Momentous Discovery in Dahlem

In 1938 chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann observed nuclear fission – Physicist Lise Meitner provided the explanation, and Otto Hahn won a Nobel Prize.

Dec 22, 2021

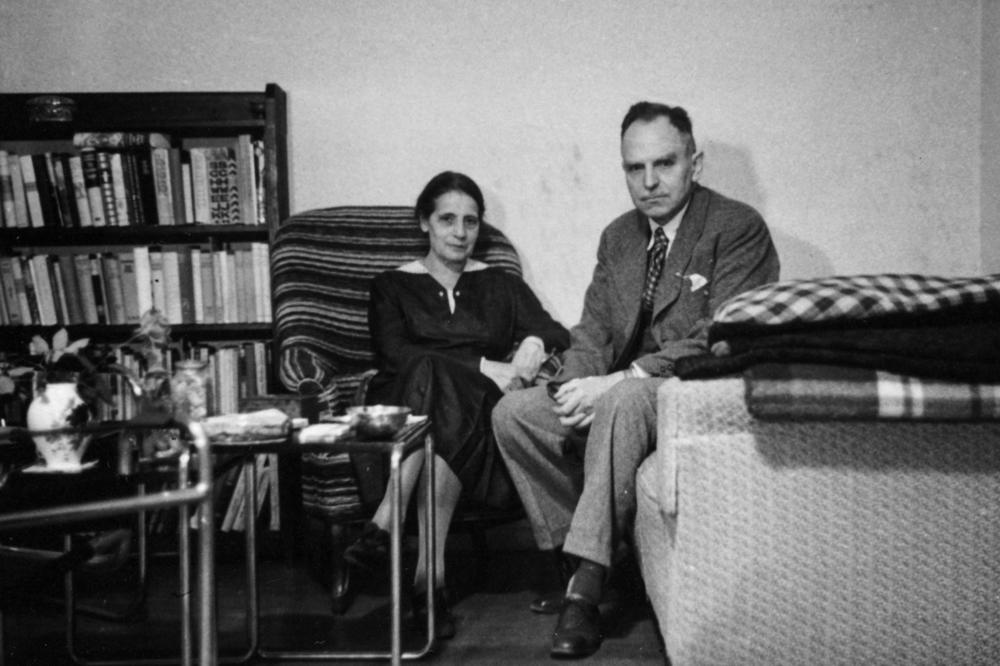

Physicist Lise Meitner, on the evening before she fled into exile in July 1938, seated next to her colleague Otto Hahn. December 10, 2021, is the 75th anniversary of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Otto Hahn.

Image Credit: Archive of the Max Planck Society, Berlin-Dahlem

With its column-framed portal and fortress-like tower, the Hahn-Meitner Building stands out among the numerous impressive Wilhelminian-style buildings in Dahlem’s science district. The building has been used by the Institute of Biochemistry at Freie Universität Berlin since 1980. On December 17, 1938, it was the scene of a great moment in science: Here chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann discovered nuclear fission, the basis for the peaceful use of nuclear energy, but also the atomic bomb.

Jens Peter Fürste, who holds a doctorate in biochemistry, is something like a living memory of the building. After studying biochemistry at Freie Universität and doing research at the University of Colorado, Fürste returned to Berlin as a research assistant and began to be interested in the history of the Dahlem science district. If you hear him talk about the discovery of nuclear fission, it sounds as if Fürste had been there back then.

Fission of the Uranium Atom

“On Friday, December 16, 1938, Fritz Straßmann went into the irradiation room to bombard uranium atoms with slow neutrons,” Fürste begins.

It was an experiment similar to those being done by other scientists around the world at the time. Their hope: the neutrons would be absorbed by the uranium and form a transuranium, an atom even heavier than uranium, the heaviest atom known at the time. “When he came back on Saturday morning – back then you still worked on Saturdays, and Straßmann liked to start early – he got the sample and separated the elements,” Fürste says. He points to a three-dimensional reconstruction of the experimental rooms on the computer monitor in his office. The original no longer exists.

“At noon, Straßmann’s colleague, the well-known chemist Otto Hahn, returned from the tax office,” says Fürste with a smile. “Apparently something on his tax return needed clarification.” Hahn then carried out the radioactive measurements on the separated elements. The results were surprising, and the two researchers both reached the same conclusion: the uranium atom had been split. But how did it come about?

Lise Meitner Also Deserved the Nobel Prize

Otto Hahn wrote to his long-time colleague Lise Meitner and informed her about his discovery. Fürste points out, “That was a considerable risk for Hahn because Lise Meitner was of Jewish descent and had fled Germany.” But Hahn had more than thirty years of trusting scientific collaboration with Meitner. “Together they were an absolute power package,” says Fürste.

Chemist Hahn needed the expertise of the brilliant physicist Meitner. And Lise Meitner delivered: Together with her nephew Otto Frisch, a physicist at the University of Copenhagen, she published an explanation of nuclear fission. It was advantageous that she had designed the experiment that Hahn and Straßmann had then carried out.

Jens Peter Fürste is convinced that “if she had been able to continue working in Berlin, she would have become a co-author of the the publication and would have received the Nobel Prize along with Otto Hahn.”

Together with colleagues from Freie Universität Berlin, he therefore campaigned for the building that used to be named after Otto Hahn to be renamed Hahn-Meitner-Bau (Hahn-Meitner Building). In 2010 Freie Universität had a plaque of honor for Lise Meitner put up on the front of the building. In an academic ceremony in 1956, Meitner had already received an honorary doctorate from Freie Universität. She died in England in 1968.

A great moment in science, full of ambivalence: Today the Hahn-Meitner Building, where nuclear fission was discovered, houses the Institute of Biochemistry at Freie Universität Berlin.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Jens Peter Fürste has a photo of Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn. The two are sitting close together, an expression of decades of collegial friendship, but also a painful farewell. It is their last meeting before Meitner fled from Germany on July 17, 1938.

Hahn and Peter Debye, who was a Dutch national and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, helped Meitner escape. “After her Austrian homeland was annexed to the German Reich, Lise Meitner would have been outlawed because of her Jewish origins. She would have been deported sooner or later,” explains Fürste.

The Hitler regime recognized the potential of nuclear fission to build an atomic bomb, as did the Allies. The Allies bombed the building of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (today’s Hahn-Meitner Building) in 1944. “The Allies feared that an atomic bomb would be developed here in Dahlem,” explains Fürste. The building was partially destroyed in the process. Otto Hahn’s office and all of his correspondence were burned.

Otto Hahn Never Considered Himself the Father of the Atomic Bomb

World War II was over before Otto Hahn, who was in British captivity, learned that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944 for his discovery of nuclear fission. He never saw himself as the father of the atomic bomb. Nor did Lise Meitner, who suffered from being called the mother of the bomb.

Fürste can understand this. “It was not possible to foresee the atomic bomb from the experiment of December 1938. None of those involved knew that further neutrons would be released during nuclear fission, leading to a nuclear explosion.” As Fürste points out, “You can peel an apple with a knife, but you can also kill someone with it.” Today experts refer to this issue as dual use.

For Jens Peter Fürste, the Hahn-Meitner Building is not only his place of work as a biochemist and the seat of his institute, but also a place of remembrance. He now gives guided tours through the Dahlem Science Quarter to pass on his findings to conference participants from all over the world and to students at Freie Universität.

This text originally appeared in German on December 4, 2021, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.