The Nerve Center

How the NeuroCure research alliance draws top scientists to Berlin, and how tricky diseases are decoded there

May 26, 2011

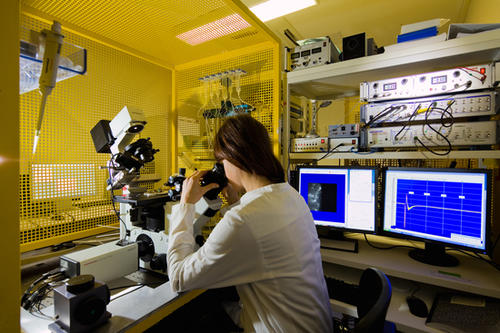

Within the NeuroCure excellence cluster, scientists from various neuroscience disciplines work together.

Image Credit: NeuroCure

The little girl suffered repeatedly from severe strokes. Her parents feared for her life; doctors were puzzled. Markus Schülke, professor of experimental neuropediatrics at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, still recalls his little patient quite clearly: “The cause of the strokes was completely unclear at first,” he says. A child with strokes? There was no explanation.

The little girl suffered repeatedly from severe strokes. Her parents feared for her life; doctors were puzzled. Markus Schülke, professor of experimental neuropediatrics at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, still recalls his little patient quite clearly: “The cause of the strokes was completely unclear at first,” he says.

A child with strokes? It was not until genetic studies were performed that the physician and his colleagues were able to track the problem to its source: A mutation was disrupting the flow of blood in the vessels of the brain. When blood vessels dilate and contract, and how good the circulation in those vessels is afterward, is controlled by a “calcium channel” that regulates the concentration of calcium within the cell. This is where the doctors ultimately found the defect. As a result, they were able to treat the little girl, in what turned out to be a fairly unusual way: Medications that otherwise help patients with heart arrhythmias, but are not actually used to treat strokes, were prescribed. They helped.

“We wouldn’t normally have thought of this approach,” Schülke says, continuing, “It was a highly specific case.” He and his colleagues work and research together in the NeuroCure cluster of excellence, a research alliance hosted by Charité, the joint medical school of Freie Universität and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, which also includes participation by scholars and scientists from a number of institutions not affiliated with either university. The idea behind the cluster is to bring together fundamental researchers and clinicians in order to develop treatments for neurological diseases more quickly and with greater success – not only for strokes, but also for those suffering from multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. The girl’s successful treatment was only possible because at NeuroCure, there are many options that are not typically available in normal clinical practice – such as costly and labor-intensive genetic studies.

NeuroCure is funded as part of the Excellence Initiative jointly sponsored by the German federal government and the governments of the individual German states, receiving about 50 million euros. The money also gives the research alliance a measure of independence: It is the scientists and researchers themselves who decide how to use their resources. Clinical trials are often performed at the initiative of the industry that intends to use the results commercially later on. At NeuroCure, the focus is not always on expensive treatments; researchers also have the freedom to study topics such as how promising green tea extract is from a therapeutic standpoint. The cluster has created a kind of scientific nerve center in Berlin: a network that combines various disciplines, does pioneering work, and has made a name for itself all over the world.

One of the first people to be convinced of the concept behind NeuroCure was Christian Rosenmund. Rosenmund, a professor and neuroscientist, accepted an invitation to work at Charité back in 2009. Before that, he had done research in the United States, studying nerve cells in mouse brains and doing extensive scientific work on how cells communicate with one another via synapses. Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine, one of the world’s most prestigious biomedical centers, had given him a lifetime professorship. In the end, however, he decided to move to Berlin to work at NeuroCure. “For one thing, Germany is where my cultural roots are,” says Rosenmund, who was born in the German city of Hanau and studied pharmacy in Frankfurt. “For another, I was excited about the sense of being on the leading edge of a new development, and about the chance to work together with colleagues at NeuroCure.”

Rosenmund and his team have just succeeded in making another modest breakthrough, one that sounds complicated at first, but which Rosenmund can explain in simple terms: It has to do with the flow of information that comes together in places like the cortex and then needs to be processed by the nerve cells. “You can picture the nerve cells as being like a music fan. He doesn’t hear individual notes, but rather the entire concert,” Rosenmund says. He compares the synapses to individual tones – some are louder, some quieter. Before the team’s work on the subject, scientists did not know how, or through what mechanisms, the volume was controlled, but they did know that improper regulation of the synapses can have devastating effects on signal processing within the brain, even leading ultimately to neurological diseases and disorders. Rosenmund and his team have now been the first to discover what regulates “volume” in nerve cells – the protein endophilin. “Ultimately, we have finally identified a mechanism for how synapses can be controlled differently. The brain is able to adjust the synapses optimally to different brain functions,” Rosenmund says, adding that this may help scientists better understand or even treat neurological diseases such as epilepsy.

Rosenmund himself used to play the violin. The job doesn’t leave him much time for music these days, but he is still grateful to have it: “As a scientist, you don’t want to come to rest. It is a privilege to be able to work this way here, and that society gives us this opportunity.” .Rosenmund plans to contribute his efforts to ensuring that Berlin’s “nerve center” continues to grow.

Further Information

- Prof. Dr. Christian Rosenmund, NeuroCure, Tel.: +49 (0)30 / 450 539 061,

Email: christian.rosenmund@charite.de - Prof. Dr. Markus Schülke-Gerstenfeld, NeuroCure,Tel.: +49 (0)30 / 450 566 468,

Email: markus.schuelke@charite.de