Discovering Lost Texts

Scholars from the United States, Europe, Africa, India, and the Middle East attended a conference at Freie Universität, where they discussed the long-overlooked history of Arabic-language text practice.

Oct 06, 2017

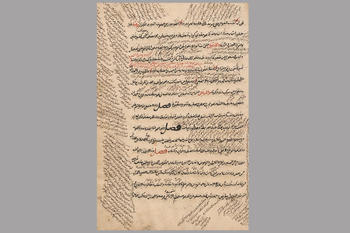

A wealth of comments: The original of this Arabic manuscript by philologist az-Zamaḫšarī dates to the 12th century, while the copy shown with comments is from 1546.

Image Credit: SPKB Fotostelle

The journal "Philological Encounters" has been published semiannually since 2016.

Image Credit: Peter Schraeder

Junior professor Dr. Islam Dayeh organized an international conference entitled “What was Philology in Arabic? Arabic-Islamic Textual Practices in the Early Modern World.”

Image Credit: Peter Schraeder

Arabic is a global language: It is written and spoken from West Africa through the Middle East and even some parts of India, and has been for centuries. But the tradition of preserving and interpreting Arabic texts was abruptly interrupted with the start of the colonial era in the 19thcentury.

From then on, it was Western philologists who determined how Arabic texts were handled. Islam Dayeh, a junior professor at the Institute for Semitic and Arabic Studies at Freie Universität, wishes to rediscover Arabic text practices and illuminate them from a wide variety of perspectives. To this end, he recently organized an international conference to find out what early Arabic philology was like.

Journal of Critical Philology

Dayeh heads both a research group named “Arabic Philology and Textual Practices in the Early Modern Period” and the Zukunftsphilologie research program at Freie Universität, which was jointly initiated with Forum Transregionale Studien. The goal of both research projects is to go beyond the classical Greek and Latin canon of text research and investigate text cultures from all over the world.

At the conference Dayeh presented a new journal, launched in 2016, entitled Philological Encounters. It is dedicated to the creation and dissemination of texts and their philosophical and theoretical content alike. The journal is published twice a year, both in print and as an online version.

“Wherever there were texts, there was also a method of uncovering what they meant,” Dayeh explains. He says that Arabic was to the Islamic world as Latin was to Christian Europe. “Latin and Arabic strongly influenced each other,” Dayeh explains. This is highlighted in the second issue of Philological Encounters, which deals with the influence of Arabic texts around the Mediterranean. But this wasn’t the only place that Arabic came into contact with other languages. The first grammatical summaries of the Hebrew, Farsi (Persian), and Turkish languages were written in Arabic.

A Special Kind of Reading

The conference drew participants from the United States, Europe, Africa, India, and the Middle East. During the event, they examined not only different traditions of knowledge in Arabic, but also a wealth of different genres of text. In the Arabic manuscript culture of the pre-colonial era, it was common to write comments and glosses around the original text. This meant that the original was copied, with comments being made in the margins – much like in today’s word processing programs. Further comments, often ironic ones, were added to the original and comments over the centuries.

“Sometimes there are five or six texts on one piece of paper. People read what others had read,” says Dayeh. “The Arabic scholars had a different concept of authorship and originality than the European ones did. They added their voices to those that had come before.” But these “secondary voices” were ignored by most European scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries. They were mainly interested in the original texts, since they referred to the Bible or represented translations of classical Greek and Latin texts. They disregarded the Arabic comments.

Giving Arabic Studies a New Face

As a result Dayeh believes his research also represents a contribution to the history of the humanities. He wants to give Arabic studies “a new face,” as he puts it.

“The conference brought together people who hadn’t previously thought as much about merging global perspectives,” Dayeh explains. To him, things are moving in a clear direction: “We want to rediscover what we have lost.”

This text originally appeared in German in the Campus.leben online magazine published by Freie Universität.