5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

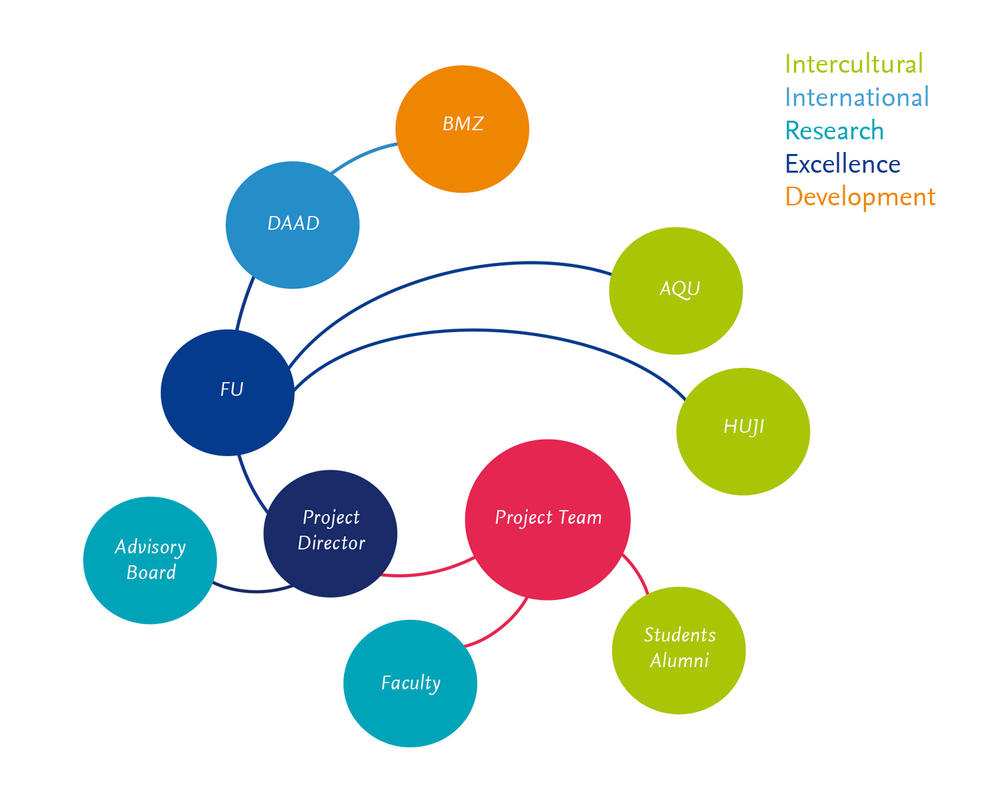

Figure 11. Stakeholder expectations reflect conditions in their respective context.

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

Introduction: Negotiating stakeholders agendas

Reflecting the multi-facetted expectations for the IEIW project was the complex web of interdependent stakeholder relationships within the German higher education and development landscape, which sustained and monitored the IEIW project throughout its lifetime. This organizational framework of stakeholders is highly institutionalized, densely regulated and structurally conservative to the point that systemic innovation - whether it be pedagogic, digital, administrative or otherwise – faces a solid amount of institutional inertia if not outright active resistance. It is, in other words, the opposite of fragile.

A tripartite set of criteria was defined for the Master program long-term impact. It should foster the internationalization of its host university (FUB), it should contribute solutions to regionally specific challenges in the fragile context, specifically the Middle East conflict, and it should align with sustainable development goals in the region. These measurable outcomes should be achieved primarily through the active participation of program graduates in reducing intercultural conflicts and tensions, both in their professional and private lives.

Project funding was provided by the Federal Ministry for Economic Co-operation and Development (BMZ), by way of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) as the administrative and supervisory organization for allocating funds and monitoring progress, with the Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt, AA) providing some informal initial support for the emergent tripartite partnership among the universities involved. These organizations and their respective position in the overall landscape of higher education and development efforts in Germany must be considered as strategic stakeholders in all project outcomes, in light of their different agendas and corresponding indicators for success.

These varied stakeholders on a federal level each pursue overlapping, but ultimately different agendas. The State Department brings a wealth of experience in the region and a long-term perspective on the peace process to the table. An opportunity to support activities in higher education for Palestinians is a welcome corollary to its usual programs, aiding the development of local civil society structures parallel to the usual diplomatic and state channels. The Ministry of Development, with the main focus on regional development, likewise embraces the opportunity to extend its reach into a fragile context such as Palestine. An alignment with higher education initiatives in the region brings a possible addition to its existing programs for professional and vocational training.

As the main federal stakeholder for funding and oversight of international higher education programs, the DAAD is not only the natural partner for distribution of funds and supervision of the project. It is itself keen to explore the potential of digitization and uses of educational technologies to further its mission, increase internationalization, and facilitate student and researcher mobility. Leveraging these technologies would allow DAAD to more effectively reach target audiences in the higher education sphere, which so far remain outside of its necessarily state-bound reach, due to fragile conditions in the target country.

Imagine for a moment the overall IEIW project in its actual, current design as a regular on-site program hosted at FUB or a similar institution. In this on-site version of the MA program, the diverging agendas of underwriters, stakeholders, administrators and participants as described above would still apply more or less unchanged. Taking this premise as a starting point, the development of blended learning solutions for educational programs aimed at teaching not just disciplinary expertise, but general cognitive and meta-cognitive skills, highlights yet again an instrumental view of technology. The focus is now on those pedagogical and instructional practices, that can be identified as a function of the technologically mediated design of the program.

The issues resulting from divergent strategic goals on an operational level require a continued optimization of alignment among stakeholder agendas, priorities and criteria. Like any co-operation, these are relationship commitments that demand compromises from all sides for an optimal outcome. Aside from their operational tasks, the project team had to continuously engage in macro-level organizational relations and stakeholder management with a dual challenge. On the one hand, it meant balancing the expectations emanating from a robust, densely regulated educational landscape in Germany with the fragile contexts of their university partners and students. At the same time, these organizational issues of compliant administrative workflows, notoriously labor-intensive on their own, also had to be communicated sensibly across intercultural boundaries so as to suitably address the respective recipients. This section contrasts the two organizational frameworks and describes the negotiation tactics required to maintain a sufficiently flexible space of administrative action for the project team.

Outcome evaluation and incentive structures

The IEIW project was to establish an internationally visible graduate program of top-tier academic quality („academic excellence”). Alumni were to be qualified for successful professional careers in the field of intercultural dialogue („training”) and participate actively in local and international structures engaging in such dialogue („networks”). Finally, students and instructors participating in the program are maintaining long-term alumni relationships with the hosting university in Berlin („internationalization”).

In accordance with the guidelines of the funding agencies, the project proposal defined for main goals as criteria for impact and success. Initial target audience were outstanding undergraduate degree-holders in medieval theology or related fields in Germany, Israel and the Palestinian territories who are interested in a graduate degree program to further their careers as academic researchers or advanced professionals.

In order to have a practical impact on the post-graduate lives of its alumni, an educational program must provide not only for successful learning outcomes but also validate them with the corresponding legitimacy of symbolic academic capital. Especially in a subject matter such as medieval cultural history, where the skills acquired in the training provided are somewhat intangible and unfold over time, it is crucial to address the symbolic dimension of higher education and provide solid credentials that will be accepted and valued in the students’ local context after completion of the program. A strong emphasis on academic excellence in applicant selection, faculty recruiting and assessment of learning outcomes is therefore a crucial component to program success. Studying intellectual discourses of the medieval era would thus create benefits for both individual participants and the broader region, whether students would pursue academic or non-academic careers after completing their degree.

The additional workload this creates in a third-party funded project concerns transparency and evaluation cycles. There is an existential requirement to evaluate results so as to be able to apply for contingency funding. Once operations are somewhat reliable, resources can be devoted to the strategic task of project continuation. Stakeholders on the German side would need to know that the project aligned with their frameworks of evaluation and impact monitoring. Regular quality assurance reports and a thorough evaluation of project outcomes in accordance with a catalogue of impact indicators captured outcomes and impact according to detailed criteria specified within the original grant.

By all accounts of these results, the project was successful. In terms of achieving the intended learning goals, student surveys and external evaluations proved conclusively that skills for intercultural dialogue and conflict resolution were effectively developed for all participant cohorts. Less clear is the impact of these qualifications on the professional development of program graduates to leadership qualities and executive career positions. Reliably measuring this kind of effectiveness is a familiar problem from leadership trainings more generally, because their application is discernible only in the medium or long term and requires corresponding follow-up studies among alumni.

The performative quality of these administrative workflows and their related practices is crucial to recognize. When dealing with „wicked“ problems, that are not restricted to one field of expertise, one particular location or population, the complexity of environmental variables makes it impossible to gauge impact of emergent practices. To succeed with this approach, the required mindset needs to be attuned to the gradual evolution of the design process and project scope being shaped simultaneously. Project milestones develop through multiple iterations of the program, and are best understood as snapshots that contribute significantly to current understandings of the problem’s shape and the scope. It just so happens, that this mindset resembles nothing so much as the academic approach and the methodological toolkit of science in general and of the humanities in particular, where discursive practices are considered powerful tools in shaping research questions and findings.

The underlying rationale for these activities draws on a particular understanding of educational responsibility embedded in the learning design. Once a student has been accepted into the program, strong incentives exist for all stakeholders that she would complete it successfully. An early dropout or a failure to graduate signifies wasted resources both in terms of project funds and in terms of the student’s material and opportunity costs. Developing a curriculum sensitive to these incentives invariably faces contradictions inherent in the multiple overlapping program goals, though. Following the logic of educational goals, a continuously high graduation rate is taken as an indicator of program success. Increasing graduation rates by lowering the academic quality is obviously undesirable and unacceptable, because it would damage program reputation and attractiveness.

In contrast, the logic of development goals is geared towards providing access and successful training in intercultural skills to the broadest possible audience at the lowest possible cost, to achieve sustainability and self-sufficiency. A highly selective recruitment process as implied by state-of-the-art academic standards contradicts this expectation. Furthermore, from this perspective the absolute number of successful graduates with a Master degree are a much more viable indicator for success than the graduation rate.

From the perspective of project design, the initial decisions on program parameters formalized in the original grant proposal, point to an important quality in the working conditions of managers and administrators in the project team. The goal set imposed by the external stakeholders, which were the conditions of continued funding and in turn of employment for project staff, define the criteria for project success and thus create their own environment of precariousness and insecurity on an operational level. To be clear, this does not by any means amount to equating the fragility of the Middle Eastern context with the comparatively comfortable working conditions with a large German university. Following the principle of requisite variety (Ashby, 1958), it is simply intended to highlight a quality of the project framework that enabled project staff to better address issues emanating from the fragile context they were dealing with.

It would become quite tangible during the project runtime, that a certain degree of uncertainty and informality on the provider side was not only desirable, but amounted to a necessary condition for its continued existence. It was helpful, even necessary for continued compatibility with the fragility of institutions, organizations and individuals in the Middle East and the Muslim hemisphere beyond.

Admissions policy and graduation rates

A fundamental problem in the assessment toolset of higher education is that it is somewhat ill-equipped to properly gauge, in a manner that can be vouchsafed, various degrees of mastery and self-sufficiency in the skill-set of critical thinking, self-discipline, leadership qualities that are lumped together under the term of employability. To a certain degree, their mastery is performative in the sense that instructors, administrators and fellow students are, over time, able to assert in individual participants progress along a continuum of gradually acquiring, honing, practicing and fine-tuning these skills.

This element of training, however, is hardly captured in the credential the student receives upon successful graduation, because leadership skills in the broadest sense of the word (i.e. encompassing training in intercultural dialogue and self-discipline among others) are not graded and transcend individual disciplines. The challenge then, is how to communicate an alumni’s skills in these dimensions to the outside world in a manner that cannot be easily forged by others who have not in fact achieved this kind of mastery.

Recognizing the importance of such skills is no recent discovery, but a distinctly modern problem is the systematic shortcoming of academic credentials in this regard. Traditional mechanisms of restricting higher education access to social elites implied that the completion of an academic degree was itself sufficient proof of an individual’s personal and professional suitability for dealing with and leading others. This approach can be traced back from contemporary systems of higher education, at least to the medieval canon of the seven artes liberales, whose mastery signaled an individual’s status as a free and autonomous citizen.

Modern higher education programs have a much stronger focus on disciplinary subject matter and, broadly speaking, adhere to meritocratic, egalitarian criteria for access. Yet the function of their degrees persist as proxy variables for not merely disciplinary expertise, but performance and action competence, an available repertoire of effective learning strategies and at least the potential for leadership positions.

To accommodate the greater number and variety in graduates, the role of grading has become of increasing importance so as to distinguish between the different qualities and achievements. The second dimension is the hierarchy of degrees, where successful completion of the dissertation or even habilitation is now considered the minimum qualification for certain prestigious positions, when once a Bachelor degree might have sufficed.

Alumni Konference 2017, picture: Wannenmacher

The additional workload this creates in a third-party funded project concerns transparency and evaluation cycles. There is an existential requirement to evaluate results so as to be able to apply for contingency funding. Once operations are somewhat reliable, resources can be devoted to the strategic task of project continuation. Stakeholders on the German side would need to know that the project aligned with their frameworks of evaluation and impact monitoring. Regular quality assurance reports and a thorough evaluation of project outcomes in accordance with a catalogue of impact indicators captured outcomes and impact according to detailed criteria specified within the original grant.

By all accounts of these results, the project was successful. In terms of achieving the intended learning goals, student surveys and external evaluations proved conclusively that skills for intercultural dialogue and conflict resolution were effectively developed for all participant cohorts. Less clear is the impact of these qualifications on the professional development of program graduates to leadership qualities and executive career positions. Reliably measuring this kind of effectiveness is a familiar problem from leadership trainings more generally, because their application is discernible only in the medium or long term and requires corresponding follow-up studies among alumni.

The performative quality of these administrative workflows and their related practices is crucial to recognize. When dealing with „wicked“ problems, that are not restricted to one field of expertise, one particular location or population, the complexity of environmental variables makes it impossible to gauge impact of emergent practices. To succeed with this approach, the required mindset needs to be attuned to the gradual evolution of the design process and project scope being shaped simultaneously. Project milestones develop through multiple iterations of the program, and are best understood as snapshots that contribute significantly to current understandings of the problem’s shape and the scope. It just so happens, that this mindset resembles nothing so much as the academic approach and the methodological toolkit of science in general and of the humanities in particular, where discursive practices are considered powerful tools in shaping research questions and findings.

The underlying rationale for these activities draws on a particular understanding of educational responsibility embedded in the learning design. Once a student has been accepted into the program, strong incentives exist for all stakeholders that she would complete it successfully. An early dropout or a failure to graduate signifies wasted resources both in terms of project funds and in terms of the student’s material and opportunity costs. Developing a curriculum sensitive to these incentives invariably faces contradictions inherent in the multiple overlapping program goals, though. Following the logic of educational goals, a continuously high graduation rate is taken as an indicator of program success. Increasing graduation rates by lowering the academic quality is obviously undesirable and unacceptable, because it would damage program reputation and attractiveness.

In contrast, the logic of development goals is geared towards providing access and successful training in intercultural skills to the broadest possible audience at the lowest possible cost, to achieve sustainability and self-sufficiency. A highly selective recruitment process as implied by state-of-the-art academic standards contradicts this expectation. Furthermore, from this perspective the absolute number of successful graduates with a Master degree are a much more viable indicator for success than the graduation rate.

From the perspective of project design, the initial decisions on program parameters formalized in the original grant proposal, point to an important quality in the working conditions of managers and administrators in the project team. The goal set imposed by the external stakeholders, which were the conditions of continued funding and in turn of employment for project staff, define the criteria for project success and thus create their own environment of precariousness and insecurity on an operational level. To be clear, this does not by any means amount to equating the fragility of the Middle Eastern context with the comparatively comfortable working conditions with a large German university. Following the principle of requisite variety (Ashby, 1958), it is simply intended to highlight a quality of the project framework that enabled project staff to better address issues emanating from the fragile context they were dealing with.

It would become quite tangible during the project runtime, that a certain degree of uncertainty and informality on the provider side was not only desirable, but amounted to a necessary condition for its continued existence. It was helpful, even necessary for continued compatibility with the fragility of institutions, organizations and individuals in the Middle East and the Muslim hemisphere beyond.

Admissions policy and graduation rates

A fundamental problem in the assessment toolset of higher education is that it is somewhat ill-equipped to properly gauge, in a manner that can be vouchsafed, various degrees of mastery and self-sufficiency in the skill-set of critical thinking, self-discipline, leadership qualities that are lumped together under the term of employability. To a certain degree, their mastery is performative in the sense that instructors, administrators and fellow students are, over time, able to assert in individual participants progress along a continuum of gradually acquiring, honing, practicing and fine-tuning these skills.

This element of training, however, is hardly captured in the credential the student receives upon successful graduation, because leadership skills in the broadest sense of the word (i.e. encompassing training in intercultural dialogue and self-discipline among others) are not graded and transcend individual disciplines. The challenge then, is how to communicate an alumni’s skills in these dimensions to the outside world in a manner that cannot be easily forged by others who have not in fact achieved this kind of mastery.

Recognizing the importance of such skills is no recent discovery, but a distinctly modern problem is the systematic shortcoming of academic credentials in this regard. Traditional mechanisms of restricting higher education access to social elites implied that the completion of an academic degree was itself sufficient proof of an individual’s personal and professional suitability for dealing with and leading others. This approach can be traced back from contemporary systems of higher education, at least to the medieval canon of the seven artes liberales, whose mastery signaled an individual’s status as a free and autonomous citizen.

Modern higher education programs have a much stronger focus on disciplinary subject matter and, broadly speaking, adhere to meritocratic, egalitarian criteria for access. Yet the function of their degrees persist as proxy variables for not merely disciplinary expertise, but performance and action competence, an available repertoire of effective learning strategies and at least the potential for leadership positions.

To accommodate the greater number and variety in graduates, the role of grading has become of increasing importance so as to distinguish between the different qualities and achievements. The second dimension is the hierarchy of degrees, where successful completion of the dissertation or even habilitation is now considered the minimum qualification for certain prestigious positions, when once a Bachelor degree might have sufficed.

Graduierung 2017, picture: Wannenmacher

A third dimension available to confer this kind of distinction upon graduates is institutional reputation - of a certain program, a certain department or a certain university of providing „outstanding” higher education. Ironically, the Bologna reforms effectively implied that one ECTS credit point was just as good as any other, creating a fully convertible currency of higher education whose units can be combined no matter whether they were awarded in Madrid, Milano, Maastricht or Munich.

This spirit found its more recent technological embodiment in the corresponding use of the blockchain to record them as incremental learning achievements in an inviolable ledger beyond the reach of counterfeiters. These efforts overlook a development that stands in stark contrast to the modularization of individual learning units, namely the concomitant stratification and differentiation of the university landscape. Neither grades achieved nor subject matter studied have as much predictive value for future career trajectories as the credentials imbued by the reputation of a certain university. Witness the spread of rankings, the growth of investments into higher education marketing and brand-building, the ever more prevalent language of competition, positioning and profile as well as increasingly selective admissions procedures.

Even before contemporary activities of higher education marketing it is a common and widely accepted approach for institutions of higher education to carefully select those students they admit to their programs. A number of social demographic criteria may play a role in putting together the desired student body, but one would hardly criticize universities for selecting especially those students that have shown the general aptitude, motivation or skill set predisposing them to the learning journey in which they are about to embark. Selection for these kinds of quality does not qualify as selection bias, but as part of regular admissions procedures.

It is understood that admissions criteria limits access to higher education, because a certain substance of prerequisite knowledge is a necessary condition for successful completion of the program. For the IEIW master, the imperative of academic excellence meant that the admissions process had to be quite stringent and to include for example a working knowledge of Arabic, due to the methodological requirements of study. These requirements created a rather narrow corridor for participation and made recruitment in an already niche community quite a challenge.

Neither of these conditions could be lowered, however, as they were not only an integral part of the program’s design, but also preconditions for the stated goal of international visibility based on academic rigor. Viewed from the organizational perspective of the partner universities, however, these formal standards of scholarly excellence could – in a competitive higher education landscape – easily be perceived as a strategy to poach promising undergraduate students from the region via academic brain drain.

An entirely different logic applies to the political dimension of the project, where the overriding goal is enabling access to as broad a constituency as possible, not necessarily distributed based on merit, but based on need and marginalization. Where educational programs have an admissions process, political projects have an entirely different set of selection criteria for the audience of intended benefactors. Within the political and development logic, the criteria for success are therefore quite differently understood, because in political terms a viable foray into fragile contexts amounts to providing a protected space for intercultural sensitization and the practice of dialogue across entrenched identities.

Agile management in peripheral positions

The IEIW project is an example for the use of agile practices of entrepreneurial organizing at the periphery of a robust, institutionalized system such as German higher education. The disciplinary specificities of its subject matter illustrate the innovative potential of technology-enhanced learning in an academic context. Marginal as the topic of medieval religious history may seem at first glance, the implementation of the IEIW program represents more than a mere virtualization of existing analogue pedagogic practices and a move towards methods and concepts of natively digital humanities.

Co-operative ventures with such a degree of complexity can yield valuable insight for the development of future initiatives with a holistic approach to the role of higher education in foreign policy and development interventions. They are experimental in character and their success is by no means self-evident: They explicitly endeavor to depart from the „silo“ approach embedded in the administrative principles of public organizations. To be truly innovative, it is imperative that they actively disengage from established structures and circumvent conventional practices. Nevertheless, they must adhere to the compliance regulations and are subject to institutionalized norms and political proclivities beyond their control. They are required to plan their activities and develop their offerings under conditions of high uncertainty, which implies a high level of agility. The entrepreneurial mindset expected of them places them squarely at the periphery of their respective organizational environments.

The project’s peripheral position allowed stakeholders and participants to identify boundaries they had previously taken for granted as constructed and malleable. Once they discovered their contingent nature, they became able to move, cross and even ignore these boundaries where necessary. An important aspect is the continued feeding of these learnings back into the processes of negotiating and transcending such boundaries. Regarding the activities and structures of the overall pilot project, the contestation and re-negotiation of three particular boundaries have shaped its character as truly innovative and distinct from conventional academic instruction as well as established organizational structures for programs of higher education. History and scope of the project illuminate both their contingent nature and how their taken-for-granted character shapes our expectations, actions and scope of action regarding the use of technology to improve higher education.

Three kinds of taken-for-granted assumptions embedded in the organizations and institutions of higher education create boundaries that challenge designers, developers, instructors, managers and students of innovative learning formats and they will be addressed in turn. The first set of assumptions concern homogeneity, essentially stating that an effective learning format requires an adequately homogenous group of learners. The second set of assumptions concern subject matter expertise, which implies a suitable balance between guided and self-directed learning for adult learners in an academic context. Third and most easily overlooked are the institutional assumptions that attribute unilateral, rational agency to modern organizations such as universities and other bureaucratic entities and leave little room for the entrepreneurial action on an individual level. The institute of Islamic Studies at FUB and its corresponding scientific community follow the logic of previous activities, where the construction of a new field of research posits the format of a Master program as the next logical step for generating focus and possibly train junior researchers. The university and its Department of History and Cultural Studies, on the other hand, see an opportunity for internationalization and a testbed for the development of learning technologies as a boon to its reputation, its activities in this area and an opportunity to gain outside funding for possible strategic growth.

In spite of numerous efforts for institutionalization, the project continued to develop and prosper very much on the periphery of the involved universities. In spite of adhering to the standards of academic rigor, the program gained little strategic importance at its host university FUB, in-house visibility being limited due to its small size and its niche research topic. While noticeable interest for the blended learning formats developed during the IEIW Master, a strategic shift in the overall university’s e-learning strategy both concerning infrastructure and governance made it difficult to transfer and apply project learnings into the broader IT landscape.

Tensions inscribed in the trilateral partnership directly impacted the operational level of program design. The given challenge to create, from scratch and without a template, effective organizational structures and practices must somehow bridge the gap between these different degrees of institutionalization and mediate between them. To effectively manage and complete its assigned tasks, during standard operations as well as in reaction to unforeseen circumstances, its internal setup must possess at minimum the requisite variety of the system it is charged with regulating.

Practically speaking, the decisions and workflows of instructional designers and program administrators in Berlin, geared towards benefactors to access and participate in the program, had to adjust continually to the realities that fragile contexts impose on partner organizations and program participants. These challenges defy a top-down management approach and formalized planning, requiring instead short iterative loops of hypothesis-driven development and continuous feedback-driven improvements.12 Agility in attitude and methods is the suitable principle guiding the venture as a collective design process and forms a decisive quality for its accomplishments.

The overarching theme connecting the two designs contained within the IEIW program is the iterative motion of agile design and development that every educational practitioner is familiar with. Quality assurance and development in higher education especially is achieved by continually adjusting and optimizing a given set of design choices rooted in experience and theory, based on empirical outcomes and feedback through multiple instances of an instructional format. Learnings related to the experimental nature of the project, which was officially launched as a pilot, concern not the static and quantifiable results of individual learning outcomes for participating students. They focus instead on the accumulated learnings for managing and developing a technology-enhanced course format and its administrative support structure. Front and center of these findings are the multitude of decisions, negotiations and experiments that eventually fused into the actual shape of the program. Understanding the dynamic of these design processes and the form of the associated practices benefits future ventures of a similar kind.

Notes

12. The notion of agility originated as a design principle for software development (cf. http://agilemanifesto.org/principles.html), to better deal with complex uncertainties. It refers to an iterative approach with rapid, result-oriented prototyping, driven by close feedback loops with the customer. The concept has recently spread to various areas of design, innovation and management, including higher education (Gautschi & Schmid, 2018).

References

- Ashby, W.R. (1958). Requisite variety and its implications for the control of complex systems. Cybernetica, 1(2), 83–99. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0718-9_28

- Gautschi, P., & Schmid, F. (2018). Mit mehr Agilität die Hochschule gestalten. Zürich: Berinfor.

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top