8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

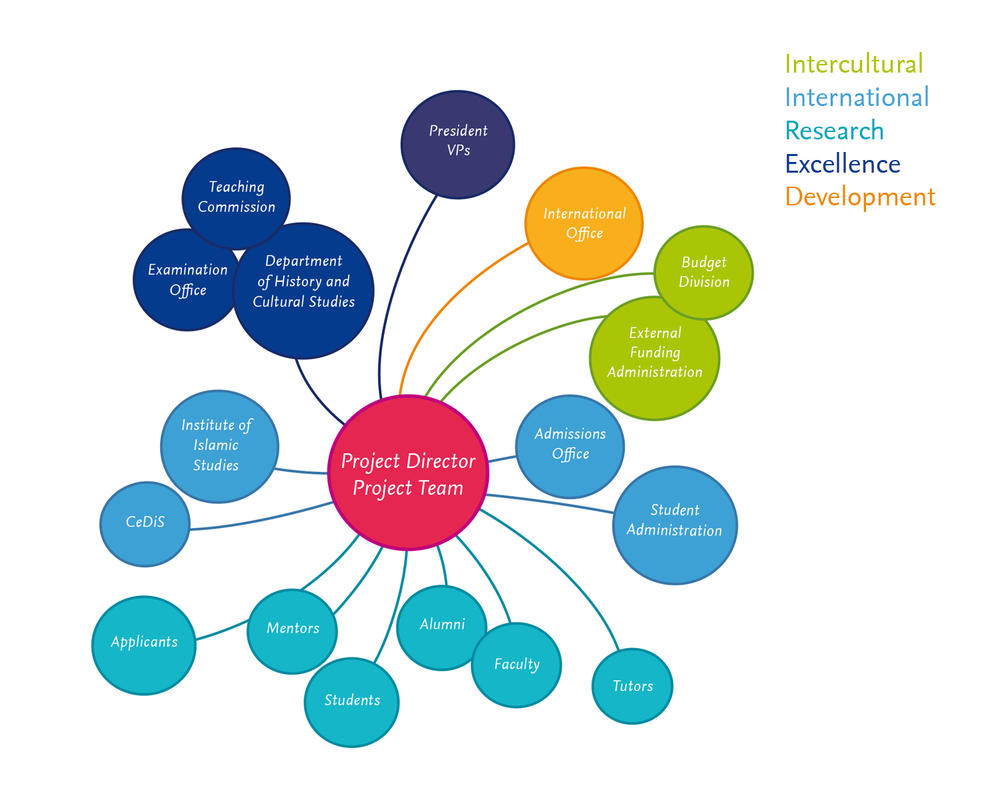

Figure 14. Multiple rationalities require translation and buffering strategies.

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

Introduction: Governance for wicked problems

This section on innovation and compliance presents the tensions between an initiative fueled by optimism, persistence and academic creativity and an environment that is heavily regulated and structurally resistant to change. Just like the proverbial bumblebee seems to defy the laws of physics, the initial founders of what later became the IEIW Master program had faith in the merits of an idea. The first sketch of their vision was outlined in a short letter to a potential funder – a letter that was written, but never in fact sent.

The aim of this report has been to abstracts salient aspects of the IEIW Master program in the form of general principles. They are presented not as best practices to be emulated, because their manifestations in this particular project are deeply intertwined with their respective contexts. They may be teased out analytically, but their concrete results can hardly be taken at face value and transferred identically to a different setting. But it is hoped that they can serve as guiding principles for design decisions relating to other fragile contexts requiring an agile mindset and adaptive workflows.

Publishing this handbook in the hybrid format of a printed linear document on the one hand and a loosely related connection of digital content on the other underscores that it is not intended as a blueprint. The activities and design decisions documented here cannot ultimately be removed from their respective contexts, as they are bound up with the political and technological state of affairs at the time of their creation (and this writing). The intended usefulness for funders and practitioners of similar projects in fragile contexts is that of a resource for empirically grounded guidance during the conception, implementation and evaluation of such ventures. It may serve as a general reference point for strategic initiatives and co-operations to align stakeholder expectations and criteria with the factual realities in the Middle East and similarly fragile contexts.

All involved stakeholders ignored the solid and serious reasons that this idea should not take flight. They hypothesized an entrepreneurial opportunity. Technologies were becoming available that would remove or at least reduce geographical obstacles and allow for the creation of something heretofore impossible: A study program for intercultural and inter-religious dialogue that focused on joint enrollments of students from cultural spheres of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, explicitly including Israeli and Palestinian participants.

In a truly entrepreneurial spirit, their aims were anything but modest. From an academic perspective, the founders attempted to construct a research agenda and shape a field of academic inquiry in the humanities. From an educational perspective, the project goal was to provide world-class training in intercultural and inter-religious dialogue for a generation of professionals that amount to relevant real-world career skills. From a development perspective, funding agencies targeted opportunities for technology-enhanced education and training to marginalized groups in a conflictual, politically unstable world region. Taken together, these multiple agendas and their both ambitious and partially conflicting objectives amount to a near infinite list of reasons for immediate grounding of the bumblebee project.

As their story makes clear, many of the apparent obstacles at the beginning of the undertaking in fact turned out to be enabling conditions that gave the project its ultimate shape. Positioning itself in such an unstable, marginal space - outside of established research traditions, experimenting with emergent digital formats and addressing students in a fragile geographic region both created the necessary room to maneuver and exempt the project’s creation and scope from established expectations, making innovation possible.

This section describes the governance mechanisms of the project inside its university environment. Because the IEIW project addresses a „wicked problem“ (Dentoni & Bitzer, 2015) that encompasses a multitude of incommensurable variables across various dimensions, it is impossible to administrate and govern according to the conventional top-down logic of project management. Instead, the unifying organizational principle behind both the instructional design and its administrative foundation in project design are the methods and the mindset of agility.

Virtual faculty and material impact

With the introduction of the Bologna reforms in 2006, the calculation of student capacity for a university and teaching load per student has devolved from the interstate level to decision-making of state ministries. This has allowed states to depart from a system of teaching loads standardized by discipline (Curricular Norm Value, CNV) and instead consider local conditions for calculating student teaching loads and faculty capacity on a per-program basis (Winter, 2013).

The instructional quality that departments with a historic-philological focus at German universities were able to provide had suffered especially from the rapid rebalancing of the variables used for calculating teaching load and faculty capacity (Herbert, 2008). A CNW value lower than in the humanities is only applicable to Law programs, where it has been deemed so low as to be unconstitutional due to a violation of equal conditions clauses (Würtenberger & Fehling, 2000). The politico-bureaucratic illusion that the size of a lecture can be increased to the practical if not the theoretical maximum without any loss of quality in teaching thus appears to have collapsed. Meanwhile, the humanities continue to be underfunded, yet their caché is growing in terms of employability. Learning outcomes in what can broadly be called the liberal arts field have been shown to generate positive outcome on intercultural effectiveness, inclinations to inquire, lifelong learning and leadership, independent of student background characteristics and institution attended (Seifert et al., 2008).

The blended learning format allowed the History and Cultural Studies department in Berlin to circumvent these standard indicators for student-teacher ratios and assemble a virtual faculty of renowned researchers, each a distinguished expert in their field, to teach a highly motivated group of students. Considering the vintage character of the subject matter, where the research community is thinly spread across the globe, this is not the trivial feet. Without this virtual faculty, the department would have been hard-pressed, and probably proved unable, to offer a sufficient roster of instructors steeped in the relevant field to justify similarly specialized on-site program.

The ability to invite every year anew scholars with the most recent and most relevant research activities further assured that teaching would be steeped in state-of-the-art methodology and up-to-date inquiry. Crucially for an emergent, interdisciplinary subject, the selection of docents from experts in different scientific disciplines and their corresponding methods benefits not only the breadth of the educational program, but as a side effect creates a secondary benefit: Continuous variation of perspectives and approaches on the subject matter is an opportunity to sharpen the fuzzy contours of the overall research agenda and thus contributes to the development of the field itself.

Session, picture: IEIW

Intercultural learning goals of the program could be supported by a corresponding diversity regarding sociocultural backgrounds among faculty as well. Looking beyond individual learning units, such as a lecture, their professional relationships and communicative practices amongst each other, as well as their engagement with students, adds another performative dimension. They are, in fact, engaging in intercultural dialogue, echoing the interreligious discourses of the islamicate world they are studying. It matters, in other words, not just what they teach, but how they teach it. Students could experience directly the possibility, the validity and the benefits of intercultural dialogue that was practiced by their teachers.

The e-learning lecture and seminar formats enabled practically all interested instructors to participate in the program, because it offered precisely the kind of spatial and temporal flexibility inherent in digital technology that an equivalent on-site program is unable to replicate. There was no need to apply for leave of absence at their home university, no travel arrangements were necessary, no residency at the hosting institution in Berlin had to be arranged. The threshold for their active participation was lowered significantly by the online nature of the program.

The fundamental notion of higher education access, which the online learning format offered to students from fragile contexts, equally applies to the instructors as well. For them, it is the very stability of their environment, whose rigidity would under conventional circumstances impede or limit their ability to participate in the project, in other words: their action space. Their use of e-learning opened up the space and provided the necessary flexibility that enabled their participation.

From the host university’s administrative point of view, this flexibility translates into substantial savings, both in cost and in resources for administrative overhead. Nevertheless, because these savings result from expenditures that were never incurred, they remain invisible as savings even though they are not difficult to quantify. To measure their actual volume, in other words: the material value generated by the use of online learning, one would have to calculate the amount necessary for creating the equivalent on-site program with lecturers actually coming to Berlin.

Some efforts have been made in the recent past, to calculate the cost of on-site teaching in comparison with e-learning in the form of Massive Open Online Courses. They concentrate, however, on effectively scaling-up individual learning units such as an individual lectures for a large number of participants, to calculate per capita costs for viable business models (Epelboin, 2016). Unfortunately, no usefully applicable benchmark measure is readily available for comparing a full on-site Master program with an online equivalent, arguably because the associated investments differ substantially by discipline, duration and educational environment. Since the amount of savings were understood to be substantial by the external third-party funders of the IEIW program, the upside of „cost savings“ never needed calculation during the program duration. These cost savings remained invisible matters, though, because granting teaching assignments to visiting lecturers is an administrative decision at the departmental level with significant impact, independent of the funding source. All such guest lectureships have to be approved annually by the Teaching Commission for the overall Department of History and Cultural Studies, because they invariably increase the official headcount of adjunct lecturers and therefore the volume of teaching resources at the Department.

Core office and Advisory board

Due to the co-operative nature of the overall project, overlapping agendas of external stakeholders meant that educational, economic, political and academic goals had to be balanced in the design of the IEIW program. The network of relationships and governance within the host university is not directly susceptible to many of these goals. Departments and governance bodies tend to follow their own criteria. The responsibilities, priorities and expectations of different departments and organizational units within the university therefore demarcated a corridor of action for project parameters.

A small project team at Freie Universität Berlin has been in charge of operations at the core office throughout, under the dual leadership of an academic director and a managing director. Aside from the operational demands of administration and development, it was tasked with achieving project indicators and balancing the funding agendas. Perhaps an equally important contribution to this successful outcome can be attributed, of course, to the students enrolled in the program.

In the process of knowledge transfer and instruction, the project management team was originally conceived as merely functional, charged with program operations (recruitment, admissions, administration, compliance, reporting), but mostly invisible when it comes to subject matter and content, with the possible exception of quality assurance over time. This is in part due to the standard template for funding programs of this kind, partly due to the high degree of uncertainty regarding the final artefact when the program was first conceived.

As it turned out due to various specifics of the program, the operational team has to compensate for deficits created by the lack of state structures on the benefactor side due to the fragility of the context. Moreover, the project team also had to mediate and buffer the similarly absent structures on the side of the program facilitators, due to its ad-hoc and pilot nature.

The project team recognized early on, that the accumulation of institutionalized knowledge, that is passed on among student and faculty peer groups in a conventional program of study with overlap among the various student cohorts, would have to be documented, formalized and effectively disseminated to incoming students and faculty to achieve the desired learning outcomes during the implementation phase. Ultimately, the project team was aware of the rapid institutionalization of these pedagogic aspects essential to student learning, that program alumni were recruited to provide on-boarding and mentoring support for the incoming cohort so as to assure that the routines of „operational blindness“ would not impact these inputs negatively.

The academic Advisory Board, which consists essentially of the program founders, oversees and supervises the overall program, determines content and structure of the curriculum, interviews applicants and participates in the selection of students for admission. They are intimately familiar with the subject matter and the programs administrative workings, yet in their capacity as board members, they are not directly involved in teaching. The board instead focusses on mentoring for the overall cohort, sometimes for individual students, but mostly concerned with balance and cohesion in the student community as a whole. The Board as an organizational vehicle was created as just such a make-shift solution, as it allows program funders to continue in their duties to the project even after their respective relationship to the institution in the trilateral partnership has changed in character.

On a departmental level, the transfer of its founding scholar, Prof. Sabine Schmidtke, from FUB to Princeton University in 2014 was an immense organizational challenge and a turning point in internal governance. Yet it proved to be an informal validation of the academic qualities the program had been able to establish up to that point. On an operational level, it resulted in an unexpected organizational vacuum, as project funding and governance were tied to the departmental chair that had now become vacant in her absence. Simultaneously, the driving force behind the History of the Islamicate World research unit was suddenly diminished, due to a concomitant shift in departmental focus. The project thus existed for two-thirds of its duration without solid grounding either in an endowed chair at the department nor in the parallel activities of the research cluster. It had, in manner of speaking, become adjunct to itself.

Although a pragmatic solution for governance and oversight was quickly found within the FUB department, this organizational shift made the program’s position more peripheral still to strategic decisions at the departmental, the organizational and even the state and federal level. Similarly, the partner universities in Jerusalem had to modify their involvement in program operations and reconsider the organizational support they were able to provide, albeit for different reasons. Once the political climate in and around Israel turned more hostile, the AQU formally withdrew from the partnership in the course of 2014, as part of the broader political boycott movement of Arab-Palestinian organizations. Thus, the IEIW project ran for most program iterations with merely a fig-leaf version of the originally envisioned tripartite co-operation agreement that was supposed to be providing its foundation. The HUJI on the other hand continues to actively support the IEIW program, with high estimation for the work and the person of founder Prof. Sarah Stroumsa. The HUJI partnership plays a crucial role as a conduit and distributor for co-funding made available by the Rothschild foundation for Israeli student participants. Yet in equal measure, the IEIW effectively competes with similar graduate programs offered by HUJ in terms of recruiting academic talent. To expect the HUJI partner to actively advertise and increase visibility of the IEIW program runs counter to the local incentives of avoiding an academic brain drain.

It cannot be overemphasized, that the principal structures of the tripartite co-operation were held aloft through multiple crises by personal relationships. Strongly vested personalities within the project and a solid cadre of external advocates never wavered in lending their social, political and material support. What is remarkable to observe, in this instance, is how such strong personal connections and professional partnerships between the founding individuals, the project team and representatives of the external stakeholders proved much stronger and more reliable than the formal bonds created between institutional entities. Intuitively, one would expect just the opposite development, namely for the institutions to last and for the individuals to move on — since that is in fact the function institutions provide in light of the wistful decisions an individual might take. It is an important take-away that bridging the fragility of a development context and the push for innovation in a stable institutional environment can benefit immensely from according these kinds of interpersonal connections a corresponding degree of weight in ascertaining project viability and sustainability.

Methods and mindset of agility

Conditions for hosting the IEIW program were uniquely suitable at the FUB research unit History of the Islamicate World, because a number of enabling factors related to its disciplinary focus. The core of its approach emphatically rejects the unreflected terminology inherent in the application of separate modern-day academic disciplines such as Islamic Studies, Jewish Studies and Christian Oriental Studies onto the past. Such disciplinary divisions perpetuate misconceptions, such as historic spheres of mono-religious dominance and perennial tensions between Islam, Christianity and Judaism that popular discourse often reduces to a shorthand „clash of cultures”. Instead, the subject and its method of inquiry advance a strongly interdisciplinary and intercultural approach so as to develop a terminology beyond the reductive categories of modern-day states, nationalities and religious spheres being super-imposed on historic settings. Instead, the notion of an islamicate world outlines a specific kind of foray into historic research that examines a flow of ideas bound up within the intellectual dialogue among world religions and peoples of pre-modern times.

First Colloquium, first cohort, picture: IEIW

This conceptual dimension makes the idea of a graduate studies program unusually relevant for a practical contribution to the development discourse in the Middle East. It promised to unpack and look beyond the seemingly fixed categories of states, nations, peoples and religious identity, which are regularly projected into history and utilized by all parties, mostly to entrench political conflict and civil strife. In terms of impact, a state-of-the-art academic pedigree would ensure increased visibility of its findings, making them available for a contemporary political discourse of co-operation and peaceful neighborliness rooted in historic precedent. Training young researchers in this field would comprise explicit learning goals in subject matter and research methods, as in any advanced degree, plus explicitly embrace the skills of intercultural communication. The intercultural make-up of the student body in turn would serve as a practical arena for acquiring diversity competence. Program alumni would obtain a premium academic education in the field of medieval studies and graduate with qualifications that would benefit a professional advancement, which they could not otherwise achieve due to lack of access to similar academic programs in the region. More specifically, problems of access in the Middle East included restrictions of movement and travel for Palestinian students especially even to those institutions of higher education locally available to them.

Core conditions for students to meet the intercultural learning goals at least at a minimum threshold is thus embedded into the program’s learning design at the levels of curriculum, teaching formats and learning mode. But tight integration of these general intercultural skills into instructional formats and curricular activities must address a potential snag. Once conceptualized and integrated among the program’s explicit learning goals, the real possibility automatically arises that a given student may fail to achieve them. Just as she may fail to master a particular disciplinary learning goal regarding the subject matter for lack of motivation, effort or ability, she may likewise struggle to develop a set of intercultural communication competencies. This aspect matters, because they are not optional learning outcomes or useful side-effects, but a required element for successful program completion. Moreover, the one-year program duration prevents a student from repeating any given module or to re-take a course in the following semester if course requirements remain unmet. Failing to develop intercultural skills implies failure to complete the program at all.

These considerations highlight the crucial role that scaffolding, mentoring and tutoring students play throughout the program. More fundamentally, they point to the inherent conflict of objectives on the agendas of higher education and development co-operations. To maintain the academic quality that is necessary for achieving the intended development outcomes, no compromise on rigor, performance and assessment standards is permissible in order to achieve a higher student graduation rate. Any such effort would backfire to the detriment of all graduates — past, present and future — as it risks permanent damage to the program’s academic and professional reputation.

The small size of each student cohort meant that every single student who, once enrolled, failed to graduate, incurred not just personal loss and disappointment, but from the perspective of the significant program expenditures incurred for his admission and training, he represents an annual 5% loss of output. Even with a careful selection and admissions process, the overall learning design must therefore take into account the diversity of incoming applicants and be aware of the dependencies between the different kinds of learning goals entailed in the program. Various design decisions and instructional strategies were developed specifically to support and enable students in the successful acquisition of disciplinary and intercultural skills facilitated by blended learning.

When scope and magnitude of a problem cannot be defined exactly up front, conventional project management approaches attempting to crisply define a prioritized list of goals, allocate available resources, identify weaknesses, risks and constraints to then designate key milestones is largely unhelpful in maintaining a big picture perspective. The entire project is too unwieldy, has too many moving parts, too many unknown variables with unclear dependencies on each other that it is best to take a step back and focus on those indicators that are crucial to gauging overall progress.

It is equivalent to a sailor fighting a rainstorm at night while struggling with a leaking boat and a broken rudder but keeping an eye on ground speed. Are we covering distance in the right direction? If the answer is yes, not all the parts of how we achieved this are equally important. It often suffices to focus on the critical ones that keep the vessel afloat and moving forward. Everything else can be dealt with as it comes into view as an actual problem that can and should be fixed. Meanwhile it may be best not to overthink all the different parts of the creaky machinery, as long as they appear to be doing their part.

With such a mindset, it becomes more important to develop suitable solutions based on informed hypotheses, and to rely on short feedback cycles for continuous adaptation of non-standardized workflows. In a notion that is countervailing to bureaucratic dogma, more intelligence and higher degrees of freedom in such cases ought to be attributed to people, rather than processes. Such a combination of methods and mindset creates an agile approach to design and project management that helps to clarify those aspects of the problem that can indeed be addressed effectively. The discovery of suitable solutions, thus conceived, becomes an iterative process of building and testing interlocking elements. The resulting make-shift system delineates a working definition of the problem along with the proposed resolution. If it will always fall short of our aesthetic desire for elegance and simplicity, so be it. What matters instead, is whether it will get the job done as effectively and efficiently as could reasonably be expected under fragile circumstances.

References

- Dentoni, D., & Bitzer, V. (2015). The role(s) of universities in dealing with global wicked problems through multi-stakeholder initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 106, 68–78. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.050

- Epelboin, Y. (2016). MOOCs: A Viable Business Model? In M. Jemni & M. K. Khribi (Eds.), Open Education: from OERs to MOOCs (pp. 241–259). Berlin: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-52925-6_13

- Herbert, U. (2007, August 30). Kontrollierte Verwahrlosung. Die Zeit. Hamburg. Retrieved from zeit.de/2007/36/B-Geisteswissenschaft/komplettansicht

- Seifert, T. Goodman, K., Lindsay, N., Jorgensen, J., Wolniak, G., Pascarella, E. & Blaich, C.F. (2008). The effects of liberal arts experiences on liberal arts outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 49(2), 107–125. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-007-9070-7

- Winter, M. (2013). Studienplatzvergabe und Kapazitätsermittlung – Berechnungs- und Verteilungslogiken sowie föderale Unterschiede im Kontext der Studienstrukturreform. Wissenschaftsrecht, 46(3), 241–273. http://doi.org/10.1628/094802113X13841770055498

- Würtenberger, T., & Fehling, M. (2000). Zur Verfassungswidrigkeit des Curricularnormwertes für das Fach Rechtswissenschaft. JuristenZeitung, 55(4), 173–179.

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top