Open Sesame

In a workshop on Arabic codicology, junior scholars at Freie Universität delve into the treasure hidden between the covers of a book.

Jun 29, 2012

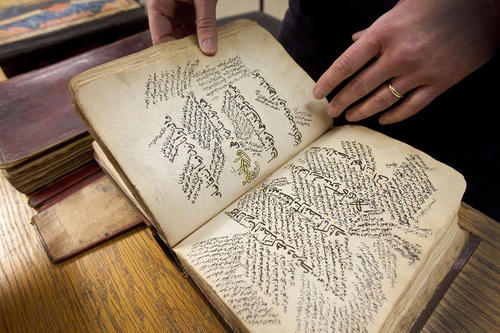

Centuries-old manuscript tradition: The participants of the workshop dealt extensively with the historical sources.

Image Credit: Ernst Fesseler

Anyone who works with historical manuscripts quickly encounters a microcosm of formats, colors, and functions that lend the objects a special degree of veracity and resonance. That is what makes these features so interesting for systematic study by scholars working in the fields of codicology and paleography. These areas are even more important to scholars of the Middle East, where book printing did not become widespread and established until the 19th century. In a workshop entitled “Introduction to Arabic Codicology,” junior scholars and students study the centuries-old traditions of manuscript production in the Arabic-speaking world.

People who open a book or a newspaper today or work with a desktop computer, laptop, or tablet might notice one conspicuous fact above all: just how inconspicuous a largely standardized typeface is. After all, Times New Roman is and remains Times New Roman, no matter which keyboard is used to type it. The printed word – and, perhaps even more so, the digitized word – foster a very specific linear aesthetic. In the age of handwriting, though, things were quite different. Writing by hand, then and now, automatically produces a highly individual script, clearly distinguishable from the writing of others.

That fact alone might lead us to believe that the individual practice of handwriting is unique and incomparable. Academic studies of historical manuscripts soon tell a different story, though. Very little was left to the author’s individual preferences or inclinations. The medium of script was evidently also subject to certain prescriptions and proscriptions – rules that an author had to follow if he wished his works to be read, cited, and received by others. And, in fact, this art was reserved at the time for a small, select group of those learned in the use of script, distinguished by their special knowledge.

Now, that very same special knowledge is what Professor Sabine Schmidtke, the director of the Intellectual History of the Islamicate World research unit at Freie Universität Berlin, and Christoph Rauch, the head of the Middle East Department at the Berlin State Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), aim to unlock for participants in the workshop they organized, “Introduction to Arabic Codicology.”

“Slide your finders across the pages and feel the hairy side of the parchment,” Adam Gacek told his audience at the start of the course. By bringing in Gacek, a celebrated professor of Arabic language and literature and the former head of the Islamic Studies Library at McGill University, in Montreal, organizers were able to include one of the world’s leading specialists in Middle Eastern codicology and paleography as a speaker in the workshop series.

It quickly became clear to the course’s 50 participants that learning to read Arabic manuscripts means, first of all, looking at every aspect of the object – except the actual content of the written text. For one thing, there’s the feel of the manuscripts. Depending on the handling, density, and volume, scholars can draw conclusions about the quality of the paper used, and thus about the age of the manuscript and its geographic origin. The nature and color of the ink, which was used in black, red, green, and blue, can also give present-day researchers clues about the ink itself and those who used it; bright-blue ink made from lapis lazuli, for example, was used exclusively in Persian texts. The script itself also tells a number of things about the manuscript’s author and how the text was created. The more the author inserted, corrected, abbreviated, struck, or noted in the margins, the more likely it is that the manuscript is a draft rather than a final, copied version. A final clean copy is substantially better organized and easier to read. And finally, the individual nature of how pages are arranged is another noteworthy feature, since it also reflects the organization of knowledge in that content is weighted by being arranged from the inside to the outside. The core content is placed at the center of the page, encircled concentrically by the commentary and metacommentary. The fact that there is generally a substantial margin left around that indicates that the writer was thinking ahead to the possibility of further textual notes, either by the author or by others.

The workshop is teaching important skills that are now in greater demand than ever, especially as previously unexplored manuscript collections are becoming available for study, not only by the academic community itself, but increasingly also by Arab nations, conscious of their own cultural history and roots. This development is also marking a change in the direction of research, which is moving back toward fundamental research in Islamic studies and related disciplines.

Like the famous treasure cave opened by Ali Baba in One Thousand and One Nights using the phrase “open sesame,” researchers are opening up a largely unexplored field, filled with the gleaming treasures of the past – treasures that will probably be able to tell us more about our present and future than we can see at first glance. Unlocking that knowledge is the power and drive that lie at the heart of studying historical manuscripts.