Insight into Ultra-tiny Dimensions

Researcher Stephan Sigrist Investigates the Architecture of Synapses

Jan 14, 2015

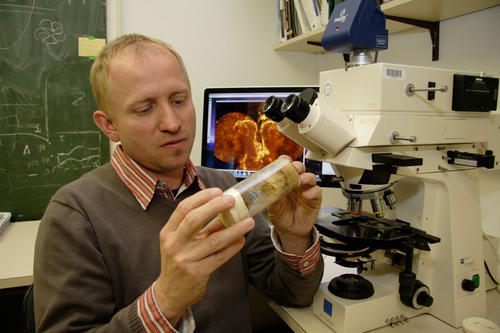

Professor Stephan Sigrist investigates, among other things, the architecture of synapses.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

What controls the structures and functions of the human brain? And how can such knowledge be used for the study and treatment of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, autism, or Parkinson’s disease? These kinds of questions have fascinated biochemist Stephan Sigrist (47) for many years now. “This is my life’s work, and it will probably always keep me busy, since we are constantly discovering new pieces of the puzzle,” he says.

Sigrist, a professor of molecular developmental genetics of animals at Freie Universität, has been doing research within the “NeuroCure – New Perspectives in Treatment of Neurological Diseases” cluster of excellence since 2008. Sigrist studies various factors within the cluster, including the architecture of synapses. Without these contact points for transmitting information between nerve cells, clear thoughts would be impossible.

The building blocks that make up the contact points between our nerve cells in turn are proteins. That means proteins are presumed to play a crucial role when the human nervous system and brain do not work as they should. To investigate these connections – or, more precisely, the individual protein components – in greater detail, Sigrist has to press ahead into dimensions that a layperson might find unimaginably tiny, working at a scale of just a few nanometers (one nanometer equals one-millionth of a millimeter). He is aided in this process by an invention from the 2014 Nobel laureate in chemistry, Stefan Hell, with whom Sigrist has worked closely for years.

Hell, a physicist and the director of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, in Göttingen, received several prizes for his groundbreaking development of stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy. Hell succeeded in developing an ultra-high-resolution fluorescence microscope that allows researchers to see down to the tiniest structures. One of these microscopes is present at a lab operated by Charité – the joint medical school of Freie Universität and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin – where some of the approximately two dozen researchers in Sigrist’s working group spend most of their time. The cost of buying the microscope: approximately 800,000 euros.

Biochemist Uses Super-resolution Microscope for Research

Sigrist first used Hell’s development in 2006, to investigate the Bruchpilot protein in fruit flies (Drosophila) – and confirmed that Hell’s technology had opened new doors for biological research. The fruit fly, which is just a few millimeters in size, is a common model organism used in genetic research. It is also ideally suited to Sigrist’s work. As he said, “Fruit flies have an astonishingly highly organized nervous system – it’s just that everything is much smaller than in humans, so it is much more accessible in experimental terms. Aside from that, many generations can be bred in a very short time.”

If the level of the Bruchpilot synaptic protein present in the fly as an organism is lowered, the fly crashes in flight. “This allows us to draw conclusions about the role that Bruchpilot plays in human nerve cells, and ultimately also in neurological disease,” Sigrist says. He explains with enthusiasm, “Proteins form marvelously beautiful structures – but STED microscopy is what makes it possible for us to take a close-up look at this architecture in the first place. Suddenly we can see ring-shaped structures and threads where there were merely dots before. This makes it possible to do things like directly tracing the transport channels of neurotransmitters.” Transmitters are the biochemical messenger substances that transmit the stimulus from one nerve cell to the next at the synapses.

Years ago, when Hell and Sigrist struck up a conversation during a dinner among colleagues – Sigrist was the head of a junior research group at the Max Planck Institute in Göttingen at the time – they soon discovered a shared passion: teasing out the last secrets from even the tiniest levels of cells and molecules. Says biochemist Sigrist, “That meant it was a logical step for us to work together and for me to test and apply Stefan Hell’s developments in biological research.”

And because there are still so many scientific puzzles to solve, their collaboration is set to continue into the future.

Further Information

- Professor Stephan Sigrist, Institute of Biology, Freie Universität Berlin and NeuroCure cluster of Excellence, E-Mail: stephan.sigrist@fu-berlin.de