Scope and structure

From their beginnings, projects such as the IEIW MA face a dual task. On the surface, they are charged with the development of suitable formats for a program of academic study. This is a familiar enough undertaking for an educational design challenge. In basic terms of project management, this requires the production of an interdisciplinary curriculum with corresponding assessment formats, whose academic and professional relevance offers value for participants recruited from various educational backgrounds.

If technological innovations such as blended learning are part of the initial list of requirements, early decisions about the role and function of e-learning within the program are crucial so as to enable program access and distance learning in fragile contexts with the help of digital technologies. Pedagogical innovation and, where necessary, an experimental approach to instructional design, complete the list of conditions needed to address the development goals underpinning the higher education agenda and the expected socio-political and economic instability in the target region.

Yet project parameters do not grant the entrepreneurial freedoms of a start-up venture for meeting these complicated demands. As an organizational unit within the research department of a degree-granting university, compatibility with established administrative processes and the material infrastructure of the surrounding organization remains imperative throughout. A second design challenge therefore concerns the sub-structures of project management and the development of suitable workflows for internal administration while providing transparency for external governance.

This handbook complements the evaluation of project out-comes by describing processes and insights that shaped these two designs: a technology-supported learning arrangement and its administrative foundations. The heuristic principle used to structure this study attempts to balance practical usefulness with conceptual clarity. This principle is described in this section in some detail, not only because it will help the reader navigate the report. The conceptual structure presented here is one of the salient insights gathered from the IEIW project, and it may therefore prove useful in the future as an analytical lens for the investigation of endeavors with similar aims.

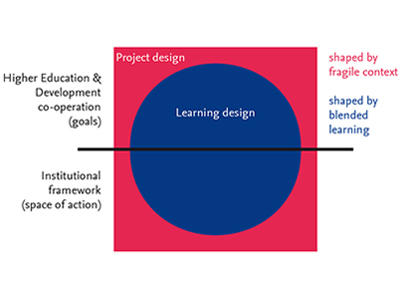

Figure 1. A blended learning format for fragile contexts consists of two design tasks.

On the face of it, the learning design challenge is a typical example for the use of educational technology in exten-ding the availability of higher education into fragile contexts. Blended learning was conceived by the IEIW founders as supporting activities in unfamiliar political, cultural and social constellations and in unfamiliar pedagogical territory, all of which would become accessible by means of distance learning. It should be noted that this premise did not regard the use of technology-supported learning as a replacement (or, indeed, a cost reduction) for conventional formats of academic learning. Instead, a set of digital tools were to be selected and tested for expanding the effective reach of quality post-graduate teaching formats and the preparation of corresponding cognitive skills in students. The emergent learning design encompasses interlocking instructional formats and assessment strategies. Its description illuminates success factors for pedagogical aspects of blended learning solutions that are not limited in application to fragile contexts.

For such an exploratory foray into a fragile political context to succeed, numerous demands from partners and participants in the target region had to be translated into processes that were compatible with the landscape of German higher education. The project team therefore needed to continuously examine, consider and adjust its own administrative and academic practices, so as to provide a locus of stability for all involved stakeholders in light of a constantly changing environment. Destabilizing factors beyond the team’s control included political conflicts in the Middle East, unsteady sources of funding, growing bureaucratic demands for compliance, contractual changes and staff fluctuation, to name only the most salient ones.

Technological innovation plays a subordinate role at best in this part of the design process, which is best understood as a challenge in project design. The key hurdles to be solved here, in other words, are independent of the digital learning components of the program. They would have required solutions all the same for an on-site program without such an online component, because the decisions are relevant to effectively and efficiently bridging two educational contexts with different degrees of robustness. Inputs and outputs on both sides of institutional and cultural gaps must be made to match with maximum possible efficiency under conditions of high uncertainty.

Accordingly, the resulting project design is traced separately from the learning design (see Figure 1), as a complex bundle of communication practices that serve to translate, negotiate, buffer and sometimes intentionally obscure the contradictions between these two contexts. For the overall project strategy to succeed, the goals specified in stakeholder agendas must be operationalized within the existing frameworks of higher education both in Germany and the Middle East. Their combined formal and informal practices both enable and constrain the available space of action.

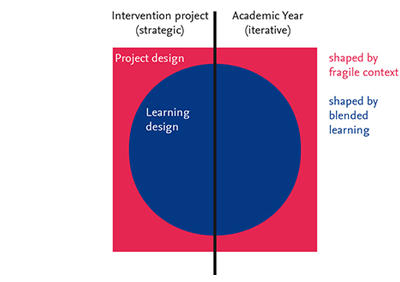

Figure 2. Both designs must conform to stakeholder agendas and operate within given institutional frameworks.

Requirements for both learning and project designs typically include external criteria and constraints that can be grouped onto two separate planes. In Germany, an ongoing federal-level strategy seeks to integrate efforts of higher education stakeholders and international development agencies for sustainable regional interventions. This cooperation was fundamental to IEIW funding and imbued the project with separate agendas promulgated by two different sets of stakeholders. The program was to transmit to students a combination of specialized disciplinary knowledge, that is to say, the basics of high quality academic research, and the generalized cognitive skills of a state-of-the-art graduate program to help increase the employability of alumni by qualifying them professionally for the nonacademic labor market.

The host organization for the IEIW program is a large research university with extensive internationalization experience, in order to provide academic supervision and the necessary infrastructure. The funding agencies charged with project supervision and the university research unit, on whose subject matter expertise the grant proposal relies, typically have neither the mandate, the capacities for the operational management of a degree program, nor the ability to award students a graduate degree at its completion. Therefore the natural implementation structure is a suitable departmental entity at a degree-granting institution, generally associated with a disciplinary chair. Implicit in this hosting structure is the compatibility of the project design with the procedures and configurationsof the educational system and the surrounding university structures, which are not especially conducive to even less-than-radical innovations due to their institutionalized organizations and procedures.

In order to have any chance of success, the project must carve out its own space of action to maneuver within the existing expectations of the institutional framework and the organizational arrangement of the project’s environment (see Figure 2). As an internal unit of the overall organization, it is subject to the densely regulated framework, compliance codes and institutionalized expectations of the higher education landscape. As a designated test bed for innovation, the project may claim a certain degree of leeway. Project managers must actively attempt to exempt innovation and experiments from some of the university’s standard routines and the educational system’s institutionalized rules. Yet inherent structural tensions between the imperatives of innovation and compliance constrain the available space of action and shape the resulting designs.

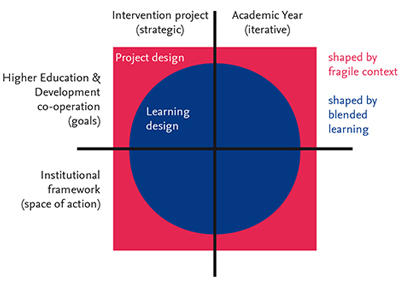

Figure 3. Academic program iterations generate data for the strategic optimization of learning practices and project structures.

A second analytical distinction between the learning design and project design concerns time horizons. Launching the initial pilot iteration of a study program in a relatively short time necessitates a number of decisions that are largely based on assumptions. Even before the pilot is completed, experiences with the first cohort of instructors and students generate data points to adapt and improve design. Future iterations of the program, implemented here over the lifetime of the project from 2013 to 2019, have each been able to draw on a growing set of empirical findings.

Refining and adapting a learning design through multiple iteration cycles is typical for educational formats. Experienced instructors are able to facilitate learning with consideration of the actual students in the program by drawing on a set of available instructional theories. In the case of the IEIW Master Degree, however, both faculty and students were recruited anew for every single cycle, in order to involve a broad set of interdisciplinary specialists. For this reason, iterative learnings and improvements could not be captured, documented and applied by faculty, but such tasks were assumed by the project team instead. We must therefore distinguish analytically between the team’s role in operational support during each 12-month cycle of the degree program and its attention to maintaining and adjusting overall project strategy and formats.

The usefulness of distinguishing strategic and iterative perspectives is not limited to the learning design. It similarly applies to the design of project management and administration. The diversity of backgrounds of students from fragile contexts by definition results in an administra-tive overhead, from enrolment to graduation, which defies standardization into bureaucratic routines. This challenge is rooted not so much in the unique student biographies – although these are a contributing factor – but in their general lack of familiarity with the formal rules and informal practices of attending a German university, albeit from a distance. Students in an on-site program are able to acquire this understanding during their first weeks and months of interaction on campus. Students from fragile contexts in an international distance learning program must bridge, not only geographic space, but substantial cultural gaps for the same learning outcomes, which are often further impeded by a language barrier. The same thing is true from the perspective of the host university, its structures, practices and staff. Regular study programs assume on-site teaching and learning, targeting students and instructors assumed to be fluent in German. The administrative framework for such a university’s academic programs, whether analogue or digital, involve documents, forms and interactions in German and presuppose (often implicitly) an understan-ding of the socio-cultural traditions surrounding and shaping the organization.

Once again, the operational tasks for the administration of each IEIW program cycle are complemented by a strategic perspective to optimize such workflows into more efficient routines over time as part of the project design (see Figure 3). The shift between the temporal arcs of operati-onal management for each iteration of the program and organizational development over the project lifetime is inevitably shaped, not by the subject matter to be studied nor the blended mode of instruction, but primarily by characteristics of the two fundamentally different educational systems involved.

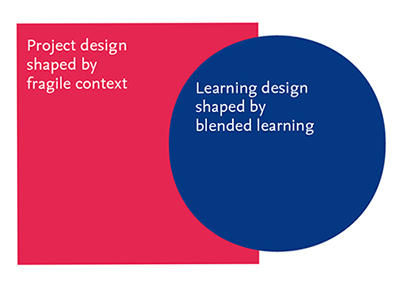

Figure 4. The analytical lens comprises four distinct perspectives on two separate design tasks.

The structure of this handbook therefore combines the two-tiered design missions entailed in the project in the analytical structure depicted in Figure 4 above. Each of the main project outcomes, a suitable learning design enri-ched by multiple iterations and a compliant project design for innovative reach into fragile contexts, is horizontally divided along the two dimensions of defined project goalsand actual action space (x-axis). The vertical line distinguishes the strategic project perspective from the operational concerns for each academic cycle of program iterations (y-axis). The two workstreams of the IEIW Master project are thus analytically split into four sections for the learning design and four sections for the project design, a distinction that may be fruitfully applied to similar.

About

» Overview

» Scope and structure

» Format and user guide

↑ top