A Shooting Rampage Is Never Spontaneous

Working at Freie Universität, psychologist Rebecca Bondü has analyzed the reasons and risk factors associated with school shootings

Apr 02, 2012

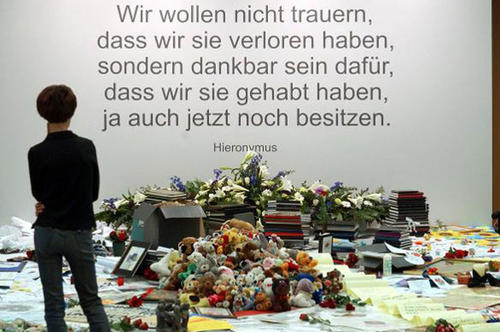

Mememtos placed at a memorial to the victims of the shooting rampage in Erfurt, Germany, ten years ago.

Image Credit: picture alliance

It has been ten years since Robert Steinhäuser, then still a high school student, entered the Gutenberg secondary school in the city of Erfurt with a gun and went on a rampage, killing 16 people, including 12 teachers and two students. Working within the Berlin Leaking Project at Freie Universität Berlin, psychologist Rebecca Bondü has conducted a study of school shootings, including the shooting rampage in Erfurt and many other school massacres. The project is based on the theory that there are always warning signs before an individual goes on a rampage, including verbal threats or fantasies of violence posted on the Internet by the later perpetrator.

In her dissertation, the 32-year-old Bondü analyzed the records kept by public prosecution offices regarding rampages that took place in schools in Germany between 1999 and 2006 in order to flesh out a more complete picture of the perpetrators and investigate whether there had been any signs that might have offered a warning of their intent. “In fact, we can see that there were warning signs in every one of the cases. Not one of the crimes was committed spontaneously,” Bondü says. Although the chain of events and motives for the cases vary, all of the perpetrators gave off clear signs that might have given pause to those in their social environments. “For example, there were verbal announcements, and drawings and texts were created. There were videos and photos that were sent out, in some cases via the Internet.” This kind of activity is known as giving off “direct warning signs.” “Indirect warning signs,” by contrast, are found when a student begins to display a particularly keen interest in school shootings, weapons, and past cases, for instance. “These kinds of warning signs can take many forms, in some cases extending over years. It is important for teachers and other persons of trust to register these signs.”

Nonetheless, Bondü points out that there are no clear-cut criteria for identifying a potential school shooter, cautioning against blanket judgments – especially now, on the tenth anniversary of the Erfurt attack. Above all, Bondü says, we cannot assume that there is only one motive driving a person to commit this kind of attack. In most cases, there are multiple causative factors, which, she urges, should also be taken into account in work toward prevention. Banning aggressive computer games and tightening gun control laws are important steps to take in enhancing people’s subjective sense of security, but they alone have too little effect, leaving the root cause of rampages untouched.

But what is the root cause? An initial explanation begins to emerge when the school shootings that have occurred in Germany are compared with those in the United States, where two-thirds of all of the incidents registered worldwide have occurred. Bondü looked at this aspect in her dissertation and found that the school attacks that have occurred in the U.S. in the past were mainly aimed at fellow students. Bullying among students could, therefore, be one of the reasons that those who commit rampages in America choose students as their primary victims. In Germany, by contrast, teachers have been the perpetrators’ main targets. It also turns out that many of the German perpetrators were former students who returned to their old schools to carry out their shooting sprees, before then committing suicide. There is thus strong evidence that in the U.S., conflicts between students play more of a role, while perpetrators in Germany often seek revenge for a sense of unfairness, holding teachers to blame. Steinhäuser, like others, felt that he had been treated unfairly as a student, as investigations after the fact showed. “The issue here is a subjective perception of unfairness,” Bondü says, “It doesn’t necessarily have to match the reality.”

The specifics of the incidents show where the deficits in Germany lie: in education. This is no wonder, since solid academic findings regarding the risk factors behind shooting rampages have been rare so far, so they have not yet been integrated into the training given to teachers or school psychologists.

In principle, there are no patterns that allow others to make conclusions regarding who will commit these kinds of crimes. That means it is important to monitor students’ individual development closely. The work of the Berlin Leaking Project has contributed to the development of the preventive program “Networks against School Shootings” headed by Professor Herbert Scheithauer at Freie Universität. The incentive aims to help teachers identify suspicious behaviors and changes in students early on and deal appropriately with conflicts.