Historical Research and Political Contra

75 Years after the End of World War II: Historian Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe does research at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute on whether Polish mayors supported German occupiers in persecuting Jews.

May 23, 2020

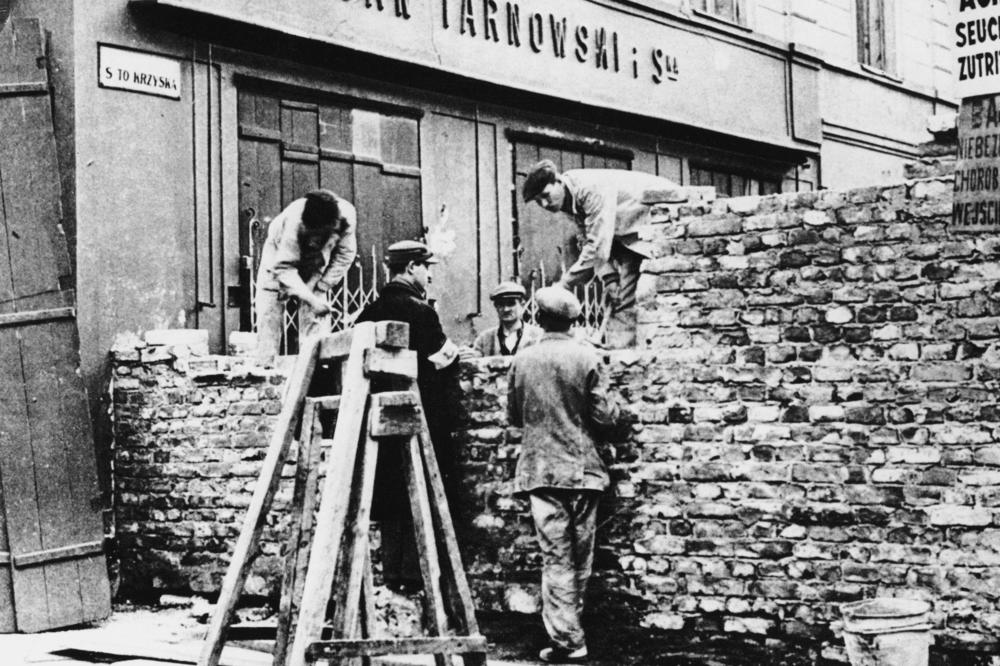

Warsaw 1940: Construction of the Ghetto Wall on Świętokrzyska Street.

Image Credit: picture alliance-AKG Images

For decades there has been disagreement in Poland over the question of whether Polish citizens supported the German occupiers in the persecution of Jews during World War II. Previous studies provide evidence that there was extensive collaboration. But not everyone in Poland wants to acknowledge the findings of historical research. This makes it even more important for historians to do further research on the Holocaust and present their findings.

Historian Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe studied at European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder) and earned a doctorate at Universität Hamburg. He is currently working at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute at Freie Universität Berlin, where he is writing a book on the role of Polish mayors in the General Government during the German occupation in World War II. His work examines the biographies of twelve Polish mayors, using examples to look into the relationship between them and their German superiors.

Rossoliński-Liebe has completed 60 percent of his study and is currently working on the chapter that highlights the involvement of Polish mayors in the Holocaust. He points out that antisemitism was widespread among all classes in Poland before World War II, including local politicians. This antisemitism contributed to the fact that many mayors implemented the antisemitic regulations of the Germans with great accuracy and without contradiction. There were no protests from the city administrations. Rossoliński-Liebe says, “As a rule, the mayors and the municipalities took advantage of the situation of the Jews and enriched themselves at their expense.” Apartments and valuables were confiscated, and Jewish fellow citizens were deported to Treblinka, Bełżec, or Sobibór. According to Rossoliński-Liebe, the respective mayors, bailiffs, and city administrations were involved in all of these actions.

But not only that: Mayors had a say in the size of the ghettos, their location and condition, which districts or streets belonged to the ghettos and which didn't, and who got the vacant apartments afterward. They also made massive use of Jewish forced labor to build new roads in their communities. There were few offers of aid or rescue attempts. Rossoliński-Liebe says, “Sometimes city administrations such as those in Warsaw issued ID cards to Jews or hired them in the local government to protect them from the National Socialists. However, this happened rarely. A few mayors helped their Jewish fellow citizens privately with their families, but that was the exception and certainly not a mass phenomenon.”

Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe expects to complete his study next year. He is aware that the publication will not please everyone in Poland, and he also expects dissenting voices in Germany. He is already being attacked by historians close to the government in Poland. His colleagues at the Polish Center for Holocaust Research in Warsaw with whom he collaborates also have to live with harassment and without financial support from the government. “In the long term, that doesn't change much,” he says. “Holocaust research is networked worldwide and won't be prevented. Despite the political headwind, the murder of Jews in Poland, like in many other countries, will continue to be further investigated.”

The original German version of this article was published on May 15, 2020, in campus.leben, the online magazine of Freie Universität Berlin.