Remembering the Wall

Work began on the Berlin Wall sixty years ago, cementing the division of Germany for the next forty years. How should this period be commemorated? Researchers and students at Freie Universität Berlin shine a light on this era of German history.

Jul 28, 2021

Cold War relic: This reproduction of the Checkpoint Charlie guardhouse can be found where it once stood. The original, dismantled during a ceremony attended by foreign ministers in June 1990, is now at the Allied Museum in Dahlem.

Image Credit: Hanno Hochmuth

If you’re looking for a prime example of the debates that have plagued commemorations of the peaceful revolution and German reunification in recent years, then look no further than the proposed “Monument to Freedom and Unity” (or the “Unity Seesaw,” as it has been dubbed). The installation, which visitors would have been able to walk onto and set in motion – hence “the seesaw” – has been shelved for the last 13 years due to controversies surrounding its cost, location, and design.

“There has been no cross-societal consensus on how we should evaluate the history of the GDR,” says Hanno Hochmuth. The historian, who teaches in the master’s degree program “Public History” at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute at Freie Universität Berlin, also works at the Leibniz Center for Contemporary History Potsdam (ZZF). “We tend to oscillate between focusing on the horrors of the dictatorship to easing into an insidious kind of nostalgia,” he explains.

The sixtieth anniversary of the construction of the Berlin Wall on August 13 has inspired a wide array of research and publication projects at Freie Universität Berlin, especially since the history of the university (founded in December 1948) is closely interwoven with the post-war period and the division of Germany. “A great number of students were involved in helping East Germans escape in the years following the construction of the Berlin Wall,” says Dr. Jochen Staadt. The German literary scholar and political scientist is a member of the Forschungsverbund SED-Staat (“Research Association on the SED State”) founded at Freie Universität Berlin in 1992, which concentrates on the history of divided Germany and the ripple effects of the SED dictatorship since reunification.

Students Helped East Germans Cross the Border

Students from southwest Berlin hid their peers by the driver’s feet in their cars or in the trunk to transport them from East to West Berlin. They dug tunnels and loaned out their passports so that the photos could be swapped out. By January 1962, students from Freie Universität Berlin had helped over 800 people escape. However, when caught, those attempting to escape and those who assisted them could be dealt hefty prison sentences, and some even paid the ultimate price. According to findings provided by the ZZF and the Berlin Wall Memorial, 140 people were killed or died at the Wall between 1961 and 1989.

The “Iron Curtain” consortium funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research is made up of scholars from Freie Universität Berlin, the University of Greifswald, and the University of Potsdam, who are each focusing on different aspects of the GDR’s legacy. The team of researchers from Freie Universität Berlin are currently undertaking a subproject to investigate the deaths of Germans on the borders of Eastern Bloc states, since, as Staadt says, in contrast to the victims of the Berlin Wall, hardly any research has been carried out on the deaths of these people.

Attempts to escape via the Baltic Sea are not well-known, but researchers at the University of Greifswald are working to unveil this history. Meanwhile, the University of Potsdam is leading another subproject to research the GDR’s Ministry of Justice, as well as the obstructions of justice it committed against those who wanted to leave and escapees who were caught. In total, about 40,000 people managed to flee the GDR after 1961 in spite of the treacherous Berlin Wall and booby-trapped inner German border.

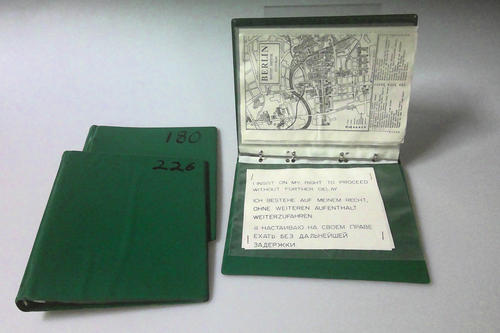

Instruction manual for East Berlin: This folder with a city map and tips on how to behave in the East (left) was issued to help US soldiers in an emergency.

Image Credit: Jennifer Gaschler

How Is History Presented and Commemorated?

Students in the “Public History” master’s degree program, most of whom were born after German reunification, have also been asking important questions about divided Germany. The joint degree program between Freie Universität Berlin and the ZZF not only prepares students for work at commemorative sites, institutions for political education, and museums, but also addresses how we should create new formats for conveying history to the public and what shape our commemorative culture should take.

These students are engaging in discussions on the history of the post-war period that go far beyond the debates that were taking place just twenty years ago, claims Hanno Hochmuth. Until recently, the Cold War has been primarily told from a highly Eurocentric perspective with stereotypes of the East versus the West, the Soviets against the Americans. “Yet the global conflict almost escalated into full-out war several times in Cuba, and reached bloody conclusions in Vietnam, Korea, and in parts of Africa,” says Hochmut.

The historian is planning a virtual exhibition with his students to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the confrontation between US and Soviet tanks at Checkpoint Charlie on October 27, 1961. The everyday history of divided Berlin and its perception across the world form the focus of the exhibition. The history it conveys is told through objects.

A Unique Travel Guide

US soldiers who drove into the Soviet sector via Checkpoint Charlie were always given a special kind of travel guide featuring an information folder with a map of East Berlin, a code of conduct, and Russian translations of phrases like “I insist on my right to proceed without further delay” that could be shown in emergency situations like if their vehicle broke down.

The goal of the exhibition is to depict the most well-known border crossings in the city from a fresh perspective, far from the heavily circulated, imposing images of tanks and heavily armed soldiers we are all familiar with. This digital exhibition will be shown on the “Chronicle of the Berlin War” website, a joint project between the ZZF, the Federal Agency for Civic Education, Deutschlandradio, and the Berlin Wall Foundation. It will be presented at the annual conference of the International Federation for Public History, which will take place at Freie Universität Berlin in August 2022.

Public history student Thomas Köhler is specializing in the GDR’s history as told through material culture. Here he can be seen in a reconstruction of a grocery store at the GDR Documentation Center in Perleberg.

Image Credit: Thomas Köhler

The GDR Documentation Center in Perleberg

Sophie Lutz, together with three of her classmates and a student film team from Ostwestfalen-Lippe University of Applied Sciences and Arts (in Lower Saxony), has organized a public history project in Perleberg in northwest Brandenburg. The married couple Gisela and Hans-Peter Freimark, who live in Perleberg and are both pastors, began to collect objects in the 1980s to document the political system, everyday life in the GDR, and the couple’s opposition to the regime by means of their own family history.

“We thought about how a very personal, anecdotal museum tour could itself be preserved in the long run,” says Thomas Köhler, a student in the “Public History” program. “In every room we decided to exhibit an evocative object with information on its background,” Gisela says, showing off a dress that her mother made her for her school graduation ball.

“It is essential that we understand how the structures in which we exist today came into being,” says Josephine Eckert, who was encouraged to participate in the film project by her lecturer Irmgard Zündorf from the ZZF. Because the everyday history of the GDR is not very visible or well-known in the federal states that were once West Germany, the private collection is designed to give students a tangible insight into the past.

Eckert notes that many terms used in the everyday language of the GDR – a country notorious for its abbreviations – would have been out of use by the time they were born, including “LPG” (Agricultural Production Cooperative), “KB” (Cultural Association), or “making it over” (slang for “escaping from East to West Germany”). In order to contextualize these terms, they designed a website that features video interviews with the Freimarks, which can also be accessed during a tablet tour of the Documentation Center in Perleberg.

Shifting Historical Perspectives

Whose history is being told in museums on the GDR and from whose perspective is the subject of Lotte Thaa’s research. The historian completed her doctorate as part of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research’s joint research program “The Legacy of the GDR in Media: Actors, Appropriation, and Handing Down History” within the History Education division of the Friedrich Meinecke Institute at Freie Universität Berlin. This joint research association involves Freie Universität Berlin, the ZZF, and Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

When it comes to the educational function of museums, they have tended to emphasize a “shortage narrative” from a West German perspective. This black and white comparison with the Federal Republic of Germany foregrounds what commercial goods weren’t available in the GDR and the infamous shortages of everyday products. Thaa says that the underrepresentation of foreign contract workers from countries such as Vietnam, Angola, and Cuba in permanent exhibitions on the GDR, many of whom faced deportation after 1990, is an example of the one-sidedness of this narrative. In her analysis of the history of collections and exhibition practices at museums on divided Germany, the historian found only isolated queer perspectives. That’s why she wants to increase the visibility of these stories with her exhibition “Rosarot in Ost-Berlin: Hard-Won Spaces in Changing Times” at the Schwules Museum, a museum devoted to gay art, history, and culture in Berlin’s Schöneberg neighborhood.

“Exhibitions that center on everyday life in the GDR are often accused of downplaying and even trivializing the East German dictatorship,” says Julian Genten. “The commemorative landscape of the Nazi period is much more homogeneous and negative in nature.” Genten is conducting doctoral research on how visitors to GDR museums today interact with history on the basis of their different social and biographical backgrounds. A clear trend has emerged in the course of the interviews he conducts at the end of these visits: “My questions tend to focus specifically on the exhibition – the answers, on the other hand, rarely do.” How the visitors interpret what they have seen strongly depends on their own experiences and expectations. The visit often serves as a prompt for them to tell personal anecdotes or outline their own political perceptions.

Germans who were born after 1989 in particular seem to be interested in questioning their own identity and exploring their family history when they visit commemorative sites and museums on the history of the GDR. This bodes well for researchers and experts in this field, who are sure to find a receptive audience for their work in the future.

This text originally appeared in German on July 3, 2021, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.

Further Information

The Construction of the Berlin Wall and Checkpoint Charlie

On the morning of August 13, 1961, the East German police force, Combat Groups of the Working Class, and the National People’s Army began to erect a border between East and West Berlin on the orders of the East German government. This was intended to stop emigration from East to West Berlin through the border that had been open up to that point.

Just a few weeks later on October 27, the situation escalated at the crossing point Checkpoint Charlie with a sixteen-hour standoff between US and Soviet tanks on either side. One of the most dangerous crises of the Cold War was provoked when a GDR border guard stopped a US officer crossing into East Berlin and asked for his identification papers, violating an agreement between the Allies. The heads of state of the US and the Soviet Union, John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev, resolved the conflict by agreeing to withdraw their tanks.