What Will Ukraine Need after the War Is Over?

Jessica Gienow-Hecht and Alexander Libman from Freie Universität Berlin evaluate calls for a new version of the Marshall Plan for rebuilding Ukraine

Jul 19, 2022

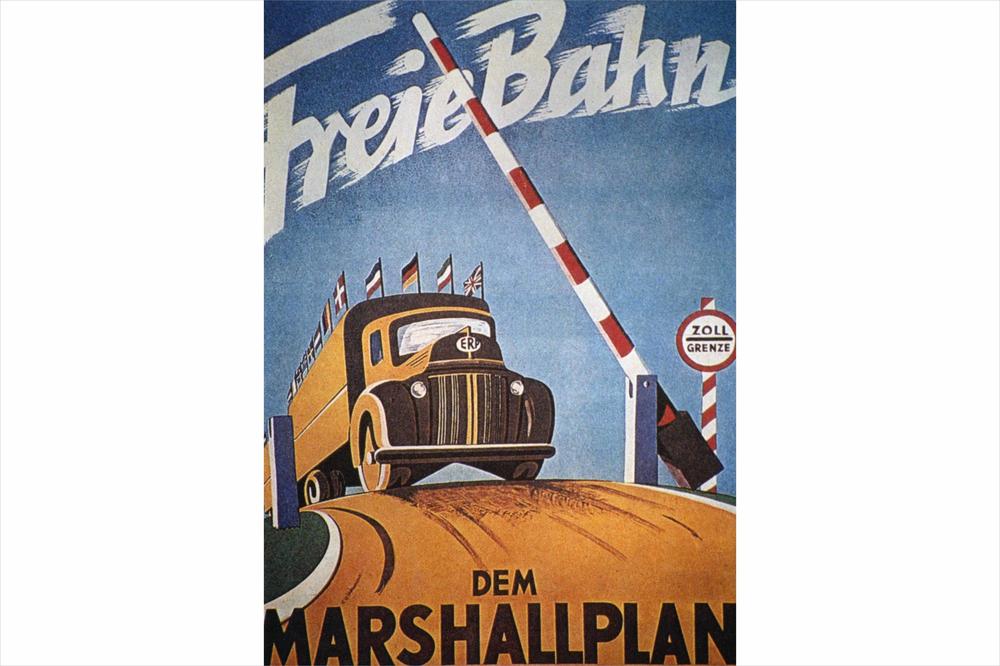

The public relations campaign in the European Recovery Program, popularly known as the Marshall Plan, was part of the US aid program to help rebuild Europe after World War II.

Image Credit: picture alliance-ASSOCIATED PRESS-Ludovic Marin

Images of the siege were on view around the world for weeks. Hundreds of Ukrainian fighters persevered and continued their resistance in the huge steel works of Mariupol while the Russian Army closed in on the steel plant next to the Sea of Azov and continued to bombard it.

This was not the first time that the Azov Steel Metallurgical Combine was affected by war. Built under Stalin in the 1930s and destroyed by Hitler’s troops in World War II, the Azov Steelworks was rebuilt by the Soviets after the war. Now Russian troops attacked and damaged the steel works. In the face of this devastation caused by the Russian war, its owner, Rinat Akhmetov, called for a “new Marshall plan” for the reconstruction of the steel mill and Ukraine as a whole.

Does a Marshall Plan Make Sense for Ukraine?

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, the United States Ambassador to Germany, Amy Gutmann, and the German Finance Minister Christian Lindner have also endorsed the suggestion that Ukraine would benefit from a new version of the Marshall Plan.

How useful would this type of program be? And what does it have to do with the historic program that was presented to the public seventy-five years ago, on June 5, 1947, by the United States Secretary of State George C. Marshall?

Jessica Gienow-Hecht, a professor of history at the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at Freie Universität Berlin, in an interview with Der Tagesspiegel, calls the Marshall Plan the “most significant political project in transatlantic history.”

Announced in 1947 and implemented from 1948 to 1952, the European Recovery Plan, which in Europe was referred to as the Marshall Plan after the person who came up with the idea, supported a total of sixteen countries in recovering from the destruction of World War II and the economic misery of the immediate postwar years. In addition, the plan had the intended effect of dampening sympathies with communist parties, and thereby the influence of the Soviet Union, by raising living standards.

In his speech on June 5, 1947, at Harvard University, George C. Marshall himself put it this way: Europe could not get back on its feet without help from the United States, but it was also in the interests of the United States to provide assistance in Europe’s economic recovery. With regard to the policy, he said, “Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.”

While the Marshall Plan seems to maintain a positive connotation in the collective German memory – as laying the foundation for the economic miracle of the postwar period, boosting the economy of the West, and democratizing the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany – this image is incorrect in several respects..

The United States Wanted a Strong Economy in Europe – and Political Influence

Historian Jessica Gienow-Hecht points out that the scope of the Marshall Plan was probably not large enough to create the impact it is given credit for. It totaled 13 billion dollars, which would be the equivalent of around 115 billion dollars today.

That is less than it might seem, spread over four years and more than a dozen countries. A quarter of the funds went to the UK, a fifth to France, and Germany received around a tenth of the payments. The Soviet Union, which had also been offered help, as had the Central and Eastern European states, soon withdrew from the negotiations and banned the European states under its influence from participating in the program.

In addition, according to Gienow-Hecht, the success of the Marshall Plan was based on more than the distribution of aid funds. It also included a large-scale public relations operation, a “clever mass education program with posters, radio programs, lectures, and more than 280 films viewed by more than 50 million Europeans.”

The main content of the public relations program described the way in which the economy should be rebuilt. The idea was that Europe should emulate the model of the United States economy, that of a capitalist market economy that allows rapidly rising standards of living to grow from mass production, efficiency, and increased productivity.

Gienow-Hecht says, “The consequences of the Marshall Plan went far beyond what both George C. Marshall and the American Congress originally expected.” Indeed, Marshall wanted to create prosperity and ensure that there was peace in Europe.

However, she continues, “He could not have foreseen how incredibly visionary this plan would become, what an inspiration it would be for Europeans, and how long-lasting its impact in Europe and the world would be. For the past seventy-five years we have often been talking about a Marshall Plan: one for Africa, one for the Global South, one for the climate, and now a Marshall Plan for Ukraine.”

French President Emmanuel Macron (right), Romania’s President Klaus Johannis (left), Italy’s Prime Minister Mario Draghi (middle), German Chancellor Olaf Scholz (2nd from right) with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on June 16, 2022, in Kyiv.

Image Credit: picture alliance-ASSOCIATED PRESS-Ludovic Marin

Ukraine and the West

What is the current situation? Would a new Marshall Plan only cover humanitarian aid after Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine? Or would it be more about strengthening Ukraine’s ties to the West and thereby reducing Russia’s influence?

For Alexander Libman there is no doubt that the West would not only be pursuing aid payments with the idea of a Marshall Plan for Ukraine, but also the goal of linking Ukraine more firmly to the West. Libman is a professor of political science at the Institute for East European Studies at Freie Universität Berlin. He says that it goes without saying that these programs have a “soft power” component.

Libman finds it remarkable that politicians in Western Europe in particular are talking about a new Marshall Plan. He says that evoking a collectively remembered success story on which the prosperity of these very countries is based also serves the purpose of addressing taxpayers, who would have to pay for it in the end. Referring to the historical model serves a communication strategy that is geared more toward the donor countries than toward Ukraine.

Rampant Corruption

Both Libman and Gienow-Hecht think that too much hope is being placed in the idea that such a plan could quickly and fundamentally transform Ukraine’s economy. In particular, rampant corruption and the weakness of Ukraine’s institutions will be much more difficult to eradicate than the ruins of war.

Gienow-Hecht points out a specific feature of the historic Marshall Plan that is often forgotten. In order to monitor the distribution of funds and the fulfillment of goals in the European states, there was “a series of measures to accompany the flow of money, such as intensive on-site inspections and the establishment of an independent supervisory authority.”

Would Ukraine agree to such oversight? The Azov steelworks provides an indication of the potential challenges involved in such a plan. Its owner, Rinat Akhmetov, is said to be the richest man in Ukraine. He is an oligarch who owns an extensive network of companies and has also been politically active in the past. As late as November 2021, President Zelensky accused Akhmetov of planning a coup against him, Zelensky.

After the Russian attack, the two put an end to their conflict, and Akhmetov clearly sided with the Ukrainian government. Some observers explain this by saying that he has high hopes for Ukraine’s economic orientation toward Europe and even the European Union.

Libman warns that if Western aid funds do not bring the desired results for Ukraine – due to institutional deficits or a lack of control – or even seep away into corrupt channels, it could lead the population to turn away from the West in disappointment.

All in all, anyone calling for aid for Ukraine under the label of a Marshall Plan would do well to study the historical model closely to see whether and how the country is suitable for a new version of the program.

This article originally appeared in German on July 2, 2022, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.

Further Information

- Professor Jessica Gienow-Hecht, Freie Universität Berlin, John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Department of History, Email: j.gienow@fu-berlin.de

- Professor Alexander Libman, Freie Universität Berlin, Institute for East European Studies, Politics, Email: alexander.libman@fu-berlin.de