Nameless Poets?

As part of an exhibit in the Philological Library at Freie Universität, students are examining whether stories could have reached Europe as colonial loot

Jun 21, 2023

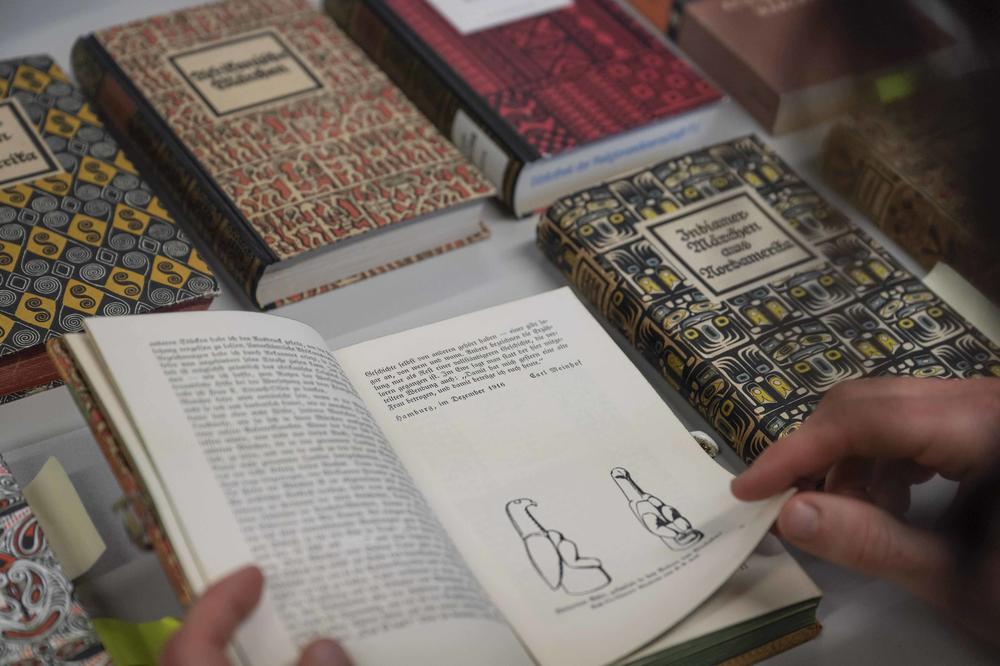

Stories as looted cultural property? Students at Freie Universität are examining literature.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Africa was fashionable among the avant-garde writers. Around 1916 in the Dada bar Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, masked dances “based on motifs from the Sudan” were on the program. Around the same time Hugo Ball wanted to “drum literature to the ground with African rhythms,” and Tristan Tzara searched through ethnological literature about Africa in Zurich’s libraries looking for “authentic” songs and poems. He published a selection of them in the Dada Almanac in 1920.

Outside the Zurich Dada community, the writer and art historian Carl Einstein published the collection Afrikanische Legenden (African Legends, 1925). In 1916 the self-proclaimed Africanist Carl Meinhof published a volume of African fairy tales in the popular book series Märchen der primitiven Völker (Fairy Tales of Primitive Peoples) published by Diederichs Verlag. In France an anthology by Blaise Cendrars caused a stir.

For their translations into German and their adaptations, Carl Einstein and his fellow poets drew on material collected locally by missionaries, linguists, anthropologists, and colonial officials. Einstein listed 141 sources, but he did not provide details about the history of transmission. As a rule he only assigned the texts to general ethnic groups rather than giving more specific information, such as an author’s name.

Volumes that are still sold in large numbers today, such as Die schönsten Märchen aus Afrika (Reclam 2021) in turn cite Carl Einstein and his colleagues as the source of the texts used. Lynh Nguyen, a student who worked on the exhibit “Literature as Colonial Loot?” points out, “No one asked where the texts came from, who told them, or who wrote them down and under what circumstances.” She says that the actual authors remain anonymous. In the blurb of Meinhof’s volume they are designated as “nameless poets.”

Generally, when people speak of colonial loot today, they mean “things”: boats and bronzes, objects from everyday life as well as ceremonial life. However, could stories also have reached Europe as colonial loot?

This question is raised in an exhibit created by students that opened on April 26 in the Philological Library of Freie Universität. Irene Albers, a professor at the Peter Szondi Institute of Freie Universität, says, “We oppose the anonymity of the supposedly ‘nameless poets’ and the decontextualization of the stories.” She cotaught the the research seminar “Looted Literature?” with her colleague Andreas Schmid; the exhibit was created as part of the seminar.

The material on display – first editions, reproductions of source texts, and phonogram cylinders – illustrates how writers of the European avant-garde appropriated texts from the African colonies. Photos and documents, for example from the Blaise Cendrars estate in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern and the archive of the Diederichs Verlag in Jena, make the colonial contexts visible.

Schmid says that the recordings often took place within a relationship of power, and they often occurred under coercion and violence. An example of this practice can be found in a note by Karl Weule, who recorded native chants on wax cylinders in the German colonies. In 1908 he wrote with regard to the East African singer Sulila, “Recently I have been grabbing the blind singer by the collar (…). Then I hold his woolly head as in a vice until the bard has completed shouting his heroic song. I hold on to him, no matter how hard he jerks and tugs and tries to turn his head.”

Some sources do provide names and details. The narrators were usually pupils at mission stations and “native language assistants” at colonial institutes or prisoners. The songs and texts that were collected as “language samples” were usually published in grammar books or linguistic journals. According to Albers, the names and sources were omitted in the transcripts and translations prepared by Tzara, Einstein, Cendrars, and others.

The latter changed the songs and stories as they saw fit, adapting them to their preconceived ideas about “primitive” poetry. Schmid, however, explains that the anthropological sources already had the same tendency to distort the meaning. For this reason, he says that even first-time transcriptions, for example by Leo Frobenius and Carl Meinhof, should not be taken for authentic originals.

It is often not possible to reconstruct the exact chain of transmission of the texts. Vincent Sauer, a student of comparative literature, explains that in most cases clues to the provenance fade away and open questions remain. However, he gives an example of a text whose origin he succeeded in reconstructing. It is a story called “Der Wind” (The Wind) in a collection of fairy tales compiled for children and published in 1928. The German translation is still in print. Sauer’s analysis of its provenance follows below.

The Franco-Swiss writer Blaise Cendrars copied the story from a 1903 anthology compiled by the French Orientalist René Basset without citing any source. Basset in turn had taken it from an English-language journal on South African folklore poetry published in 1880. There the narrator is named: |Han‡kass’o. Photographs of prisoners from the 1870s show |Han‡kass’o as a young man with a serious face. In 1869 he was sentenced to two years of hard labor for stealing sheep. In 1877 his wife and youngest child died following a brutal police attack. For two years, from 1878 to 1879, he lived with the linguists Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd in Cape Town. He was well known as an excellent storyteller, and much of the material compiled by Bleek and Lloyd came from him. |Han‡kass’o thus provided insights into the ways of thinking and the living conditions of the South African people |Xam.

By 1870 encroaching colonization had deprived the |Xam of most of their land as well as their independence. They often resisted, and many of them died in the process. The survivors were forced to work for white settlers and adapt their living conditions. Their language fell into oblivion, and today no one speaks it anymore.

|Han‡-kass’o’s father-in-law, who was called ||Kábbo, wistfully contemplated his home and previous life. He said, “My people liked to visit each other in their huts. They would sit in front of them and smoke together. That is how they learned stories at home.” ||Kábbo also said, “A story is like the wind. It comes from far away, and we can feel it.” Provenance research conducted within the field of literary studies can contribute to expanding how people think of literature itself.

Can intangible cultural assets ever be returned?

One of the nine exhibition showcases is dedicated to issues of restitution. Physical objects can be returned. But is it possible to return intangible cultural assets? So far, there have been few attempts to restitute stories. One example is the Belgian project SHARE. In 2021 4,000 historical sound recordings of songs were returned to the Rwanda Cultural Heritage Academy – on a hard drive.

Schmid concludes, “It is important to liberate the texts and recordings from their predominantly European loop of appropriation and interpretation and to share them.” Understood in this way, restitution above all means collaboration: not a transfer of ownership, but rather a multiplication of perspectives and voices.

This article originally appeared in German in the Tagesspiegel supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.