Theater Buildings as a Mirror of Society

A research team made up of members from Berlin’s colleges – including theater scholars from Freie Universität Berlin – are exploring Technische Universität Berlin’s collection of material on theater buildings

Jun 24, 2021

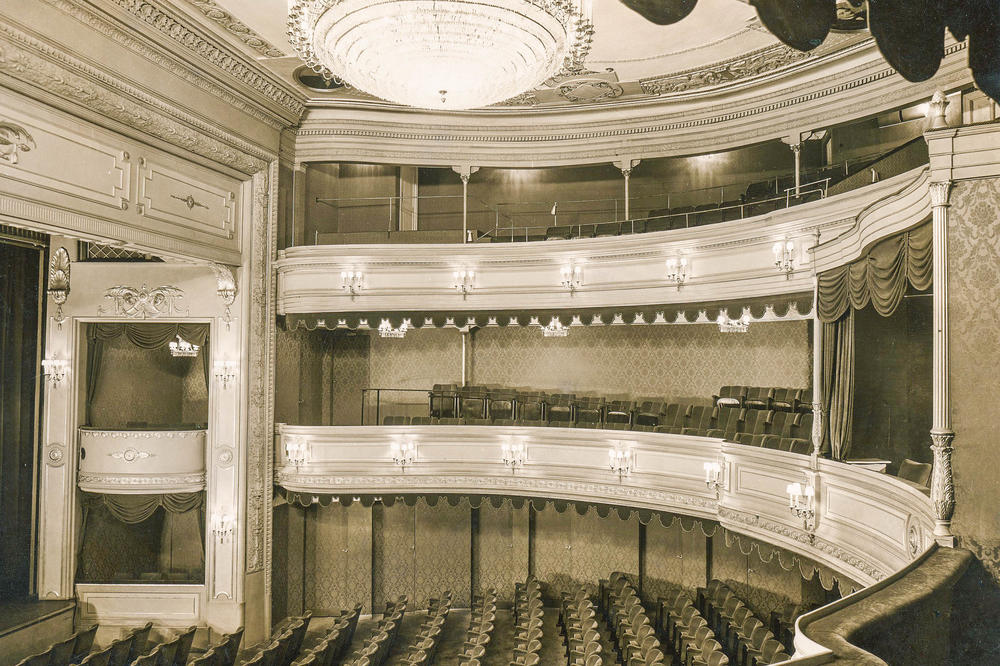

The realities of everyday life and political circumstances are often immortalized in architecture – a prime example being the classical Deutsches Theater in Berlin, designed by the architect Eduard Titz in the mid-nineteenth century.

Image Credit: Theaterbausammlung (theater buildings archive) at Technische Universität Berlin

“Theater buildings reflect the societal conditions of their time,” says Jan Lazardzig, a professor of theater studies at Freie Universität Berlin, “but just like churches, they also bring together totally disparate eras and traditions.” The scholar researches architecture, technology, and the history of knowledge as they pertain to theater. Luckily, he has access to a particularly useful source for his work right here in Berlin at Technische Universität’s Architecture Museum, home to the Theaterbausammlung (theater buildings archive), one of the largest collections focusing on the history of German theater.

600 Photographic Plates of 300 Theater Buildings

The archive consists of about 5000 sources, among them folders with construction plans depicting over 300 theater buildings in great detail, roughly 600 glass plate negatives of theater buildings, an extensive array of teaching materials from the postwar period, and many historical illustrations of stage designs.

Between 2016 and 2018 the collection was made accessible and digitized so that researchers in disciplines as diverse as art, theater, and technology can now enjoy them. Researchers from Technische Universität Berlin, Beuth University of Applied Sciences, and Freie Universität Berlin are currently participating in the research project “Theater Buildings – Epistemic Continuities and Disruptions as Mirrored in the Theater Buildings Archive of Technische Universität Berlin.”

The project, which is to be funded for three years by the German Research Foundation, is divided into three subprojects. The first relates to a plan set in motion by Albert Speer, General Building Inspector for Berlin during the Nazi era, who lay the foundations for the archive. In 1939 he commissioned the publication of a reference guide called “Das Deutsche Theater,” which comprehensively documented all theater buildings in the “Greater German Reich.” Although the project was shelved in 1943 due to the war, it managed to record 319 theaters throughout central Europe, including 32 in Berlin. Kerstin Wittmann-Englert, a professor of the history of architecture at Technische Universität, and doctoral student Franziska Ritter are now analyzing the archive’s documents within the theater buildings project, focusing on the Nazi publication’s architectural photography.

Trade Secrets Were Passed Down from Generation to Generation

The stage hand and professor Friedrich Kranich bequeathed a great deal of the material that now forms part of the archive. Professor Bri Newesely and doctoral candidate Halvard Schommartz are responsible for this subproject at Beuth University of Applied Sciences. This is the only institution of education in Germany with a degree program in theater and event technology – another incredible facet of Kranich’s legacy.

Lazardzig explains that the knowledge of how stage technology worked was considered a trade secret at the beginning of the twentieth century and was only passed down from generation to generation within families. This would have included insider information on how fly systems, special effects, and electrical lighting worked. Kranich was the first person to bring stage technology to the university back in the 1960s, on the basis of the theater buildings archive to which he would later leave his written works. His reference guide Bühnentechnik der Gegenwart (“Contemporary Stage Technology”) and other unpublished manuscripts are now being used to research the standardization of knowledge on stage technology at Beuth.

The third subsection of the project refers to the period at the end of the 1960s when the theater buildings archive became part of the Institute for Theater Buildings’ inventory at Technische Universität. It has since been expanded with items left to the archive by Gerhard Graubner, for example. The professor of design and building theory at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Hannover was not only one of the first proponents of theater construction and stage technology as an academic field in West Germany – he was also highly influential on the theater scene as an architect in the 1950s and 1960s.

Theaters as Reflections of the Historical Era and Zeitgeist

The Institute of Theater Studies at Freie Universität Berlin’s contribution to the research project will be to use the archive to explore how theater construction studies developed as an aspect of postwar modernism. Lazardzig hopes to address questions such as how theater construction was institutionalized, and the role this pooling of knowledge played in the (re)construction of theaters. He is looking forward to answering these questions with Marie-Charlott Schube, a doctoral candidate.

“Theaters are architectural manifestations of the historical era and zeitgeist in which they were constructed,” the researcher says. He explains how the theater was considered an expression of the Völkisch movement and cult of personality surrounding Hitler in Nazi Germany. Many of the cultural buildings that Speer had documented featured special balcony boxes for the elite upper classes, also known as loges. A loge designed for Hitler was incorporated into theater buildings as an architectural reference to this monarchist tradition.

There were different approaches to handling this politically fraught heritage in the postwar period, the results of which can still be seen today. The Deutsches Theater Berlin decided to retain the structure that had been the “Führer’s loge” because it was consistent with its courtly baroque theater style, and therefore would not be negatively perceived as a hangover from the Nazi era. Originally conceived of as a closed-off courtyard theater, a plaza of sorts was created in front of the Deutsches Theater after it was bombed during the war. It was decided that this area would be left open and undeveloped, as German city and state theaters traditionally define their surroundings with their stately buildings.

Max Reinhardt’s Großes Schauspielhaus

While the history of theater construction can be understood through the theater buildings archive, it also helps us to understand how certain cultural venues were reconstructed after the war, such as the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin.

This quintessential example of the turbulent history of theater buildings was initially used as a venue for circus acts, before it was snapped up by Deutsches National-Theater AG and later rebuilt by the architect Hans Poelzig as a theater for the avant-garde director Max Reinhardt. Having been dubbed the Theater des Volkes when it was seized by the Nazis, it was renamed the historic-sounding Friedrichstadt-Palast, expropriated, and run by the socialist state in 1947. In the mid-eighties, the East German government decided to tear down the dilapidated building, and constructed its final incarnation as an imposing revue theater nearby, with seats designed in the traditional Greek amphitheater style and the largest theater stage in the world.

“We see time and time again the attempt to develop new buildings and theater traditions for a new society after major political upheavals. Yet existing knowledge always serves as the foundation for these developments,” says Lazardzig. The theater buildings archive itself testifies to the emergence of vastly different political systems throughout the last century. It is precisely these “epistemic continuities and disruptions” that have caught the interest of the experts participating in the project. Each discipline has a different perspective on this area of research, as Lazardzig confirms: “We start off by discussing our own ideas on theater buildings – from our perspectives on the history of architecture, technology, hands-on experiences, and theater studies – and go through room designs and aesthetic concepts.”

How Should We Think about the Public Sphere?

The project doesn’t just provide us with insights into the past, but also provokes discussion on highly relevant questions regarding the preservation and maintenance of German theater buildings. The theater in Frankfurt am Main is a typical example of how theater construction can become a political issue. Partially destroyed in the war, the building in the city center was rebuilt and expanded in a contemporary style. It is now due a renovation, but there is an ongoing debate on whether a new building should be constructed in the city center or further out.

“The key question here is whether we still have the same conception of the public sphere as these theaters gave rise to.” The theater buildings archive provides us with information on how the architecture of postwar theater was intended to bolster the formation of a democratic society. These massive constructions in the city center were intended to represent a uniform urban community. Instead of loges for the aristocracy, their auditoriums take inspiration from ancient Greece, so that the audience enjoys an unimpeded view of the stage from all angles and audience participation is facilitated.

“Our understanding of historical buildings and the ideas behind their design allow us to rethink theater today,” says Lazardzig. He concludes: “I think that this is also indispensable in terms of how we think about hybrid, separate public spheres, the decline in the importance of the inner city, and the digital developments that have become essential during the coronavirus pandemic.”

This text originally appeared in German on April 24, 2021, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.

Further Information

Prof. Dr. Jan Lazardzig, Freie Universität Berlin, Institute of Theater Studies, Email: jan.lazardzig@fu-berlin.de