4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

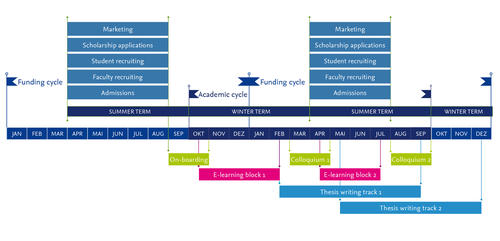

Figure 9. Ramp-up for the program pilot rests on hypotheses to be ve

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

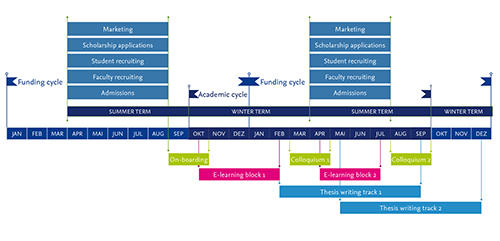

Figure 10. Steady-state operations of the program yield data points for adaptation.

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

Introduction: Administrating complexity

Up to 20 Israeli, Palestinian and German students enrolled in the Master program „Intellectual Encounters of the Islamicate World“ at the Department of History and Cultural Studies at Freie Universität Berlin (FUB) each fall from September 2013 onward. They had applied and were selected to study the history of thought in the islamicate world from the medieval era to early modern times for the duration of two semesters according to the standard academic calendar.

Their specific focus on the scholarly exchanges and collaborations between representatives of Christianity, Judaism and Islam required previous undergraduate training in a related field. English was the language of instruction as teaching and guidance were provided by a renowned international faculty. Students examined the interwoven intellectual roots of these monotheist religions in the areas of theology and exegesis, philosophy and logic, law, mystical traditions and the history of science during a 12-months course of study.

In contrast to most theological or historic-philological research of this subject, the program is premised on an interreligious perspective and transdisciplinary methods. It is grounded in an emergent field of research, aiming to unearth the profound connections between three world religions at a time when their familiar modern characteristics were much less firm. A key objective of the field is to supply historic foundations for contemporary religious tolerance and dialogue, by making commonalities in religious tradition visible and improving mutual understanding.

The Master program emphasizes rigorous academic standards and training in hands-on research, requiring working knowledge of Arabic for the examination of historic sources. The student body is chosen for its cultural and religious diversity so as to reinforce the importance of an interreligious perspective effectively and encourage multiple viewpoints on the subject matter. Students can therefore develop and train capabilities in intercultural dialogue both in research of the subject matter and in collaboration with their fellow students. The program aims to create a protected space for students to undertake unfamiliar intercultural encounters, far removed from the tensions of contemporary political conflict.

The program is offered as distance-learning in a blended learning format to encourage applicants from a broad range of backgrounds. Around 80% of instruction over the course of two semesters take place via synchronous online seminars using Adobe Connect™. Asynchronous learning is possible via a digital classroom that was implemented in a project-administered instance of the popular Moodle™ LMS until the summer of 2018 and has since then been migrated to the Blackboard™ LMS as part of the university’s overall IT strategy.

Three on-site colloquia frame the e-learning phases. Students and instructors meet for a two-week research colloquium in Berlin at the program mid-point in February and at the conclusion of the teaching phase in August, before students begin writing their theses. A one-week workshop for on-boarding the incoming students is conducted in September, in a location symbolic for interreligious exchange. Most recently this orientation week was held in Córdoba, Spain; previous events took place in Istanbul, Turkey, until security reasons made the location untenable.

The IEIW Master was a pilot project for improved higher education access in politically and economically fragile contexts, based on a unique stakeholder co-operation to experiment with digital learning technologies. The IEIW program charges students no tuition fees whatsoever, travel expenses for the on-site events are covered for students from Israel and Palestine. In addition, Palestinian students especially may also apply for a scholarship to cover living expenses for the duration of the program. Project sponsor and supervisor was the non-profit agency charged with international academic exchange and co-operation, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD e.V.). It is remarkable that this decidedly academic program formed the heart of a project for regional economic development, made possible by funding awarded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Co-operation and Development (BMZ) from 2013 to 2019. From a development perspective, the four successive project grants contribute to efforts in the Middle East peace process with its focus on intercultural dialogue as a learning goal for its alumni. Economic development in the region is supported by broadening access to state-of-the-art graduate studies for future professionals.

Although six paragraphs are required to describe the program concisely, in hindsight its features exhibit a remarkable degree of organic coherence. The snug fit between strategic goals and operational practices risks obscuring the underlying administrative complexity. This section therefore offers a forward perspective from program inception on. It outlines the processes necessary to launch the program pilot successfully and to operate subsequent steady-state iterations from a project manager perspective. To operationalize funder intentions, shape and structure of the project design became intensely familiar with the consequences of exposure to a fragile context. A key aspect of hosting the program at FUB was this ability to engage with “double-loop” learning (Argyris, 1991) to maintain the balance of strategic continuity and iterative change.

Minimum viable pilot to validate assumptions

The trade-off between the political goal of access to intercultural training and the academic goal of excellence is palpable in the challenges for marketing the program and recruiting applicants. In terms of regional development, practical parameters regarding benefactors were to consider. The program required students to possess a working knowledge of Arabic, but the working language for teaching and learning is English. A set of skills related to academic background and research training in a prior undergraduate program are necessary and must be complemented by a high motivation for self-regulated study and the willingness to engage in intercultural exchange. This set the bar for applicants quite high.

In spite of its excellent academic reputation and intensive marketing efforts, including an annual trip to the region with on-campus events in the relevant departments, the number of suitable applicants in the early iterations of the project remained lower than anticipated. Among the most efficient tools for successful recruiting were personal recommendations of instructors, current students and program alumni on the one hand and digital communications via web sites, social media and similar channels. This points to the fact that actual demand existed, but that understanding the features of the project continued to pose a significant hurdle in the marketing process.

An expected challenge to be addressed within the program, due to the diversity inherent in program parameters, were intercultural frictions on the participant side once students had enrolled. But the fragile context of the Middle East exacerbated some of these discrepancies into veritable obstacles already during the marketing and recruitment process, both for individual students and organizational stakeholders. Should the course website be made in English only, for example, since fluent English is required for course participation? Or would an Arabic version add credibility and clarity to the program’s intended audience? But this would necessitate a version in Hebrew and in German as well, to demonstrate the balanced approach of the program. Questions such as these become relevant in light of limited available resources and in-house skills for maintaining multi-language communications over time. They also entail the risk of raising the wrong kind of visibility among competitors or outright opponents of such intercultural efforts. Thus in spite of the multitude of digital marketing channels available, the need for targeted and sometimes discreet communication within fragile contexts were strong arguments for continued reliance on personal connections and conventional printed matter such as flyers and brochures to reach the potential target audience in Palestine especially.

Erstes Kolloquium erster Jahrgang, Picture: IEIW

As in any higher education intervention, the pilot run was supposed to test some basic assumptions and to provide a proof-of-concept for continued operation. Nevertheless, some pragmatic trade-offs have to be made in light of the multiple considerations in play. For the testing of the key hypotheses, in other words, not all parameters of the pilot have to be fully formed. It is more effective to apply the design perspective of a minimum viable product (MVP) to the pilot and with only the barest of required expenditures test for the one hypothesis that will help determine strategic viability of the entire project (Moogk, 2012; J. Münch et al., 2013).

In the case of the IEIW master, it was plain to see that this key feature would have to be related to the achievement of intercultural learning goals. Could the mechanisms of the East-Western Divan Orchestra of joint focus on a demanding activity to overcome politico-cultural fault lines be replicated in a graduate academic program? Could a sufficient number of suitable applicants with the requisite disciplinary and social skills be identified and successfully shepherded through a one-year program of online learning with verifiable improvements in their intercultural competencies? It is easily forgotten in retrospect, that the answer to these questions were everything but self-evident in 2013. Moreover, if the pilot could not provide a positive answer to them, all other efforts of the team regarding technological innovation, supremely qualified faculty and employability of graduates could not save the program from a fundamental miscalculation.

Testing this key assumption behind the learning design in a minimum viable pilot was thus existential for any further investments in the project design. With the MVP approach came an inevitable corollary, however, that is likely apparent to anyone familiar with the launch of an educational program, namely a one-time trade-off in academic quality. If decisions have to be made about what constitutes minimum viability, resources must obviously be held back in some other areas of the pilot that may be added later. Thus, while scientific standards of excellence were an indispensable strategic property of the IEIW project, they are impossible to manufacture and predict ex ante.

Faculty and curriculum can facilitate their emergence even during a pilot iteration, but the incoming student body in all their glorious diversity represent an unknown quantity of significant impact. What kinds of knowledge will they bring, what deficits will have to be compensated for? What kind of motivational or didactic issues will have to be addressed? What administrative problems will emerge if such a variegated student body is enrolled at FUB simultaneously? These questions will determine the internal qualities of the learning design and they are impossible to answer until the pilot is underway. Nevertheless, if the desired academic standards - in student papers, for example - are not achieved on the initial pilot run of the program with the help of serendipitous circumstances, the downside is minimal. As long as the MVP hypotheses regarding the intercultural learning can be validated, it will be much easier to hone quality standards over time in future iterations, more so because future applicants will have a reference case on which they are able to gauge their expectations and suitability for the program.

Student marketing, recruiting and commitment

For students to successfully apply, enroll and complete the program, their expectations, incentives and handicaps as determined by the fragile local conditions were to be identified and addressed with a high degree of adaptability. On the provider side in Germany, however, a densely regulated environment and a highly institutionalized system of higher education limits the available innovation space. The program therefore needed an administrative support system, whose procedures could buffer conflicting demands initially, to optimize them iteratively over the duration of the entire program.

Applying to a graduate program of study is a life choice with significant opportunity costs, so for potential students it amounts to a multi-stage process of decision-making commonly modeled as phases of attention, interest, desire, action (AIDA).11 During each phase of this process, applicants make a selection between several alternatives and must be presented with a corresponding value proposition that helps them narrow down their preferences and make a decision. In the evolving marketing strategy of the project, targeted efforts were made to address each phase with corresponding measures. Questions of strategic communications beyond the immediate marketing and recruiting needs for the IEIW program played a crucial role in effectively proving existing learner demand, both during the pilot phase and the later iterations.

Innovators everywhere face similar challenges. Precisely because they offer something new, different and unconventional, it is difficult to frame its relevance and value in the established categories of an established field. In the case of the IEIW, the actual complexity of the project involving stakeholder co-operations, the multiple learning and development goals, an interdisciplinary research perspective, the specially designed blended learning curriculum etc. were all necessary ingredients into the successful launch of the program. For the intended audience, however, these same features made it difficult to understand the value and the format of the program. For recruiting the pilot cohort of students this was especially challenging, because applicants would have to base their trust into a program with no prior reference points.

Generally speaking, a lack of program reputation can be compensated to a certain degree by the institutional reputation of the host university. But it was clear to the founders in this case, that especially the recruitment of Palestinian students would have to rely on personal networks and word-of-mouth, not just in the pilot year but probably during subsequent iterations as well. The features contributing to the fragility of their livelihoods would necessarily impede both the overall demand for such a program and the individual value proposition associated with such a commitment that carried immense opportunity costs but little in terms of immediate pay-off.

Assuming that academic supervisors and faculty have created a suitable learning design, a host of issues remain in dealing with the administrative tasks involved in the successful launch and continued operation of the initial cycle, all of which are characterized by a high degree of fundamental uncertainty. As in any innovative endeavor, there are some glitches to be expected and some wrinkles to iron out. These become more difficult to recognize and to address in an interdisciplinary online setting, where feedback is mediated and often time-delayed on the one hand, and frames of reference differ due to multiple disciplinary backgrounds. Project management is made more challenging still, when the intercultural dimension of translation and decoding becomes involved.

The diversity that is necessary and desirable in the IEIW learning design manifested itself on the level of administrative workflows, where standardization and routines are the expected norm, especially where they interface with the university environment of FUB or the institutional expectations of external funders. Finally, the fact that fragile contexts are involved raises the stakes substantially and reduces especially administrative margins of error. Student tolerance for delays and faults in solving administrative questions is significantly lowered than in conventional programs, as such questions can immediately impact their financial and legal base for program participation.

The short cycle of the program requires substantial and reliable commitments from administrators, instructors and students up-front. After the highly selective application process is complete, all three groups therefore share strong incentives to maximize their utility. If a student is admitted, but does not complete the program, real cost is incurred on all sides - no matter whether the cause was an early drop-out (which was successfully avoided throughout the project duration) or failure to complete all graduation requirements (which was successfully avoided in all but a few exceptional situations). These scenarios pose a real threat, not only because resources and opportunity costs have been wasted. Because of the important role diversity plays for the student cohort in each program iteration, losing even one student would have a direct side-effect of diminishing the carefully balanced intercultural learning context for the remaining student cohort. The project team is therefore responsible for collecting the accumulated experiences during each academic program cycle and use them as the building blocks for strategically viable routines in subsequent cycles where possible.

Inherent in both the strategic and the operational perspective is a strong orientation toward the specific demand of benefactors, namely the student audience whose expectations are shaped by fragile contexts as well as demands for compatible outcomes embedded in the institutional framework on each side of the intercultural co-operation. The resulting tasks for the project team necessarily expanded far beyond the usual scope of learning support and program administration. Its function as the main channel to services and collective knowledge of the host university, meant that it was perceived by both students and faculty as the interface for a host of issues (such as digital literacies, career advice, psychological counseling, financial services, legal advice, health services, travel management) that are normally provided by specialized university departments. As part of their commitment, project staff was therefore obliged to acquire necessary expertise beyond their original skill-set and assume a variety of unfamiliar roles to effectively interact with program participants on the one hand and the surrounding organizational environment on the other.

Flexibility for continuous adjustment

Figure 10. Steady-state operations of the program yield data points for adaptation.

During the creation, launch and repeated iterations of a new educational format a significant shift in focus occurs. The pilot iteration of the program also creates performative points of reference, however, where previously there was only an empty space of projection and intuition. The initial investment to launch and operate a successful pilot amortizes over several years. Structures established on the basis of an informed guess may be stabilized, make-shift become routines to be optimized on the basis of actual experience.

An example is the timing of thesis-writing and program graduation. It was originally envisioned that students would write their thesis during the summer term, parallel to the second set of modules. This proved too challenging for the majority of participants in terms of workload. For the cohorts from the second iteration forward, a two-track system was introduced that would permit students to complete their thesis within three months following the completion of the course phase. Of course, this created a new problem concerning the graduation ceremony taking place at the end of the third on-site colloquium. Allowing students to extend the thesis-writing period after the second semester ended meant that they would not have in fact completed the degree requirement on the scheduled day of the ceremony and no diploma could be handed to them.

The compromise solution was pragmatic and Salomonic at the same time: The ceremony itself, as anyone who attended it can confirm, is an intensely emotional event that celebrates the cohesiveness in diversity students have acquired over the course of the year. It pertains, in other words, to the intercultural learnings as much if not more than to the formal aspect of credit points and graduation certificate. With an emphasis on the ceremonial aspect, the soon-to-be-alumni have the opportunity to celebrate their individual and shared achievements while enjoying each other’s immediate presence. It is only afterwards, that many of them embark on the more lonely task of writing their thesis to hand it in for the proper Master credentials issued by the university.

Furthermore, a number of assumptions regarding student relations could be corrected with the learnings from the initial pilot cohort. During the first year, Palestinian students were provided with their own laptops, on the assumption that they would not otherwise be able to access the online classroom and participate in digital interaction. This perceived inequality between participants created palpable dissatisfaction within the student cohort. The pilot iteration revealed that nearly all Palestinian participants were equipped with suitable devices of their own, so that the practice could be adapted. Lack of technical infrastructure on the students’ side, it turned out, was a minor problem at most. Indeed, some of the docents brought hardware to the program that was older and occasionally more problematic to use for online classes than the hardware the students themselves owned. A crucial resource throught the program, however, was technical support for the setup and configuration of laptops for students and faculty alike. The project’s IT administrator regularly spent a significant amount of time supporting various hardware models and operating systems with software installation and troubleshooting far above and beyond the regular service levels a university’s central IT department is generally able to offer its students. Here again, it turned out that on-site availability of know-how and capacities for immediate support contributed much more significantly to smooth operation of online classes than any investment into hardware or software infrastructure.

Erste Einführungswoche erste Gruppe, Picture: IEIW

A similarly unequal distribution of program resources had to do with travel expenses for on-site events. Based on academic qualities, topical focus and intercultural exchange, program participation did offer an attractive proposition for potential students of medieval history who actually resided in Germany. The online elements of the curriculum meant that not only local students living in Berlin, but indeed students from all of Germany could participate. Due to funding being made available with a designation for development purposes abroad, however, it was formally impossible to offer an attractive value proposition for university students of the subject within Germany, unless they happened to reside in or near Berlin. The project proposal had emphasized from the very beginnings the important role that the participation of German students would play in the project, both as mediators in intercultural dialogue and as future researchers for a notoriously underrepresented field. Nevertheless, it proved difficult to recruit students for the IEIW program, because of a completely different incentive structure in the „stable context“ of German higher education, where the potential target audience has numerous choices for university study without tuition and tend to prefer on-site learning to an online program. Because IEIW program funds originated in the Ministry for Economic Co-operation and Development (BMZ), they were earmarked for exclusive disbursal to foreign citizens. As a result, German students as a rule could not be compensated for travel expenses to the on-site events in Berlin, Istanbul and Còrdoba.

Such expenditures might appear as reasonable investments in the context of substantial tuition fees, the expectations (and budgets) of German Master students, immersed in an educational system where no such tuition fees exist, perceive such spendings as an extravagance. As an informal and largely unanticipated solution, Israeli and Palestinian students regularly invited the accompanying international students to share their hotel rooms with them. Hotel staff was made aware in advance of such arrangements and proved willing to accommodate all such situations without hassle. While this anecdote makes for an inspiring example of pragmatic intercultural solidarity which in project terminology at any rate contributes to desirable learning outcomes, it should be noted that such a solution would have been impossible to propose by the project’s administrative staff nor could it have been condoned by the compliance department of funding agencies. Less mundane matters were on the minds of program initiators, when they referred in the original IEIW project proposal to „emergent progress in mutual respect by approximation“ of students.

A related point regarding the absence of tuition fees further impacts the ability to recruit students from Germany to participate in the program. In the „stable context“ of the German higher education, the added value of a high-end graduate degree without no associated tuition costs is difficult to perceive as such for most domestic students, since undergraduate and graduate education in the public university system does not generally require such tuition to be paid. A much more salient point to these students is therefore the high degree of specialization and the Arabic-language skills requirements, that tend to amplify difficulties in recruiting from the German landscape.

Notes

11. The DAAD has published a compilation of good practice higher education marketing projects that broadly follow the AIDA model (Eggers, Klaus, Münch, & Stuckenholz, 2016).

References

- Argyris, C. (1991). Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review, 4(2), 4-15.

- Eggers, L., Klaus, C., Münch, C., & Stuckenholz, F. (2016). Weltweit und virtuell: Praxisbeispiele aus dem digitalen Hochschulmarketing. (DAAD, Schriftenreihe Hochschulmarketing). Bonn: GATE-Germany. http://doi.org/10.3278/6004519w

- Moogk, D.R. (2012). Minimum Viable Product and the Importance of Experimentation in Technology Startups. Technology Innovation Management Review, 2(3), 23–26. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/535

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top