A University of Multilingualism

The Language Center of Freie Universität is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year; it is a centerpiece of living linguistic diversity in Dahlem - a diversity that in research ranges from world languages to the smallest minority languages.

May 24, 2023

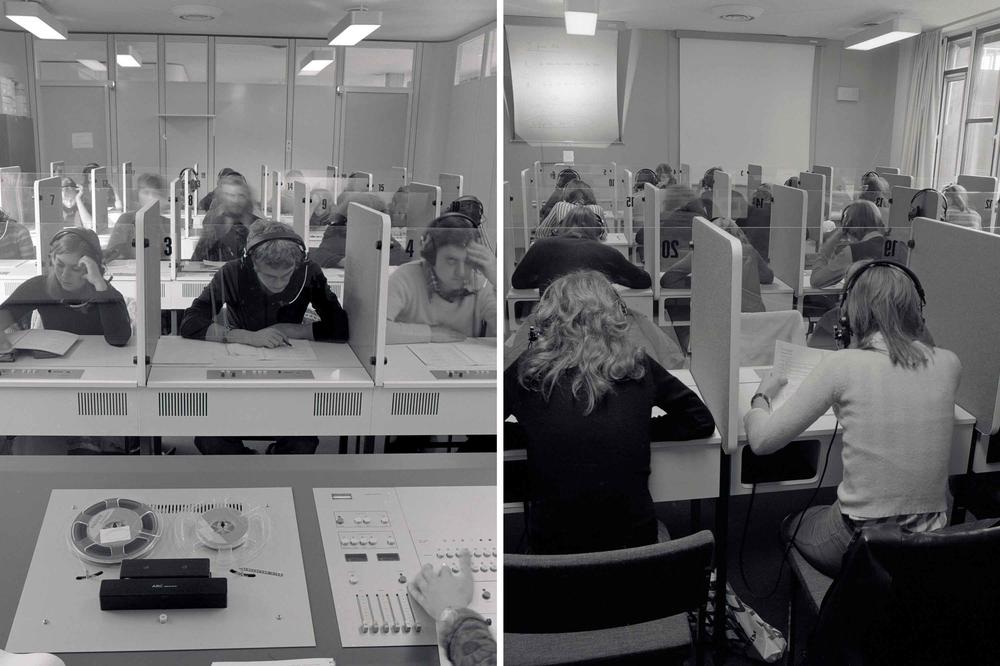

When learning still came from the tape: The Language Center in the 1980s.

Image Credit: Foto: Reinhard Friedrich / Freie Universität, Universitätsarchiv, Foto-S, RF/ 0191-07 (li.) RF / 0191-08

In the late 1950s, Dr. Wolfgang Mackiewicz graduated from high school with an A in English. But when the current honorary professor of English philology met a native speaker for the first time a short time later, he didn't understand a word. "Languages," he recalls about half a century later, "were learned like Latin back then, with lots of translation and grammar exercises, but not as a means of communication." The so-called "communicative turn" did not enter language teaching until the 1970s. Instead of stubborn cramming, the focus was on playful practice and application of the language in various contexts, including everyday life.

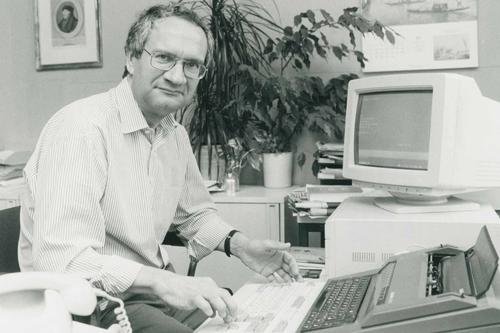

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Mackiewicz, co-founder of the Language Center, initiated several cooperations with European universities.

Image Credit: Inge Kundel-Saro

It was these principles that Mackiewicz and his colleague Harald Preuss took to heart when they founded Freie Universität's Language Center (then called the "Language Laboratory") in 1973 - and built it up over four decades into one of the largest and most important institutions of its kind. "The Language Center anticipated numerous developments in foreign language didactics," emphasizes Dr. Ruth Tobias, language teacher and current director of the Language Center. "From the beginning, the focus was on application and action orientation, a concept that today decisively shapes European standards."

Harald Preuss, together with Wolfgang Mackiewicz, turned the Language Center into one of the largest and most important institutions of its kind.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

This year, the Language Center of Freie Universität celebrates its fiftieth anniversary. Generations of students from Germany and abroad have learned languages from all over the world here, as have numerous international scholars. Today, around 40 permanent teaching staff teach there. In addition, there are twice as many freelancers. Around 1000 semester hours of language teaching per week are thus accumulated, spread over thirteen different languages. "It all started in the winter semester of 1973/74 with English and French," Tobias recounts. "Then Italian, Russian, Spanish and German as a foreign language were quickly added." In the 2000s, Arabic, Japanese, Portuguese, Turkish, Dutch, Persian and Polish were also added to the offerings.

Dr. Ruth Tobias, Director of the Language Center: "We live multilingualism in everyday life, both in terms of our foreign language competence as well as the students' languages of origin and the daily work with the colleges."

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Students of all subjects have the opportunity to take courses in the language of their choice as part of the General Professional Preparation of their bachelor's degree. International students and faculty can attend German courses free of charge. A special feature of Freie Universität's Language Center is also that foreign language training for a number of degree programs in the philologies and cultural studies takes place here. "Prospective Islamic Studies students learn Arabic or Turkish with us, for example," says Tobias. "Future Romance scholars learn Portuguese or Italian."

Cooperation with universities throughout Europe

Freie Universität thus has a proven institution in the form of the Language Center, in which the competencies for foreign language teaching are centrally gathered under one roof. In addition, it stands for international networking. As early as the early 1980s, founder Mackiewicz used his good contacts with the British Council to organize an exchange program with five British universities. When the states of the then European Community decided to introduce the Erasmus exchange program in 1987, it was logically located at the Language Center at the beginning. In the very first year, Mackiewicz initiated cooperation with universities in Padua, Thessaloniki, Amsterdam, Grenoble, Dundee and Paris. Today, the founder of the Language Center is also considered the "midwife" of the Erasmus program at Freie Universität. Since Ruth Tobias took over the management of the center in 2011 from the dual leadership of Wolfgang Mackiewicz and Harald Preuss, she has continued the international strategy. Recently, for example, she established a partner program with the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. "We cooperate with universities throughout Europe, as well as with leading cultural institutions and embassies," Tobias emphasizes. "We see ourselves as a center of European language policy."

One of Tobias' biggest projects to date was a comprehensive mission statement process. For more than a year, staff members came together in various constellations. "The previous mission statement of the Language Center was 20 years old. So we wanted to re-clarify who we are and what we stand for," Tobias says. "And we wanted to frame this as a bottom-up process in which everyone has a voice." The new mission statement appeared just in time for the fiftieth anniversary under the heading "Multilingually Networked Together." There, the institution not only commits to the goal of educating culturally competent, multilingual and cosmopolitan students and promoting student mobility and internationalization, but also clarifies its self-image as a place of social diversity. "We live multilingualism in everyday life," Tobias emphasizes, "both in terms of our foreign language competence and the students' languages of origin, as well as the daily work in the college." Not only has the language center changed over the past 50 years, he says, but so have the students. "Many of them no longer come to us with only one first language. They already innately speak two, maybe even three languages." Such cultural diversity, he said, is a treasure that must be nurtured. "These young people have very different ways of dealing with language," Tobias points out. "The incredible enrichment of multilingualism is something we as a society should appreciate even more."

Germanist Dr. Japhet Johnstone is responsible for the "Central Translation Office" at Freie Universität.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Multilingualism is also promoted at Freie Universität beyond the Language Center. In order to do justice to its international role, almost all documents of the departments and central institutions are now also available in English. Four years ago, the "Central Translation Office" was set up specifically for this purpose, based at the Office of Communications and Marketing. The office was set up by the American German scholar Dr. Japhet Johnstone. "We are strengthening Freie Universität as an international network university," he emphasizes, "and at the same time ensuring greater diversity and openness among students." There are now five employees working in the translation office. They translate Freie Universität publications from German into English. These range from greetings from the president to examination regulations and administrative forms.

One of the most important tasks is also dealing with terminology. How, for example, should one translate "university framework law," "institute council chairman," or "operational integration management"? "The language at German universities and administrations has numerous idiosyncrasies for which there is often no clear English-language equivalent," Johnstone points out. "We clarify such cases and establish uniform solutions in consultation with relevant departments." The Central Translation Office is thus an important internal university language facility. "Translating administrative texts and student examination regulations may not always be fun," says Johnstone. "But we're motivated by the fact that we know: By doing this, we're making it much easier for people from very different backgrounds to access university education."

Sinologist Dr. Andreas Guder has established one of the first degree programs in Germany in which Chinese can be studied for a teaching degree.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Of course, languages also play a central role in research at Freie Universität. In "Rostlaube," "Silberlaube," and "Holzlaube," which are home to the humanities, linguistics, and cultural studies, countless scholars work on languages from all regions of the world. One expert on Chinese is Dr. Andreas Guder. The sinologist has been teaching in the "Holzlaube" since 2019 as a professor of Chinese didactics and Chinese language and literature at the Institute for Chinese Studies. There, he has established one of the first degree programs in Germany in which Chinese can be studied for a teaching degree. "Chinese is a very difficult language for us," he emphasizes. "You have to be prepared to make slower progress than with English or French." Still, he advocates taking on the challenge. Learning a language that is completely different, both in its linguistic characteristics and in its cultural customs and writing system, he says, is learning about the world and about oneself in a whole new way. In a certain way, one experiences the relativity of our European world view.

Chinese for the teaching profession

What makes Chinese so difficult is not the grammar, the sinologist explains. In fact, it is extraordinarily easy compared to the grammar of European languages. But Chinese is a tonal language. "Syllables that are identical in phonetic structure can take on a completely different meaning, depending on the pitch at which they are pronounced," Guder says. "You have to develop an ear for that first." In addition, the writing system is one of the most difficult and complex in the world. Chinese lessons therefore require a particularly intensive form of language acquisition, he says. "You have to apply different standards than with related languages," Guder emphasizes. "We can't assume that students will be able to speak business Chinese to a professional standard after just a few semesters." In the bachelor's program "Chinese Language and Society," students acquire knowledge in cultural, linguistic as well as social science modules and learn Chinese over four semesters with eight to ten hours per week. In the coming winter semester, the first cohort will continue with the "Master of Education" in the teaching degree program in Chinese. Upon graduation, students will qualify to teach Chinese throughout the secondary school system. "In almost every state, Chinese is already a baccalaureate subject," Guder says. "The demand for teachers with Chinese plus a second subject will increasingly increase."

Linguist Prof. Dr. Uli Reich knows a thing or two about little-spoken languages: "There are around 7000 living languages in the world, by far the majority of which are spoken by fewer than ten thousand people."

Image Credit: privat

Measured by the number of about one billion native speakers, Chinese is the most widely spoken language in the world. But at Freie Universität, there are not only experts on this world language. Numerous researchers also work on languages that only a few thousand people (still) speak. One of them is Dr. Uli Reich. "There are around 7,000 living languages in the world," he points out. "Of these, by far the majority are spoken by fewer than ten thousand people." Reich is a professor of Romance linguistics. Originally, the Spanish and Portuguese languages formed his research focus. But for many years he has also been studying the indigenous languages of South America, particularly Nheengatú, a language spoken by only about 7,000 people, most of whom live in the border region of Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela. "About 200 years ago, Nheengatú was still spoken throughout Brazil," Reich says. "But then the prohibition of the language by the Portuguese was enforced everywhere by the formally already independent Brazilian Empire in the 19th century." The paradox: It was the Europeans themselves who once spread the language in Brazil.

Languages mean diversity

"The historical source language of Nheengatú, Tupinambá, was only spoken in the coastal region between São Paulo and Bahia. There, however, the language was learned by European missionaries and spread throughout the country." Today, he said, its prevalence is in sharp decline, like that of many other indigenous languages of Brazil. "Many young people have little interest in maintaining the language," Reich says. "They are totally socialized in the Portuguese language." Some indigenous languages are on the verge of extinction in Brazil. In some cases, they are spoken by only a few hundred people. Under the right-wing nationalist government of Jair Bolsonaro, indigenous minorities have also suffered years of discrimination. "Under the new president, Lula da Silva, the cultural autonomy of the indigenous population is now being strengthened again," Reich says. "There is explicit encouragement to create cultural offerings in minority languages, such as music or series." Cultivating small languages is of great cultural value, Reich emphasizes. "Every language is a special way of perceiving the world," he says. "With every language that dies out, we lose a piece of diversity in the human way of life."

Veronika Solopova is a computational linguist: "The way of learning languages will change a lot, for example through ChatGPT." As part of her PhD, she is working on an app to support young people in teacher training.

Image Credit: privat

Concerns about a loss of linguistic diversity are currently also arising in light of growing advances in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). The publication of the ChatGPT program has triggered a worldwide debate about the status and future of translation and language mediation. Will work in translation agencies soon be done by machines? Will people in the future still laboriously learn Chinese when they can communicate via apps? "The way of learning languages will change a lot, for example through ChatGPT, that's where we will adapt," says Veronika Solopova. The computational linguist is herself active in the AI field. She is a research associate at the "Dahlem Center for Machine Learning and Robotics" at the Institute of Computer Science at Freie Universität. As part of her doctorate, she is working on the development of the "PetraKIP" project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, an app designed to support young people in teacher training. "Some AI developers certainly think in purely mathematical terms," she says. "Content is secondary for them; what matters is the algorithm." But Solopova emphasizes that she is not only a programmer, but also a linguist. She herself speaks seven languages. "In the future, people will probably learn languages less as a means to an end," she says, "but joy and passion for linguistic diversity will always remain."

By Dennis Yücel