Possible Remnant of Colonial Injustice

A biology student investigated the provenance of human remains in a teaching collection and urges more awareness of and further research on the origins of such collections

May 08, 2023

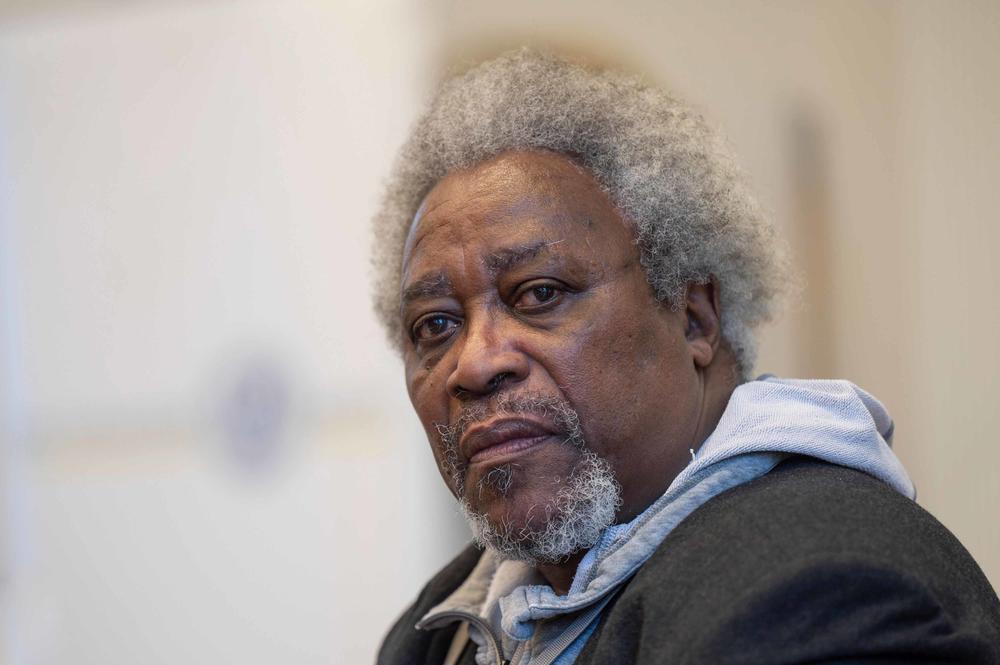

Mnyaka Sururu Mboro is a human rights activist and co-founder of the nongovernmental organization “Berlin Postkolonial.”

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Human remains were once a popular teaching aid at universities. Freie Universität Berlin is no exception to this; its zoological collection at the Institute of Biology contains human remains whose origins are unclear. But where are they from? Is it ethical to keep them there and allow students to handle them in class?

Katja Nowick, a professor of human biology, said members of a working group set up to investigate the provenance of human remains in a teaching collection discussed these issues extensively. In November 2021, master’s student and human biology instructor Vanessa Hava Schulmann began checking the origins of the human remains in the zoological collection of Freie Universität Berlin’s Institute of Biology. She was supported in this research endeavor by the department’s human biology teaching staff, including Dr. Vladimir Bajić, Dr. Vladimir Jovanović, and Anne Hartleib. During the research, Schulmann documented approximately twenty human skulls, as well as additional human remains such as jawbones, teeth, long bones, foot bones, hand bones, several almost complete human skeletons, and various other human anatomical specimens. However, she found little information on the provenance of these remains.

Using Human Remains Requires Informed Consent

Katja Nowick is a professor of human biology at the Institute of Biology at Freie Universität Berlin. For teaching purposes she and her team no longer work with human remains, but rather, solely with models of human bones.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Following today’s standards, using human remains for scientific and medical purposes requires documentation of informed consent. Novick points out that nowadays members of the teaching staff work with models and discuss the ethical aspects with students in their classes. Schulmann notes that with regard to such collections, there is a real possibility that human remains may originate from colonial injustice. “The history of science in Berlin must always be viewed in connection with colonialism and National Socialism. Both were still a major influence in the 1950s, when the collections at Freie Universität were being compiled,” she says.

This was also confirmed in a scientific report commissioned by the Berlin Senate and the organization Decolonize Berlin e. V. to investigate human remains from colonial contexts. Presented by provenance researcher Isabelle Reimann, the report was the first cross-institutional inventory. It recommended further provenance research in the zoological teaching collection as well as a cross-institutional review.

Two Human Remains from the Luschan Collection

Biology student Vanessa Hava Schulmann is hoping that the project will spark a discussion about scientific and social responsibility in research and teaching.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

The report confirmed that two human bones, a humerus and a mandibula, at the Institute of Biology, Freie Universität Berlin, stem from a colonial injustice context. The team had consulted provenance researcher and anatomy professor Andreas Winkelmann from the Brandenburg Medical School for his expertise. He drew attention to the possibility that these human remains could once have been part of the Luschan Collection, which was compiled by physician and anthropologist Felix von Luschan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde (Royal Museum of Ethnology). The collection was then distributed among several universities in Berlin in 1925.

A large part of the collection came from German colonies in Africa and the Pacific region and was once used for inhumane racial research. These human remains were handed over to the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte (Museum of Prehistory and Early History), an institution that falls under the umbrella of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), in July 2022, where provenance research is being carried out on the other human remains from the Luschan Collection.

Mnyaka Sururu Mboro Is Searching for the Skull of Prince Mangi Meli

A public event was held recently at Freie Universität Berlin’s Institute of Biology to provide more information and a platform for discussing the findings of the project. Speakers at the event included anthropologist and provenance researcher Isabelle Reimann from Humboldt-Universität Berlin and Mnyaka Sururu Mboro, human rights activist and co-founder of the nongovernmental organization “Berlin Postkolonial” and board member of “Decolonize Berlin,” two organizations committed to the recognition and reappraisal of colonial injustice. Both speakers had evaluated the collection for the above-mentioned report on human remains from colonial contexts in Berlin collections.

Born in Tanzania, Mnyaka Sururu Mboro works to ensure that human remains and stolen cultural objects are returned to their countries of origin. When he was a child, his grandmother told him about Prince Mangi Meli, who had fought against German colonizers and was beheaded. The colonizers sent his head to Germany. Like many other fighters, the prince could not be buried as required by tradition. When Mboro went to Germany to study engineering, his grandmother made him promise to bring the folk hero’s skull back to Tanzania. He has not found it yet, in spite of having made DNA comparisons in collections he had access to.

Provenance Research Encourages a Debate on Responsibility

For Isabelle Reimann the whole issue is connected to how science sees itself. The history of science is often presented as a series of successes. “In our report it became apparent that there is a great need for provenance research with regard to the history of collections. Coming to terms with the historical interweaving of colonization and scientific racism must go hand in hand with critical self-reflection and accepting responsibility,” says the anthropologist. It is crucial to consult descendants and organizations in the countries of origin in order to clarify how to further deal with objects linked to colonial injustice. These individuals and organizations should be involved in all the steps surrounding provenance research and the return of the remains, as well as forms of remembrance and commemoration in Germany.

Biology student Vanessa Hava Schulmann is hoping that the project will spark a discussion about scientific and social responsibility in research and teaching. She is appealing to policy makers in science and research to allocate more money to provenance research in order to guarantee funding for further projects. The working group has applied for financial support to continue their provenance research as part of a research project.

The original German version of this article appeared in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.