perceived very differently across these three systems. Automatic facial recognition is one example. “In some cities in China, it is already helping the police to punish people within 15 minutes if they cross the street when the light is red,” Habich-Sobiegalla says.

While this level of surveillance is viewed positively in China, as a gain in terms of safety, Western observers tend to see it as a threat to freedom. The use of facial recognition was recently banned in San Francisco, for example. “In Europe, most companies wouldn’t even think about developing technologies like this, because they know the state would not allow them to be used,” says Habich-Sobiegalla. There’s no stopping advances in technology, she points out, but governments do have more of an influence on how these developments change society than many decision makers are aware.

This text originally appeared in German on December 7, 2019, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität.