2. Shaping a higher education intervention

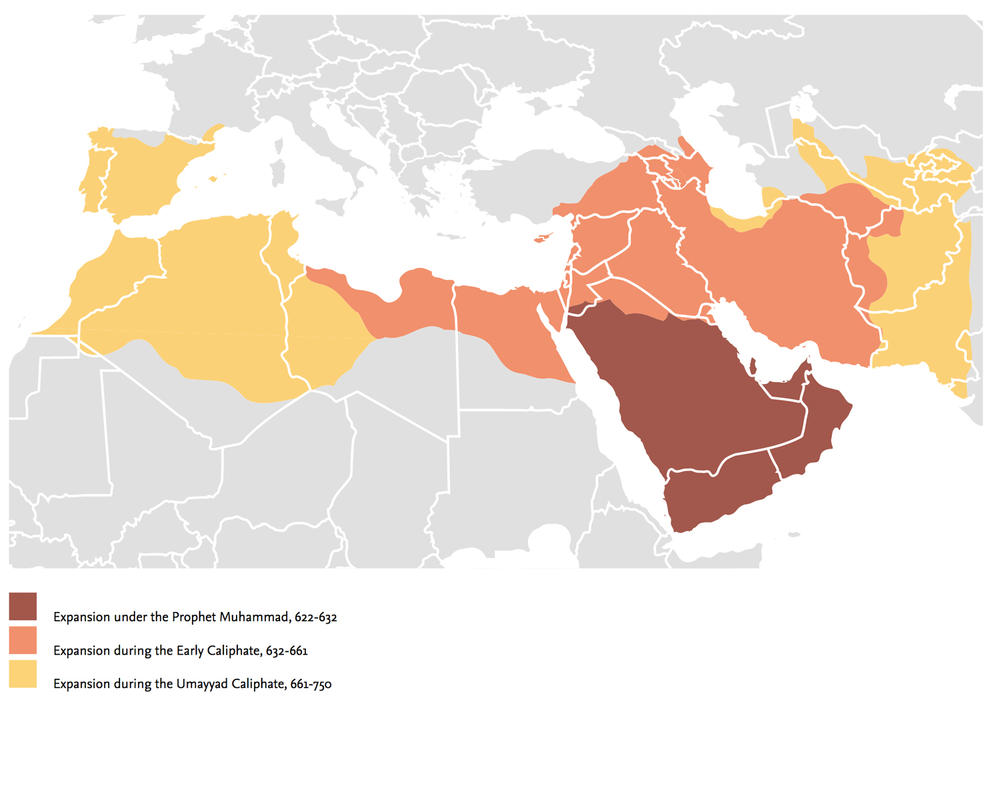

Figure 7. The cultural space of the medieval Islamicate world transcends familiar modern state borders and regional contiguities.

Image Credit: Public Domain

Introduction: A mindset of design

What is or ought to become digital in the “digital humanities” often remains underspecified. The term’s references and actual uses can be fraught with connotations that are neither conceptually nor methodologically demarcated clearly (Raunig & Höfler, 2018). Current discussions center on the use of digital tools for research, such as making materials digitally available, or making natively digital materials accessible to philological and historical methods (vgl. Vogeler, 2018). These efforts rest on the rather timidly stated conviction that the humanities have something vital to contribute to the understanding and analysis of the post-digital society, which is rooted in a core methodology of interpreting and reflecting on texts and meanings (Krämer, 2018).

While such activities are a central concern of current research programs, however, it remains unclear how digital technologies can meaningfully contribute to learning processes and instructional formats in an academic context, where an initial reaction to technology-enhanced formats (especially in German-speaking contexts) is one of skepticism due to the loss of social presence implied in a mediated, asynchronous teaching-learning arrangement. This blind spot is attributable in part to the rapid technological innovation cycles that are largely driven by software engineers and commercial markets, not educational designers and institutions of higher learning8. The technical expertise and practical skills required for experimentation with new technologies in academic teaching continues to be rather high, while there is little to no career incentive for most junior academics to move beyond a mere instrumental use of digital tools, leaving the rest up to strategic decisions in their local e-learning departments.

A notable distinction of the IEIW project in this regard is not that it possessed an initial expertise or even propensity for digital learning. Instead, it was the organizational hypothesis that a small, scattered field could benefit from a joint virtual space for teaching and learning that from the outset relegated the technological aspects to a means, rather than an end in themselves. This impulse can be called entrepreneurial, in line with recent observations that “itinerant academics” (Whitchurch, 2018) have to constantly adapt to different, unfamiliar roles in an environment of precarious funding and nonlinear career paths. Yet it is notable that seasoned researchers and scholars, undeterred by the layered complexities of their vision, ventured forth with a great deal of enthusiasm and an uncharacteristically narrow basis of empirical data to support the hypothesis entailed in their project.

Of course, the higher education and development goals of the IEIW project were grounded in professional experience and scientific theory. Yet the creation of a real-life program for imparting knowledge and skills to students had to rely on a toolkit that differed substantially from methods that researchers have traditionally relied on for generating knowledge. What educators and e-learning developers create is expected to make the world a better place, whether it be material artifacts or social activities. In their highest aspirations, they succeed in creating efficient, effective and elegant systems of teaching and learning. In tackling these tasks, they embrace the mindset and the methods of designers. The strategic insights that may be gleaned from the iterations of the IEIW program thus concern design challenges and corresponding solutions.

Experienced users of digital learning technologies realize, of course, that the numerous apparent benefits of such virtual educational settings accrue only if they are supported by investments elsewhere. A well-established research finding after a century of technology-enhanced distance learning holds that learning outcomes are independent of a particular medium, whether it be correspondence courses, radio, television, CD-ROM, the World Wide Web, mobile Apps, MOOCs or other emergent forms of e-Learning (R. C. Clark & Mayer, 2016). Instead, the key determinant for successful individual learning outcomes is the suitability of the instructional design choices (Merrill, 2012). The pedagogic and instructional challenges largely determine the effectiveness and efficiency of such designs and have been thoroughly researched and documented elsewhere (Araya, 2013; Davies, 2011; Gross & Davies, 2015; Mcloughlin, 2016; OECD, 2013; cf. 2015). The scope of this study does not permit either a thorough critical review of this body of literature nor does it claim an actual contribution to this field of research. Suffice to say that the conception, production and operational administration of a suitable instructional design is a labor-intensive, costly and complicated task, whose strategic milestones are outlined in this section.

Designing learning for complex general skills

The challenges involving the creation of a successful learning design from scratch are considered here as generalized principles. They manifest themselves in concrete design decisions and operational tasks ranging from faculty and student relations to administrative workflows and strategic program management. Relying on technology-enhanced instruction and blended learning at a distance by itself neither helps nor hinders skills-training for intercultural dialogue with participants from fragile contexts. As long as the instructional design itself is suited to the intended learning goals and provides learners with adequate scaffolding, feedback and assessment, there is no inherent reason it should fail.

Having said this, combining acquisition and practice in general cognitive skills, such as intercultural dialogue, with transdisciplinary graduate studies in a specialized subfield of the humanities is a complex instructional design challenge. The knowledge associated with awarding a graduate academic degree is conventionally related to specialized disciplinary skills. The first hypothesis to be tested by the learning design of the pilot program thus concerned the acquisition of intercultural skills by students during the study of historic sources, which involved empirical evidence of fruitful intellectual exchange between representatives of different religious cultures. Engaging them in academic analysis of such commonalities could create a rational foundation for questioning deeply seated assumptions. Hermeneutic reflection on identity and otherness in the program’s subject matter could be expected to broaden geographically and deepen intellectually a given student’s initial worldview. Graduates would thus acquire a more inclusive perspective regarding the roots of modern-day politico-cultural conflicts in the region and the diverging viewpoints on a given interlocutor.

During their program of study, students were to familiarize themselves with the history of ideas in the medieval Islamicate world and examine the intellectual roots of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The program curriculum could thus be construed as a mechanism for enhancing the participants’ intercultural understanding while they simultaneously developed skills for intercultural dialogue. These same skills for intercultural competence would be deepened by academic reflection and research practice related to the program’s subject matter. A second hypothesis to be tested by the pilot therefore involved the students’ shared commitment to the demanding activity and discursive engagement with a diverse group of fellow students that is a basic method of the humanities. Contrasting the conflictual situations in the contemporary life-world of participants from the region, the program could create a concentrated learning community. It could allow students to engage with a challenging topic of shared interest in a neutral space, albeit virtual, where they were removed geographically and temporally from present day lines of conflict.

Explicit emphasis in both skill dimensions rests on imparting knowledge to and building the skills of intercultural dialogue of program participants. Studying the commonalities of medieval religious discourses firmly embedded an intercultural perspective in the methodology of the subject matter, enhancing disciplinary knowledge. Collaboration within a culturally and religiously diverse student cohort ensured the integration of the practical exercise of such dialogue in the immediate learning environment, increasing corresponding cognitive and metacognitive skills. To alleviate the inherent tension between them, the program design had to successfully balance these two kinds of knowledge and accept the inevitable trade-offs between them.

An enticing feature of this learning design is the positive feedback-loop of mutual benefits entailed within it. Active participation of Palestinian students in a state-of-the-art graduate program of study that offers an internationally recognized degree from a renowned university would obviously enhance alumni’s career opportunities. At the same time, their participation in the program would directly increase both the diversity in the cultural background of the student cohort and the situated expertise in predominantly Muslim traditions and thus contribute twofold to the methodological foundations of the research approach.

The important take-away here is that the participation of both Israeli and Palestinian students is inherently justified by the methodological approach of the research agenda underlying the program of study, even without a development agenda. While tuition fees are political anathema in Germany and certainly would be out of reach for the vast majority of students in precarious circumstances such as the Palestinian territories, one could well imagine an identical master program offered at the usual rates required of students at a comparable Anglo-Saxon university on its professional, academic and research merits alone. The small mental leap of connecting the emergent subject matter of a research field with simultaneously emergent instructional technologies, in contrast, opened tangible avenues towards growth, substance and impact in a win-win situation for education providers and students alike, through an expanded option space for educational and development interventions within a previously inaccessible area.

Museum of Islamic Art, Picture: IEIW

Previous collaboration projects of the founding scholars reinforced the observation that the relevant community of interested specialists and potential students was small and scattered throughout the world. If digital technologies could facilitate such a program in an online format, while eliminating the constraints of geographic distance and political borders, they should be leveraged into such an undertaking that much sooner. Students could apply, enroll and participate without having to relocate. Visiting lecturers could be contracted as virtual faculty without necessitating either travel arrangements or the dreaded administrative overhead on both sides associated with teaching a semester at a foreign university. Their strong teaching commitment would be assured if the convenience of an online program related to their particular specialty thus had the added benefit of providing them with a carefully selected audience of highly qualified and intensely motivated students. Blended learning could be leveraged for this project with the primary focus, not on digital didactics, but on the organizational mode of a learning space that would be difficult and much more costly to create with nondigital means.

Viewed in this manner, the particular specialization on Islamicate discourses in medieval history itself made the project eminently suitable for an online learning pilot. Testing the promise of extending graduate educational opportunities in such a fragile context with the help of digital tools would be a relatively costly and fairly risky proposition in any subject. But the risks of potential failure, wasted resources and damaged reputations would have been much greater in a prominent field with many competitors. For a pilot project, the narrow disciplinary focus in a specialized humanities niche was therefore no hindrance, but helpful indeed.

Potentials of the blended learning mode

Passing the strategic goals of the project through the funnel of practical considerations provides the vagueness of initial ideas with a workable, concrete shape. Ideas developed during the years preceding the IEIW grant proposal congealed into the contours of a blended learning program, with some on-site components and about 80% mediated e-learning content. As is typical for innovative higher education projects, the chosen model of instruction was not based on a thorough examination of research in digital pedagogy or empirical data on learner behavior in the region. It was intuitively clear to the founding scholars, from both their teaching practices and intercultural experiences, that the kind of quality they aimed to maintain in the program could not be achieved by remote instruction and e-learning alone. Some elements of direct interaction between instructors and students on-site would be needed to allow the corporeal dimension of diversity in a social setting to manifest itself.

With regard to the intended learning goals, only if participants were immersed in the tangible qualities of dealing with the otherness of their fellow students would they reflect on their inventory of communicative skills to the point of being able to address them. More practically speaking, since this would likely be the first academic online program for most participants, some in-person onboarding would prove useful in assuring the effective use of online formats right from the outset. The basic outline of the program thus rested on hypotheses derived from a mixture of teaching experience, subject matter expertise, practical considerations and intuition.

Similarly, the inferred demand for the imminent program could not be based on any concrete data of actual demand. There was no formal equivalent to market research activities that one would undertake for the launch of a consumer product. Instead, the educational deficit was diagnosed systemically, as a general need for advanced professional degrees, with the added skill set for intercultural dialogue as a bonus in the politically conflicted environment. Modern technologies of distance learning were thus expected to alleviate some of the systemic deficits of higher education in fragile contexts by expanding access to learning opportunities. In addition, the mediated nature of the program would broaden potential access far beyond the immediate surroundings of al-Quds University (AQU) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJ) to include students from predominantly Muslim countries, eventually including students from Iran, Afghanistan, Egypt, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Peru, the United States and the Netherlands.

This extension of reach and access comes with a price, however. Imagining an on-site format at FUB that would be comparable to the IEIW online program in learning goals and curriculum, the reality would be that expenditures per student would inevitably be higher. Even though the original project setup had proposed a trilateral cooperation framework with the two universities in Jerusalem, it had been the clear expectation from the beginning that, for the foreseeable future, the bulk of pedagogical and technological investment would have to take place on the German side of the triangle. If, over time, some of the workload could be distributed more equitably among the three partners, it should be seen as a substantial success in improving fragile institutional structures of the target region. It furthermore stands to reason, though, that such a shift is more likely to be the effect of structural changes in the economic and political environment of the partner universities, rather than the trilateral academic cooperation itself.

To gauge what costs are appropriate for such a course of study, it is illuminating to imagine an identical graduate program without the availability of digital tools. No matter which version of the program a given student would enroll in, assuming course designers and program administrators have done their work properly, her learning outcomes in terms of personal knowledge and skills upon graduating would be identical. An alumna would be expected to demonstrate a competent mastery of graduate academic skills, a comprehensive analysis of intellectual exchange in medieval Islam with other religions, and a grasp of suitable research methods for historic and cultural inquiry.

All other things being equal, one would expect the on-site program to require the smaller investment of the two, if only by making superfluous the cost of an online classroom, content digitization, training and support. Yet this reduction in cost would be irrelevant, because the program would now be inaccessible to the very students it aimed to attract. Academic talents could be recruited from many different parts of the world, but not from the fragile contexts of the Middle East and Palestinian territories in particular. A more sensible comparison value to determine the program’s efficient use of material resources would therefore have to include the costs of full scholarships, including the cost of living, that would then enable students from fragile contexts to reside in Berlin for the duration of the program.

Even if such funding were available, it would still leave open the question whether an on-site course would be preferable to the blended format. Student feedback during the project has repeatedly confirmed the contributing effects that distance-learning has had for the development of intercultural communication skills. The primarily web-based modules additionally included three face-to-face phases per academic cycle, with seminars and workshops in Còrdoba and Berlin. The shared social space during these phases strongly encouraged students and teachers to interact in discussions, classes and examinations within an inevitably intercultural setting. But looking back, students reported that the distancing effects of the blended learning formats were crucial for them to practice these communication skills gradually and rehearse unfamiliar roles of interaction within the setting of a more protected, mediated space.

The benefits of using blended learning formats, then, lie not in a reduction of costs, at least where access to higher education and training is concerned. Digitalization and mediatization of instructional content in this case does not lead to a lesser form of learning when compared to on-site teaching. It is an investment into educational access that opens pathways of learning for students in the target region that otherwise would remain unavailable.

Scoping and scaling the program parameters

Using digital tools for access to fragile contexts does not preclude additional constraints influencing the design of a successful, sustainable educational program, with the most immediate being actual learner demand. It is a defining feature of fragile settings and precarious living conditions that the ability to plan for the long term is limited and that individuals are forced to heavily discount the future compared to the present. The target audience of intended students can be expected to carefully consider investing material resources, personal effort and the time necessary for a commitment to the program, weighing opportunity costs such as foregone income. From the perspective of future applicants, fragile contexts create such economic pressures that the opportunity cost for participation in a two-year program is simply prohibitive. The two year duration common for German master’s degree programs in the post-Bologna landscape would severely limit the ability of students from fragile contexts to participate and successfully complete the degree. Recruiting a suitably divergent mix of students to the program would depend on communicating a persuasive value proposition.

Moreover, a two-year program is also difficult to align with available funding frameworks. Public administration on a state and federal level, as a rule, adheres to a fiscal year whose budget cycles begin in January, creating substantial compatibility issues with higher education whose project funding follows the academic year beginning in October. The initial grant covered a generous project duration of three years, with contingency funding at least implicitly dependent on a proof-of-concept, namely measurable success in the defined outcomes. Calculating a minimum of one semester for program design, staff and student recruiting and operational ramp-up, then, a first cohort of applicants enrolled in a two-year program would just barely be able to finish their degree within the initial funding cycle. An assessment of program viability within the initial funding period would prove difficult, creating a substantial risk for continued provision of funds for program and staff. Moreover, the second cycle of a two-year program would overlap with the end of the initial funding period, creating uncertainty for students and commitment pressure for the funders. The obvious alternative, a one-year master program, would be able to deliver a proof of viability, but risked running afoul of the expectations for academic substance and rigorous practice that were the focus of the research unit and its standing in the history department as well as the strategic perspective of the host university.

As a practical result, a decision regarding the overall program design was made to develop the curriculum for a one-year program with the option to write the master thesis subsequent to the two-semester course phase. The Freie Universität Berlin (FUB) would offer the 12-month MA program, calculated in conformity with Bologna standards to a total 60 ECTS credit points, for an annual cohort of 20 students, the majority of whom would be recruited from the Middle East region. Due to the short duration of the program, part-time enrolment was not an option; participation required a full-time commitment for the duration. With this format, two full cycles could be completed within the initial funding phase, allowing for sufficient substance to evaluate the program’s academic quality and structural sustainability (see Figure 6).

After the initial grant, contingency funding would be granted in subsequent installments based on quality monitoring and outcome evaluation for students in the initial academic cycles. An outcome evaluation would obviously have to focus on the academic outcomes, because the development impact would take substantially longer to manifest itself in a tangible manner. Even with two cohorts of alumni and a third one enrolled, empirical assessment of the project’s higher education outcomes were just as difficult to capture. Any measurement of learning achievements has to consider the generally unclear relationships between teacher choices for curriculum and learning design on the one hand and the individual learner’s motivation and learning skills on the other. Both variables are strongly interdependent and notoriously impact actual learning outcomes. To put it plainly, some students may perform exceptionally well, in spite of a poorly designed curriculum or instructional design. And some students may perform poorly, even though curriculum and instruction are beyond reproach.

Recent research has therefore suggested that mechanisms and formats for adult teaching and learning should be more explicitly considered in the context of design. Adopting such a designer perspective might prove helpful, especially when examining the role and the uses of technology in education (Laurillard, 2013). Indeed, when instructional decisions are made and suitable means of teaching are developed, we do not usually investigate them with the scrutiny of a theoretically derived hypothesis awaiting empirical verification. Instead, the standard approach is to define the desired learning outcomes, to then select the means to achieve them, and to subsequently specify criteria defining learner success, such as grades. We use this information to judge student performance - but we do not typically judge the instructional design.

In terms of empirical verification, this is tantamount to hypothesizing that certain teaching methods will lead to desired learning outcomes, measuring the resulting grades, and in the event of unsatisfactory outcomes, concluding that the students were deficient, but leaving the hypothesis of instructional scaffolding intact (Laurillard, 2013, p. 5). In practice, of course, an experienced and capable instructor will question and continually improve her teaching repertoire and, just as obviously, a course that every single participant fails will be just as critically examined as a course in which all participants graduate with the highest possible marks. All of this reinforces Laurillard’s observation that the problem of teaching is not one of theoretical science, but one of the “right fit” between instructor, students, subject, setting and methodology to achieve certain goals, in other words, a problem of design and a science of the artificial (Simon, 1969). Assessing the quality of an instructional design invariably involves reflection on the assumptions for the underlying impact model, that is, the relative importance of teachers and students on the one hand and environmental variables on the other (Fabry, 2015).

Standard evaluations9 of learning outcomes in higher education programs focus on effectiveness and efficiency; by definition, they are able to provide only limited insights into the operational decisions that later turn into important milestones on the road of program design – both for success as well as for setbacks. That many of these lessons are lost is evidenced by the fact that the history of higher education innovation in Germany cannot be written without acknowledging the many successful pilot projects that withered away once the initial funding dried up.

It is therefore critical to keep in mind that any attempt to reliably quantify the successful leverage of learning outcomes into career advancement might overburden the scope of a one-year program. Numerous factors well beyond the control of project design and successful graduation influence subsequent alumni career trajectories. They run the gamut of their individual life situations, from individual life choices and family situations to the impact of geopolitical shifts on the local labor market.

More appropriate for assessing the effectiveness of the program than a well-intentioned but unrealistic output-based perspective is therefore an input-based assessment. As in judging any other design artifact, the question then becomes one of the “right fit”. Does the instructional design and the structure of an individual’s learning journey through the program suitably correspond with the expected learning goals? The key measure of assessment of the IEIW learning design, in other words, is whether achievable skills for professional leadership and intercultural dialogue have been realistically defined, controlled for at the beginning of the program, problematized and practiced in an adequate manner and assessed at program completion with sufficient reliability.

Notes

8. Lest anyone think this a trivial point, the reader should remember that 20th century history of digital networks takes place overwhelmingly in research settings at publicly funded universities.

9. The DAAD employed the author of this publication as a consultant for the e-learning component of the IEIW program, during the 2017 evaluation conducted by SysPons GmbH, Berlin.

References

- Araya, Y. (2013). State fragility, displacement and development interventions. Forced Migration Review, 43, 63–65. http://www.fmreview.org/fragilestates/araya.html

- Clark, R.C., & Mayer, R.E. (2016). e-Learning and the Science of Instruction (4th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley & Sons. http://doi.org/10.1002/9781119239086

- Davies, L. (2011). Learning for state-building: capacity development, education and fragility. Comparative Education, 47(2), 157–180. http://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.554085

- Fabry, G. (2015). Wie können wir Lehrqualität messen? In R. Egger & M. Merkt (Eds.), Teaching Skills Assessments (Vol. 42, pp. 73–90). Wiesbaden: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-10834-2_5

- Gross, Z., & Davies, L. (Eds.). (2015). The Contested Role of Education in Conflict and Fragility. Rotterdam: SensePublishers. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-010-9

- Krämer, S. (2018). Der ‚Stachel des Digitalen‘ – ein Anreiz zur Selbstreflexion in den Geisteswissenschaften? Digital Classics Online, 4(1), 5–11.

- Laurillard, D.M. (2013) Teaching as a Design Science. London: Routledge.

- Mcloughlin, C. (2016). Fragile States. Birmingham: GSDRC, University of Birmingham, UK. Retrieved from www.gsdrc.org

- Merrill, M.D. (2012). First Principles of Instruction. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons.

- OECD. (2013). Think global, act global. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2015). States of Fragility 2015. OECD Publishing.

- Raunig, M., & Höfler, E. (2018). Digitale Methoden? Über begriffliche Wirrungen und vermeintliche Innovationen. Digital Classics Online, 4(1), 12–22.

- Simon, H.A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Vogeler, G. (2018). Kritik der digitalen Vernunft. DHd, Köln: Verband Digital Humanities im deutschsprachigen Raum e.V. Retrieved from http://dhd2018.uni-koeln.de/

- Whitchurch, C. (2018). From a diversifying workforce to the rise of the itinerant academic. Higher Education, 18 (Supplement 1), 35–52. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0294-6

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top