Tracing the History of Germany’s Oldest Mosque

Archaeologists from Freie Universität have found remnants of the first Muslim house of prayer

Nov 16, 2015

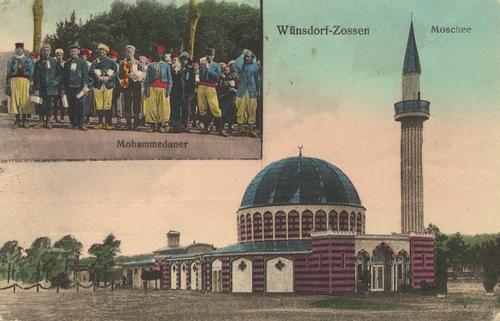

This postcard from 1916 shows the wooden mosque at the “Half-Moon Camp” (Halbmondlager) near Wünsdorf, a prisoner-of-war camp during World War I.

Image Credit: Wilhelm Puder/Wikimedia Commons

Tank parts covered with concrete and a tile from a pit near a military tank repair shop.

Image Credit: Brandenburgisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologisches Landemuseum/Prof. Dr. Susan Pollock

Excavating the area around the mosque. In the foreground is the foundation of a tank hangar from the Nazi era.

Image Credit: Brandenburgisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologisches Landemuseum/Prof. Dr. Susan Pollock

The first mosque in Germany was built a hundred years ago, about 40 kilometers south of Berlin, in the town of Wünsdorf – but the wooden building only stood for fifteen years. In cooperation with the Brandenburg State Office of Historical Preservation, Reinhard Bernbeck, Susan Pollock, and their team from the Institute for Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology spent the last few weeks searching for the remnants of the mosque.

“We had a highly detailed building description of the mosque from 1916, which made our work easier,” says Bernbeck. He and his team spent several weeks working with archaeologists from other institutions, searching for traces of the house of worship in the area in Brandenburg. It was a tough undertaking, especially because the mosque and minaret were built entirely of wood and were demolished more than 80 years ago.

Wires, Bolts, and Shards of Glass from Windows

Still, the archaeologists found what they were looking for, about a meter belong the surface. “The wooden cupolas were braced with iron parts and bolts. We found the bracing wires and bolts during the excavation work,” Bernbeck says. Green and blue glass shards from the mosque’s windows were also unearthed. These finds were located in the areas to the south of the mosque. “You can see from this that the mosque was systematically dismantled,” the archaeologist explains. The wood and iron parts that were still usable were reused elsewhere, as were the “Rathenow bricks” that had been used to line the floor and forecourt of the house of prayer.

At the end of the dig, the team was also able to identify the mosque’s exact location. “Before the dig started, all we could say was that the mosque had stood within a certain radius,” Bernbeck says. The team has now determined that the area that was excavated was the southern front building of the mosque, where the minaret must also have been located. The prayer room itself and the forecourt, which extended past the mosque to the north, are located under the present-day parking lot and will not be affected further by the upcoming construction work.

Still, only scanty remnants now remain of the building, since the area where the mosque was located suffered heavy damage over the decades that followed.

The “Half Moon Camp”: An Attempt to Make Allies Out of Prisoners of War

The exciting history of Germany’s first mosque is well documented. The house of prayer was first built in 1915 as a “gift” from the Kaiser to the Muslims interned at the camp as prisoners during World War I. That was also how the camp came to be called “Half Moon Camp” (Halbmondlager). The construction was based not on religious tolerance, but military and propagandistic calculations: British, French, and Russian prisoners of war of the Muslim faith were supposed to be motivated to fight against their countries of origin at the camp. But very few prisoners ended up defecting to the other side.

At the same time, the prisoners of war were abused in the name of science. Their languages were recorded, and there was interest in their music and culture – but only as an “ethnological circus of our enemies,” as ethnologist Leo Frobenius said at the time.

After the end of World War I, the mosque was used for a few more years before falling into disuse. It was demolished around 1930. During the Nazi era, barracks complexes and hangars for tanks were built on the grounds. The Wehrmacht High Command was located near the former POW camp from 1939 until 1945. Very soon after World War II, in April 1945, the Red Army moved into the area, which is located in the district of Zossen. About 35,000 Soviet troops and their families were stationed in the blocked-off area, which came to be known as “Little Moscow” among the locals.

In the Ground: Everyday Items from the Soviet Occupation Period

As a result, the archaeologists from Freie Universität primarily found traces of the area’s eventful military history during the excavations. Many of them date to the Soviet occupation period. “The grounds were the location of a tank repair shop, so we found a relatively large number of tank parts. We also found everyday items: remains of meals, jam jars, beer bottles, and the like.” Wünsdorf was the headquarters of the High Command of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany until 1994. Meanwhile, a street name and a small metal plaque recall the mosque today. Now there are plans to set up trailers for asylum seekers on the grounds.

Further Information

Prof. Dr. Reinhard Bernbeck, Institute for Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology, Tel.: +49 30 838 57017 or +49 15787295964, Email: rbernbec@zedat.fu-berlin.de