1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

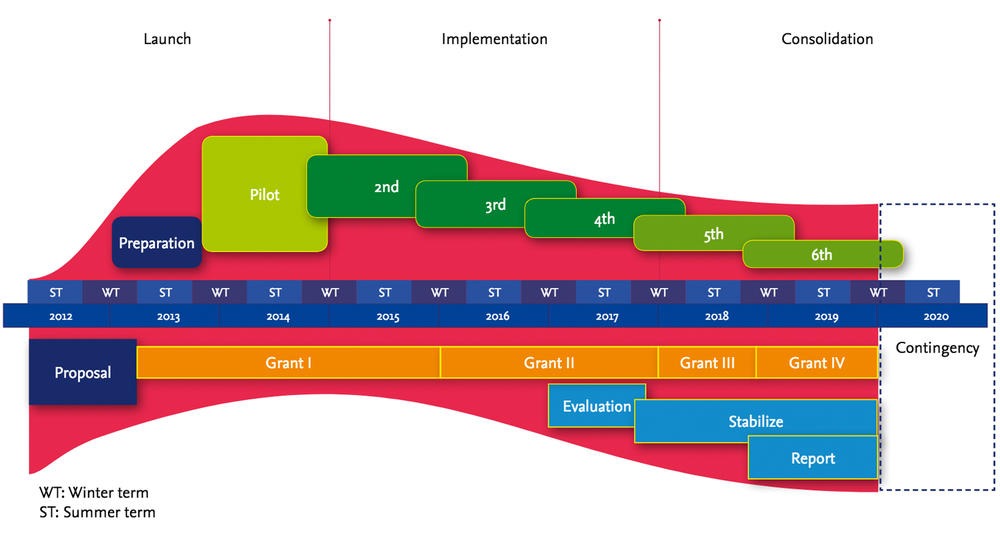

Figure 6. Over the entire project duration, the workload for administrative staff shifts between the academic program iterations and the strategic project perspective.

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

Introduction: Stakeholder goals and strategy

The MA “Intellectual Encounters of the Islamicate World” (IEIW) was proposed as an online learning pilot project within the Department of History and Cultural Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin (FUB). Starting in 2013, the Ministry for International Cooperation and Economic Development (BMZ) granted the first installment of what would later become seven years of federal funding, so that a cohort of 20 graduate students could immerse themselves into an online course centered on a subject that was academic indeed.

Advanced graduate studies in medieval theological history offer a prime example for a highly specialized area of research. Scholars in this field are acquainted with each other on a first-name basis the world over; their conferences are comfortable, frugal affairs in smallish venues. In Germany, only a handful of university departments offer the subject as a degree program, in part because the philological field has never recovered from the Nazi regime’s catastrophic assault on its thinkers and traditions. At any given location, the active student population enrolled in courses on this topic numbers in the dozens at best. Those choosing to commit to its study long term are a modest crowd in more than one sense, because career opportunities for this kind of specialization continue to be sparse. It is all the more surprising, then, that the stakeholders underwriting these funds clearly reasoned with quite a utilitarian mindset.

Educational technologies had become wide-spread and affordable by 2013. Mobile devices could be made available in the Middle East region more easily than access to physical leaning infrastructures; sufficiently stable internet bandwidth already existed. Emergent interactive formats of digital learning, having come a long way from earlier passive web-based training formats, would allow interactive mentoring and personalized feedback for successful learning outcomes and help maintain high academic standards.

Thus digital distance-learning technologies could provide efficient access to a reputable master’s degree for English-speaking students in the Middle East, especially for Palestinian students in the West Bank and similarly fragile contexts. The online learning program would enable participants to surmount geographic, financial and socio-political hurdles that had prevented them from attending a similarly rigorous graduate program on-site at local university campuses. Program alumni and their future employers could be assured that their degree courses satisfied the rigorous academic standards of excellence provided by a preeminent German university of international renown.

No less instrumental a view of the subject matter was taken. Students would ponder the intellectual exchange among three historic world religions that, on the one hand, produced an incredibly rich corpus of philosophical and scientific thought for historic study, and on the other hand continues to shape national borders and political conflicts in the region today. This kind of education would equip future professionals from all sides with skills and the capacity for engaging in intercultural dialogue. Their enrolment in a program for the study of cultural history would effectively immerse them in methods of intercultural discourse with theological scriptures. Furthermore, a carefully balanced composition of the student body and the immersive quality of study would simultaneously foster constructive discourse among a diverse cohort of contemporary fellow students from Israel, Palestinian territories and Germany.

The resulting project is holistic indeed, but it is also quite intimidating in its reach. One could consider ambitious the higher education goal of launching a state-of-the-art graduate studies program with international visibility in a humanities niche, whose success requires a small but steady stream of skilled applicants with a working knowledge of both English and Arabic, interested in medieval theology. Surely worthwhile on its own would be the development goal of providing access to a career-enhancing academic degree program and to equip future professionals in the Middle East with intercultural training. To these dual tasks, add the innovation challenge of designing, producing and operating a one-year master program as a distance-learning program, built with primarily digital learning materials and relying on predominantly online interaction, while at the same time controversial discourse on the merits of “digital humanities” has been dampening enthusiasm for technological experiments in the field.

The divergence of stakeholder agendas is obvious even from this brief of a sketch. This discrepancy would inevitably require trade-offs among the multilayered set of potentially conflicting goals. From the outset, the project scope encompassed so many dimensions that spectacular failure was actually unlikely in light of its multifaceted complexities and multidimensional goals. Various stakeholders would have noticed, of course, if the project failed to reach specified indicators. Yet the various aspects of experimental design and innovative instruction formats were so closely intertwined, and the number of predetermined breaking points was so large, that a gradual and quiet extinction of the program probably would not have surprised any of them. This section describes how the degree of freedom and flexibility necessary for true innovation arose from an entanglement of goals at the unlikely intersection of medieval philosophy and online learning.

Research agendas and technological innovation

The impetus for the launch of a trilateral master program in co-operation of German, Israeli and Palestinian universities to support and foster intercultural dialogue arose from a joint research initiative. Professors Sabine Schmidtke, Sari Nusseibeh and Sarah Stroumsa, three scholars of medieval religious and cultural history, were at the time based at the Freie Universität Berlin (FUB), Al-Quds University (AQU) and Hebrew University Jerusalem (HUJ) respectively. After having collaborated for several years, they began to investigate the outlines for a joint field of research. From 2008 on, their ground-breaking interdisciplinary research of the Islamicate world, shared with graduate and postgraduate students, had taken center stage over the course of several symposia, workshops, research papers and summer schools.

Originally coined by the historian Marshall Hodgson in 1947, the term “Islamicate world” describes social and cultural aspects arising from an Arabic and Persian literate tradition that can be found throughout the Muslim world and is not directly linked to the Islamic religion1. The concept delineates a socio-geographical expanse from Andalucía to the Hindukush Mountains2, where commonalities of language and religion created a contiguous social space, making the fluid interchange of theological, philosophical, legal and scientific ideas the norm rather than the exception (see Figure 7 in Chapter 2).

These foundational activities congealed into a small artifact, which would grow into a building block for developing the IEIW program. As befits the current century, this inchoate foundation took digital form. In the summer of 2009, technologically knowledgeable organizers of a Marrakesh research workshop created a proper homepage3 with the goal of providing participants with preparatory materials, an opportunity to interact remotely and to capture research progress as well as results. This humble digital artifact supplied a virtual framework for studying the intellectual and multicultural legacy of the medieval Islamic world. Intended first and foremost as a virtual library, the website made publicly available numerous medieval philosophical texts, along with a broad array of research tools.

From its inception, the two-fold intention of this platform was to highlight interconnections among medieval thinkers and to foster both interdisciplinary research and increased cross-cultural understanding for modern day audiences. In the words of one of its authors, the platform could become a seedbed for “growing an international community of scholars, students and educated lay readers, dedicated to studying these philosophical works comparatively, who wish to engage in an ongoing discussion about them.” Its initial function was as a study tool for a week-long workshop in Marrakesh at the end of the academic year for students and faculty enrolled in four parallel courses on the intellectual history of the world of Islam taught at Bar-Ilan University (Jerusalem), al-Quds University (Jerusalem), Tübingen (Germany), and Yale (United States). The website’s basic interaction features were then used to capture results of the workshop, helped participants stay in touch and created visibility for the research framework that would attract outside interest. Recognizing the potential of the growing movement of open education for their scattered field, the researchers responsible soon afterwards turned their online content repository into an “Open Educational Resource” (OER). The content was thus made available without licensing fees for educational and research uses beyond its original purpose.

This decision marks an important connection between innovative transdisciplinary scholarship in a humanities niche with the global macrotrends of digitalization in higher education. In Europe and North America especially, digital network technologies continued to penetrate higher education at an increasing rate, largely driven by access to internet-enabled mobile devices and consumer broadband. Similar but more selective trends could be observed globally, with some regions in the Southern Hemisphere “leapfrogging” technological steps such as broadband-connected PCs in favor of internet access on smart mobile devices, but there was also a deepening “digital divide” between social strata with access to such infrastructure and those without. The open education movement took these trends as a starting point for its focus on content rather than technologies. It argued that making educational resources, especially those created with public funds, freely available digitally would lower the threshold for access to high quality educational content. Concurrent with the timing of the Marrakesh workshop, open education was being adopted by numerous prestigious universities as a sustainable approach for broader access to higher education worldwide (cf. Heise, 2018).

Manuscript 2016, Foto: Wannenmacher

Having linked small-scale innovation in a community of scholars to the large-scale innovations of digital educational technologies, Professors Schmidtke, Stroumsa and Nusseibeh required only a short leap of entrepreneurial imagination for the next logical step of academic entrepreneurship. The technological promise of dissolving the formal boundaries of educational institutions and nation states4 could effectively be harnessed to the similarly transcendent approach of interdisciplinary study of the Islamicate world. Much of the newly discovered historic source material was being made available to researchers all over the world in digitized form. Leveraging channels for online interaction would broaden access from a small community of scholars funded through research organizations and philanthropic grants to students interested in the newly emergent field.

In brief, the idea of the program’s initiators was to conceive, develop and pilot an online program, with an almost unprecedented degree of cooperation between various stakeholders within the German landscape of development, foreign policy and internationalization, in order to achieve a quantifiable impact within a notoriously complicated setting. Their joint intervention sought to increase access to higher education and improve educational opportunities in a politically, regulatory and socio-economically fragile context5. It was premised on the growing realization that the combined effort of these stakeholders and a holistic approach could more efficiently leverage various resources and multiple kinds of expertise into sustainable, more impactful outcomes.

The notion of open education explicitly aimed at inclusion across socio-demographic strata, especially relevant to those students belonging to marginalized groups within the political climate in their home region or excluded from higher education due to a lack of local opportunity. These technological means entailed the promise of removing constraints to professional training especially for Arabic-speaking students from the Middle East, namely in the fragile context of Palestinian higher education. In this notoriously complicated setting for development intervention, an audience of future leaders could benefit immensely from access to high quality educational programs independent of the participant’s particular passport, living situation, personal faith, family tradition or precarious income.

An opportunity for development intervention

To advance the visibility and impact of a small emerging research field, an international graduate program is the natural organizational form. It can attract and instruct junior researchers in the concepts and methods suitable for scholarly investigation. Relationships within the tight-knit community of experts associated with activities of a research agenda can be leveraged into teaching commitments. Instruction, mentoring and guidance can thus be provided by renowned instructors who count among the leading voices in their respective fields, to the benefit of students. The proposition of an interdisciplinary, trilateral program for historic study of the medieval Islamicate world was therefore a logical step in the development of the corresponding research unit at FUB.

The cooperation among the three founding scholars and their respective home universities to pursue the idea of a joint master’s degree could have followed the previously established pattern of bottom-up research and teaching activities. Instead, in 2013 a window of opportunity presented itself for quickly creating and funding a master program within a rather short period. At that time, geopolitical signs for the peace process in the Middle East were pointing in a hopeful direction, implying at least a sufficient degree of stability in the foreseeable future to engage in socio-economic development. For Palestinian students, access to internationally respected higher education and the associated academic rigor at graduate and post-graduate levels had been severely constrained. More specifically, a humanities program with a focus on medieval philosophy was completely unavailable to them locally. Within German development and foreign policy interventions, educational initiatives in the Palestinian region have overwhelmingly focussed on technical subjects with practical applicability in the immediate context so as to avoid the risks of regional brain drain.

Arguably then, a program of advanced studies concerning the conditions of peaceful intercultural dialogue, albeit concentrating on medieval history, does have practical development application in the region’s conflicts. A master’s degree in the humanities from a prestigious German university can prove to be a career catalyst for Palestinian students, helping those from marginalized backgrounds in the West Bank and Gaza especially to prepare themselves for senior leadership positions. Therefore, offering an advanced education and qualification program with a strong emphasis on intercultural dialogue was an idea that resonated in the community of various institutional stakeholders. With the help of emergent technologies for teaching and learning as an enabling condition for access to a fragile region, providers of higher education would enable stakeholders of regional development to intervene for the educational benefit of a population difficult to reach by conventional means.

In terms of finding a host organization, the IEIW Master program could become an organic extension of the corresponding History of the Islamicate World research unit6, which had been well established within the FUB History and Cultural Studies Department for several years. The cluster would provide a third-party buffering organization to create a partnership setting for institutions both on the Israeli and the Palestinian sides of a trilateral cooperation. Through collaboration with FUB’s prominent in-house expertise with e-learning, it could provide the infrastructure, expertise and support for the launch of an online study program. Finally, FUB had an established track record of international study programs, research excellence, and access to dedicated funding sources for addressing the target region.

It was also necessary, however, to position the MA program in a way that would make it attractive to the participating universities as well. It was reasonably hypothesized that this could be achieved through the creation of a prominent international research collaboration with an emphasis on studying primary texts in the original Arabic. The intercultural approach to advanced studies in the history of religious and philosophical ideas could bring international visibility and potential political goodwill. Graduates would have acquired a thorough understanding of the deep links between Muslim, Jewish and Christian thinkers in the Middle Ages. The conflicted atmosphere and the political visibility of Israeli and Palestinian universities make formal partnerships notoriously difficult. Nevertheless, at least in terms of strategic incentives, a trilateral cooperation between the three participating university departments in Berlin and Jerusalem could be envisioned as a long-term organizational backbone for the IEIW Master program.

Thus, it was an ambitious but not outright impossible working assumption that governance for a joint graduate research setting could be situated within a formal co-operative framework among the three respective partner universities. It later turned out to become a foundational challenge, and serves as an example the first of several important learning occasions. Not even a subject as historically distant as the investigation of intellectual exchange during the medieval era is able to escape the conditions of the present environment. The structures and practices shaping the program’s design are inevitably bound up in the political, social and cultural frameworks of modern-day human geography. As soon as the political window of goodwill that had enabled the partnership closed and more aggressive stances were taken by the conflicting parties in the Middle East, the institutional partnership became strained. At one point, a complete boycott of the program by Palestinian institutions such as the AQU threatened to derail the entire program until this situation could be compensated for by a more informal framework and additional efforts of the remaining partners.

The obvious lesson here pertains to a close examination of the assumptions underlying such stakeholder cooperations. If institutional structures in the targeted region create fragile contexts for marginalized groups, they represent deeply entrenched cultural norms that deny access to these groups based on criteria such as religious faith, notions of ethnicity or simply poverty. The point is that political and educational institutions are not necessarily fragile in themselves, they can be quite rigid in fact, but they produce fragility in the life-world of those excluded individuals. By the same token, these institutions cannot unfortunately be relied upon to provide stable partnerships within international collaborations aiming to alleviate this intentionally created fragility for local student populations.

Higher education access in fragile contexts

In 2013, the initial IEIW project proposal outlined the dual project objective as increasing access to a state-of-the-art academic education and providing advanced intercultural skills training in the Middle East. It proposed the creation of a 12-month, consecutive interdisciplinary blended-learning master program for a cohort of a maximum of 20 students from the Palestinian territories, Israel and Germany in a ratio of 2:2:1. The experience of jointly studying and researching the intellectual roots of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, particularly their closely interwoven development up to early modern periods, sought to provide professional instruction and to introduce a level playing field for intercultural dialogue among all the participants.

When the goal involves broader higher education access on the institutional supply-side, an obvious consideration is the actual demand within the target audience and its ability to take advantage of newly created higher education opportunities. Requiring participating students from the Middle East to reside in Germany for the duration of the program would have been prohibitively expensive. More importantly, even if such a stay had been possible, it would probably have reduced the accessibility precisely for those marginalized groups that the program was attempting to reach. The potential benefits of using e-learning formats and technologies of distance learning consisted precisely in offering access close to the life-world of participants in the West Bank and Gaza, specifically. Suitable content, instructional scaffolding and reliable assessment formats could be provided remotely, relying on the availability of a sufficiently stable network infrastructure and consumer-grade private computing devices. Networked digital technologies could create the kind of communicative networks among students, scholars and universities – each with their own backgrounds – that would enable constructive dialogue across national borders, political and religious lines of conflict and segregation.

From a funding perspective, the sizable digital component was a helpful ingredient to position the program as a markedly innovative format that could help exploit the potential of these technologies for higher education. With regard to online education, it is an open question, in the German context in particular, how qualities of “academic excellence” could be maintained in a graduate program of distance learning. Naturally, there was the question whether blended learning could allow the delivery of such advanced education not just to a broader audience, but also at a lower cost compared to conventional formats of on-site instruction. The project could thus contribute insights into the potential use of technology-enhanced learning in furthering the political goal of internationalization in German higher education, with an exploration of instructional formats in the growing area of the digital humanities.

The IEIW proposal emphasized that the program did not claim to provide ready-made solutions toward training intercultural skills with nascent Israeli-Palestinian civil society. Instead, it considered any such progress toward the foundation for mutual respect as emerging from shared activities in direct approximation of each other as part of a diverse learning cohort. An explicit reference model was the “West-Eastern Divan Orchestra7” for young Israeli, Palestinian and other Arab musicians, founded in 1999 by Edward Said and Daniel Barenboim. In sum, the IEIW Master Degree proposal posited that learnings from such demonstrated achievements in civil-society building via joint engagement in the performing arts could be replicated in a graduate academic setting. The participation of Israelis and Palestinians in the graduate studies was not an add-on feature, but could be justified by methodological and pedagogical considerations alone. From the higher education perspective, therefore, the intended development outcomes in fragile contexts were desirable and worthwhile side-effects, but they related to considerations of the project design such as recruiting, funding, degree-granting, not to the learning design of the proposed graduate courses.

West-Eastern Diwan Musicians, Foto: IEIW

The initial funding tranche was the first of four consecutive grants, subject to continuous quality monitoring and externally conducted evaluation for continued funding in 2016 through 2019 (see Figure 6). During the evaluation cycles, the notion of fragile contexts, which the original proposal had mentioned only in reference to the politically instable situation in the Palestinian territories, became increasingly prominent. The use of the term “fragility” was an outgrowth of dealing with “failed states” in foreign policy and development settings originally referring primarily to state structures and governmental activities in those political contexts in which the state has only a limited monopoly on the use of force, cannot provide even the minimum of basic social services, and whose institutions lack legitimacy (OECD, 2013, 2015). Meanwhile, “fragility” has become more broadly applied in the parlance of German foreign policy and development programs, now including socio-cultural aspects of instability for marginalized social groups outside of state structures.

In education and training programs, the term is used to draw attention to the socio-economic dimension affecting the livelihood of such groups, taking account of factors contributing to fragility such as a lack of validity in private contracts, a lack of stability for social norms, a lack of legitimacy for educational organizations and an inefficient allocation of human resources (cf. Binder & Weinhardt, 2014). Such an understanding comes closer to describing, albeit in simplified terms, the situation of Palestinians affected by fragile circumstances in spite of institutionalized state structures on both sides of the conflict and a more or less stable provision of social services. An appropriate shorthand description of “fragile contexts” must capture living situations of marginalization and precariousness that afflicts only segments of a given local population due to ethnic, religious or other factors, as put forward more recently (Mcloughlin, 2016).

The breadth of the latter, most recent definition implies that only holistic approaches that cut across separate policy spheres and stakeholder agendas can deliver effective development and training for these groups. The IEIW grant application was somewhat ahead of this discourse when it outlined the creation of just such a holistic intervention without active use of the fragility concept in 2013. The master program it proposed to implement was to address a fundamental deficit in the regional educational landscape of the Middle East, to introduce and maintain rigorous academic standards to provide access to high quality instruction, to contribute to social cohesion by virtue of educating future professionals’ intercultural skills, and thus ultimately to have a long-term impact on the continuing efforts supporting the peace process.

Additional benefits were to accrue on the supply-side of the equation, furthering the internationalization and modernization of the three universities involved through academic partnerships, knowledge exchange and the use of digital technologies while advancing a promising field of interdisciplinary research.

Notes

- See https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/islamicate-society for details.

- For a helpful dynamic map of the various expanses of the islamicate cultural sphere over eight centuries see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I14x4-q_Gj4

- The site itself was taken offline in 2018 as outdated. Curious readers may access cached versions using the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20100908225704/http://www.intellectualencounters.org/.

- To their credit, academic founders and institutional funders of the IEIW Master made this connection well before the subsequent hype-cycle related to digital “disruption” of higher education in the wake of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) in 2012ff.

- The notion of “fragile contexts” is not limited to aspects of the state and legal insecurity, but refers to a broad set of socio-economic indicators of instability that particularly affects socially marginalized groups (Binder & Weinhardt, 2014; OECD, 2015).

- Background documentation of the Islamicate World research unit at FUB, directed by Prof. Sabine Schmidke, is available at http://www.ihiw.de/w/workspace/uploads/publications/brochure2.0_web.pdf

- For details see https://www.west-eastern.divan.org

References

- Binder, A., & Weinhardt, C. (2014). Berufliche Bildung in fragilen Kontexten. Berlin: GPPi.

- Heise, C. (2018). Von Open Access zu Open Science. Lüneburg: meson press. http://doi.org/10.14619/1303

- Mcloughlin, C. (2016). Fragile States. Birmingham: GSDRC, University of Birmingham, UK. Retrieved from http://www.gsdrc.org

- OECD. (2013). Think global, act global. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2015). States of Fragility 2015. OECD Publishing.

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top