“The Victims Feel They Have Not Been Heard”

Social Scientist Natalija Bašic Is Investigating the Impact of the Trials Conducted at the War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague on People Living in Former Yugoslavia

Feb 22, 2010

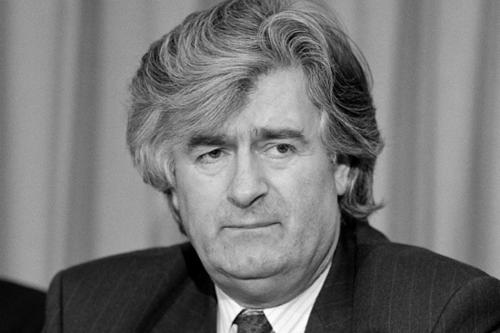

In March the trial of former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić is to be continued.

Image Credit: UN Photo/Milton Grant

There has been peace in the Balkans for 15 years – and yet the story of the war in Bosnia is not over. The “Butcher of Bosnia,” as the former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić has been called, is still in detention pending the investigation of his case. The charges against him include complicity in the deaths of 10,000 people during the siege of the Bosnian city of Sarajevo. His trial in The Hague is scheduled to continue in March. The former Serbian president Slobodan Milošević, who was charged with genocide in the same court, died during the four-year trial. Natalija Bašic is conducting research at Freie Universität on how the tribunal is perceived by residents of former Yugoslavia.

Ms. Bašic, you started a study in Serbia last year, and you have already analyzed your talks with 30 Serbs. What do the respondents in your study think of this kind of war crimes trial?

In terms of the trial of the former Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević, the respondents are ambivalent toward the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. On the one hand, the tribunal itself is criticized, but on the other, people are strongly in favor of the cooperative approach.

What kind of criticism of the tribunal do you hear?

The victims of the regime who were displaced or lost family members feel that they are not adequately represented in court. This is partly because in many cases, the court in The Hague does not need to hear witness testimony because there is other evidence to prove the acts. Some respondents also wonder at the fact that the penalties imposed on a war criminal are no different from those in a typical criminal trial. Because Milošević killed thousands does not mean that his sentence would be a thousand times more severe than that imposed on someone who commits a murder on the streets of Belgrade, Zagreb, or Sarajevo today. That’s hard for some of the respondents to understand.

Why do your respondents consider the trial to be unfair?

The misunderstanding is that the justice system is based on a fundamentally different view of truth than normal people’s understanding of it. A court is not there to discover or explain historical truths. Its role is to take certain materials that can be used in court and use them to arrive at a judgment. The things that a court takes as the basis for its decision are often different from the aspects a historian would consider important. The law, justice, and fairness do not mean exactly the same thing.

Is it only the victims who are unhappy with the trial?

No. Most of the respondents I have interviewed have been very regretful that the trial was not completed because of Milošević’s death. And that is somewhat surprising because the interviews were not conducted in Bosnia or Croatia, but in Serbia.

Milošević used his trial as a public forum right up until his death. How was that received among your respondents?

Because Milošević defended himself in court and the trial was broadcast on live TV, he was able to manipulate people even far away from his homeland. Several of my respondents have stated that although they were initially strongly opposed to Milošević, they suddenly took his side. It’s like a soccer game, with people rooting for one side or the other.

Is it a group phenomenon?

Only in part. The respondents were excited and fascinated by Milošević’s rhetorical skills. Here you have this one figure, standing alone in front of this big, important court and defying it – that impresses people. Afterwards, they are embarrassed and ashamed of their fascination. After his arrest, Karadžić also tried to portray himself as a martyr, telling media representatives that some countries had “used and abused a small country” to achieve their own military and strategic aims. The lack of awareness of how a trial works produces a certain sense of powerlessness. And that in turn leads people to come up with conspiracy theories. They think there is something strange about the court proceedings, or that the trial is being used to legitimize the military intervention in the late 1990s after the fact. That has also been evident from my interviews.

The Croatian writer Edo Popović wrote in Der Spiegel that the Serbs were unwilling to face their past even after Karadžić was arrested. Did you have the same impression?

No. I think that the way the history of the war in Yugoslavia is being processed is much faster than the process in Germany after World War II. On the Internet, the younger generation has access to international media and not just the newspapers that are available to them in their own country. But even there, the censorship is not as severe as is widely believed in Germany. People have a lot of sources of information.

What’s next for your study?

I am planning to return to the region in the spring, this time to Bosnia or Croatia. Once I am there, I will conduct interviews similar to the ones I did in Belgrade, always in groups of six participants. I may even be able to get representatives of different groups to sit down at the same table – Serbs and Croats, for example. We’ll have to see if the willingness is there.

What are your hopes for that kind of meeting?

To get a more nuanced, more sharply delineated picture of how people cope with the experiences of war – and what feelings are involved as they do so.

—Interview: Philipp Eins

Further Information

Dr. Natalija Bašic

Languages of Emotion Cluster of Excellence, Freie Universität Berlin

Tel.: +49 (0)30 838-562 13

Email: natalija.basic@fu-berlin.de