The Christian Roots of Antisemitism

Theological anti-Judaism and modern antisemitism have been long been understood to be separate phenomena. Rainer Kampling and Sara Han, however, say that they must be examined together.

Mar 15, 2024

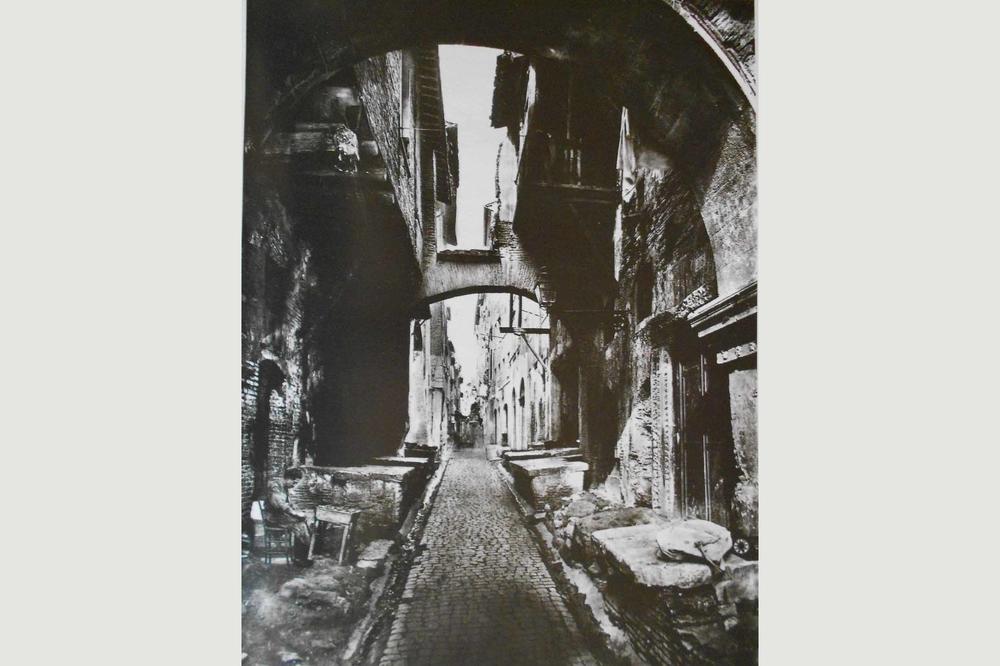

Ostracized and segregated in papal Rome. The Via del Portico d’Ottavia in the Roman Ghetto around 1860. The three-hectare area on the left bank of the Tiber was the last ghetto in western Europe prior to the Nazi period. It was liberated in 1870.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Sconosciut

Antisemitism has long been widespread in Europe. Christian scriptures from late antiquity contain insults and, beginning in the fourth century, calls for violence against Jewish people. These invoked stereotypes and ways of thinking that are circulating to this day. “These range from malicious portrayals of Jewish people as money-hungry, power-driven, and morally deformed,” says Rainer Kampling, “to the baseless accusations that Jewish people were to blame for the death of Jesus, murdered children, and poisoned wells.”

Kampling is a Catholic theologian and Emeritus Professor of Biblical Theology at Freie Universität Berlin. He coordinates the research project “Christian Signatures of Contemporary Antisemitism,” funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Kampling opposes simplistic portrayals in the public discourse, such as Christian anti-Judaism in Germany is an artifact of the past or that religiously based antisemitism is an “import” from Muslim countries. “Antisemitism did not simply disappear from Germany after 1945,” he says. “And contemporary forms of hatred toward Jewish people are not a result of immigration. Up to this day, antisemitism is inscribed deeply in the cultural history of Christianity, and thereby also of Germany.”

Focus on the Present

Three sub-projects in the research project examine the Christian background of antisemitism. One special focus is the relationships to contemporary manifestations. In addition to Freie Universität participants include the Leibniz Institute for Educational Media | Georg Eckert Institute (GEI) and the Protestant Academies in Germany in cooperation with the Selma Stern Center for Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg. “Antisemitism arising from Christian religious motives on the one hand and so-called modern antisemitism arising from racism are often considered to be different streams,” says Sara Han. “However, they cannot actually be separated.”

Han is a Jewish studies scholar and Catholic theologian and is looking in particular at continuities in both East and West Germany as part of the research project. “There were church initiatives both in the GDR and the FRG that sought to enter into dialogue with Jewish people after the Shoah,” she says. “For a long time, the church considered that this was all that needed to be done.”

From Distancing to Targeting

However, it is clear that antisemitic ways of thinking rooted in an anti-Jewish theology have been widespread in society and still are to the present day. “Such views can be quite clearly seen in the connections between New Right groups and groups that consider themselves to be Christian and are also politically active, and they both refer explicitly to Christian traditions,” says Han. “But antisemitic views could also be heard in the context of the so-called ‘Querdenker’ movement during the coronavirus pandemic. And again now, since the outbreak of war in Israel and Gaza.”

Kampling places the origins of theological antisemitism at the beginnings of what would go on to become Christianity. This was a religious-sociological phenomenon in a minority group. “Around the year 50, there was an extremely small group of baptized people who understood themselves as primarily Jewish,” he says. “By contrast, Judaism was widespread in the Roman sphere of influence, and its common center was the Jerusalem Temple.”

There were often no clear dividing lines between the two communities of faith. Even in the subsequent centuries, people had doubts about whether there were fundamental differences in Christian and Jewish religious practices. “There were many people at that time that considered themselves as belonging to both groups,” says Kampling. “Jewish people that wanted baptism, and Christians who wanted circumcision.” But the early Christian theologians feared that these kinds of examples could endanger the small Christian community. This is why they made targeted attempts to drive a wedge between both groups. “The consolidation of the Christian community,” says Kampling, “was about strengthening its own identity as group by distancing themselves from and devaluing the others.”

The attempt at distancing was, however, full of theological difficulties from the very beginning. “The first Christians wanted to be different from all the others. At the same time, their faith was deeply dependent on the Jewish scriptures, which they believed to have an exclusive claim to interpret.” The new Christian faith could not exist without the Old Testament. “And this dependence is the sore spot of Christian anti-Judaism,” says the theologian.

This interplay between distancing and dependency spawned the hatred that persisted throughout many centuries of Christian history. The plague years between 1347 and 1353 were crucially important for Christian European antisemitism. Throughout Europe, Jewish people were blamed for deaths due to plague, and were accused of poisoning wells. There were severe pogroms. Entire Jewish communities were obliterated, frequently with the approval of Christian priests. “During the plague, Jewish people were branded and persecuted as cunning conspirators with murderous desires,” says Kampling. “It was the birth of conspiracy theories just as those we see today as well.”

Antisemitic Statements

For a statement to be considered antisemitic, it does not have to explicitly mention Jewish people, says Han. “Conspiracy theories often revolve around the concept that there are mysterious powerful people that control everything behind the scenes. And there are quite a number of people for whom these people were and are ‘the’ Jewish people, even if the code word ‘elites’ is used instead.”

A second mechanism of antisemitism is collectivization. “We see this clearly today in the conflict about the war in Israel and Gaza,” says Han. “In this context, ‘the Jewish people’ are made collectively responsible for the actions of the Israeli government. Such arguments are motivated by antisemitism.”

Rainer Kampling and Sara Han are seriously concerned about the current developments in Germany. At Freie Universität as well, many Jewish students have felt highly uneasy and threatened in the past months. Kampling therefore applauds the opportunity for people who experience or observe antisemitism on campus to turn to a contact person: “This person of trust provides confidential one-on-one advice about strategies for all people affected by antisemitism,” he says. “Antisemitism is a widespread societal problem that we must face together.”

This article originally appeared in German in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.