6. Mapping learning paths

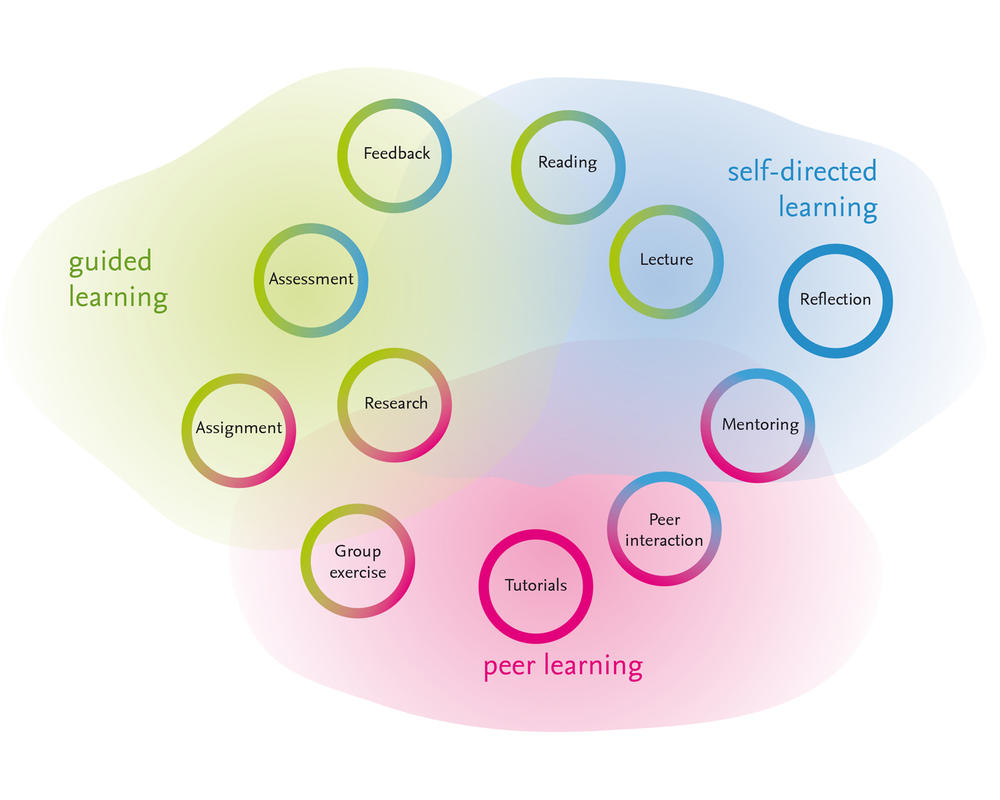

Figure 12. Course formats and assignment types corresponding to different learning goals and different modes of social interaction were mapped onto the curriculum and its blended learning mode.

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

Introduction: Course formats and assignments

The relationship of higher education and digital technologies in Germany is fraught with misunderstandings and skepticism. The current generation of lecturers were among the first to have access to email and the web during their own graduate education. These digital modes of communication were in their infancy available almost exclusively in a university or research setting. Prevalent uses concentrated mainly for administration, research and course management. They fundamentally changed the way the university library functions, but did not eliminate the blackboard or the lecture hall. Applications for teaching and learning were limited to the distribution of digitized content such as syllabi, lecture slides or term papers via Learning Management Systems (LMS) and communication via email.

Today, instructors are generally outmatched in digital literacy and skill by the current crop of students entering university equipped with tablets instead of laptops. Growing up as „digital natives“ (Prensky, 2001) they tend to reject paper in favor of always-on mobile devices for note-taking and navigate e-books and databases for studying with flexibility and ease. A recent wave of excitement for digital forms of instruction has given rise to the idea of disruption in higher education and a concomitant unbundling of the services provided by traditional brick-and-mortar universities (Anderson & McElroy, 2017).

Along with a potential for change, this discourse is widely perceived as threatening and unhelpful in making these technologies welcome in academic teaching and learning. Broadband access and the use of mobile devices have indeed spread globally, minimizing apparent digital divides, even in economically fragile regions. Looking beyond the level of technical infrastructure reveals that access to digital technologies must not lead to an assumption of uniform literacies and uses (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2014). For university students outside technical fields such as engineering in particular, there is a clear tendency for conventional and limited use of digital technologies (Margaryan, Littlejohn, & Vojt, 2011). University instructors thus enjoy academic freedom regarding the incorporation of recent developments in their scientific field and a high degree of flexibility regarding local teaching conditions, as long as their instructional and assessment strategies comply with the study and examination regulations, which have been formalized at the departmental, school or university levels.

Digital skepticism is arguably most pronounced among educators in the humanities. It is unclear what, if anything, technology can contribute to the particular set of instructional modes prevalent in the tradition of continental Geisteswissenschaften. What role should digital tools play to emulate, let alone improve, the discursive method of Socratic dialogue, the careful dissection of concepts and the critique of coherent argumentation? These kinds of learning arrangements, according to academic dogma, require docents well-versed in the subject matter, ready to contemplate its known and heretofore unknown facets with a community of curious learners. Digitizing texts is helpful for easier access to source material and the literature, digitizing the classroom into a mediated setting seems to offer a lesser learning experience, as anyone who has sat through a 90-minute recorded lecture in front of their laptop can attest.

Part of this critique can be attributed to a simple misunderstanding that results from a focus on instruction and teaching. The notion of e-learning or blended learning from this perspective is often framed as a technologically enhanced or digitally virtualized version of established teaching practices. Capturing a lecture on video and making it available for online viewing is the paradigmatic example: An established, but somewhat ephemeral format of on-site instruction (lecturing) is mediated to add permanence (the possibility of time-shifted and location-independent review). Higher flexibility for the students has a trade-off, however: Social presence of both the lecturer and fellow students, the effect of spatial and temporal contiguity. Emergent terminologies such as digital learning or technology-enhanced learning and the related discourses of technology in higher education helpfully emphasize a focus on learners and learning instead of teaching. Considering that the pre-eminent property of digital technologies is the loss of spatial and temporal contiguity - an effective shrinking or evaporation of space and time - this terminology centers on the learners and makes accessible a discussion of the effectiveness of learning practices.

Learning mode and feedback channels

In light of these impulses for looking beyond tools and content to changing processes and parameters, the technological aspects of the IEIW instructional design might at first glance appear somewhat pedestrian, when compared to the mushrooming of digital educational formats during the project lifetime. Early considerations mentioned in the grant proposal for using avatars, virtual reality, MOOC and recent innovations soon gave way to a fairly conventional digital environment of online lectures, videoconferences, discussion forums, bulletin boards, messaging, chat and email. Of course, some of these design decisions can be attributed to constraints within the university environment in Berlin as well as the digital realities in the fragile contexts of student life-worlds.

Crucially, though, learning formats were selected for the instructional design and developed with each academic cycle based on an adequate fit with the intended learning outcomes. It proved highly productive to think about digital technologies not as replacing or disrupting established educational practices and formats, but as complementing and extending them. This attitude permitted instructors and course designers to examine which of the familiar learning (and teaching) practices were in fact effective for the diverse community of IEIW students, the subject matter of medieval history and the skill set associated with intercultural dialogue.

The learning elements that comprise the curriculum had to adequately provide participants with the wherewithal to achieve multiple learnings goals — academic, intercultural, professional. What is of particular relevance here, is that the explicit definition of these three different dimensions of learning departs from the usual distinction between „hard“ professional skills and „soft“ skills (social interaction, communication, discipline, reflection, honesty, self-consciousness to name but a few). There is an explicit recognition in the original program design, that these conventionally labeled „soft“ skills are equally, perhaps even more important than the „hard“ skills related to the subject matter of becoming a trained scholar in medieval history.

The problem here is that the distinction between professional and leadership skills on the one hand and skills of intercultural dialogue on the other is analytic; in practice these abilities are closely connected, intertwined and mutually constitutive. While suitable instruction, scaffolding and encouragement may be provided within the program, the resulting learning outcomes will vary on an individual level where they will take shape depending on personal background, prior education experience. While the positive development of graduate academic skill, leadership and action competencies has been shown in program graduates again and again, there is an inherent tension between the two dimensions of evaluation.

LMS, picture: IEIW

An effective training in intercultural communication is not easy to achieve. Yet it is often assigned a low value as a learning outcome because it is classified as a soft skill. Providing effective training in advanced graduate studies is also acknowledged as successful. Yet it does not suffice for satisfaction of the evaluation criteria, for failing to provide a sufficient impulse for employment in the nonacademic labor market.

The implications of the islamicate world as a heuristic concept corresponds to a strong interdisciplinary perspective on the subject matter and therefore explicitly defines interpretative and communicative skills of intercultural dialogue among the learning goals. An expected challenge to be addressed within this system, due to the diversity inherent in program parameters, were intercultural frictions on the participant side. The fragile context of the Middle East exacerbated some of these discrepancies into veritable obstacles, both for individual students and organizational stakeholders.

A higher degree of diversity in the student cohort translates into additional requirements for instructional design. Rather than covering the subject matter of the curriculum in a conventional ex-cathedra format, instructors have to instead effectively address heterogeneous backgrounds, different learning strategies and educational expectations that learners bring to the classroom setting. Coupled with a higher degree of responsibility for learning outcomes, faculty has to embrace a more differentiated teaching input if the goal is to maintain overall quality. Learning goals of a given module as well as the overall program have to be „constructively aligned“ (Biggs & Tang, 2011) with activities that promote efficient student learning. As an additional consideration, the resulting instructional toolkit containing suitable didactic methods and pedagogic formats needs to be selected with the additional constraint of working in a mediated online setting. These requirements for the instructional design of the program make clear that pedagogic substance had to take precedence over technological innovation. Program modules largely followed a distance-learning approach (rather than a natively digital-learning approach) that relied on virtualized versions of established, familiar formats of instruction so as to focus on the complexities of unfolding learning processes, rather than on the complexities of digital didactics and tools.

Mentoring, tutoring and scaffolding

In the current environment of digitally native millennial students, it is no longer helpful to distinguish between learning about digital technologies and learning with digital technologies, as was the case during the first decade of online learning. A more fitting assumption is that students learn about these technologies along with the topic, not in a smooth linear progression but in distinct stages that involve different degrees of interactivity with instructors, tutors and fellow students. A large body of existing research on this topic focuses on students progressing through an individual course, not an entire degree-granting program.

Even where multiple iterations of online learnings over several years have been used, studies are confined, often for practical reasons, to learning and community-interaction processes in single-course instances based on textual artifacts. Even the widely-cited five-stage model developed by Salmons for investigating the importance of „e-moderating” is constrained by this approach (Salmon, 2011). So little is systematically certain, about the learnings formally associated with one format over the other. Nevertheless, they are used every day by competent instructors and motivated students, who - for all intents and purposes – seem to achieve an overall satisfying degree of learning outcomes.

Teachers, picture: IEIW

Successful completion of the IEIW program, as a case in point, implied that graduates had acquired a whole set of additional skills due to the instructional design relying on online and blended distance learning. The flexibility that comes with technology-enhanced learning has a flip-side in the discipline required from participants to maintain motivation and engagement. The protective space for social interaction that enables higher learning, which is inherent in intramural, on-site education, has to be re-created or at least approximated by each program participant individually. Mastery of this dimension of the learning goals implies not only sufficient technological savviness, it is a solid reflection of successful learning strategies, and a high degree of self-discipline and self-organization. Taken together, this bundle of competencies can indeed be a strong contributor to professional employment and leadership capabilities.

Lest the reader gain the impression that students receive a degree in intercultural skill, it should be carefully noted that these skills are part and parcel of a regular disciplinary Master degree program. The additional dimension of intercultural dialogue is emphasized throughout this publication, because it was crucial for project success and its important role in graduate training is often underestimated or outright overlooked. Having said all that, the disciplinary training in philosophy and cultural studies is state-of-the art and requires a dedicated effort. Program alumni exhibit excellent scholarly skills, as evidenced not only in the quality of their final thesis but by the fact that many of them have continued their academic careers after being accepted as PhD candidates at prestigious institutions.

The annual graduation rates are a first indicator of academic substance. For the 2013/14 cohort, the graduation rate was 85%, for 2014/15 net was 75% and for the subsequent cycles 2015/16 and 2016/17 it continued at around 95%. Meanwhile, IEIW graduates have completed two dissertations at the Universities of Cyprus and Teheran, respectively, and have been accepted in PhD programs at Freie Universität Berlin, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv University, Leiden University, University of Chicago, Yale University, Harvard University and Princeton University. IEIW alumni who have returned to the labor market have benefited from their degree in their careers at educational institutions, international agencies and NGO, interreligious cultural institutions, museums, libraries or in journalism. Among their employers are the Goethe-Institut e.V. and the GIZ, the British Council, the United Nations, the Swedish Theological Institute and Euronews television.

First-hand learnings and impressions

If a picture can stand in for a thousand words, an anecdote can likewise serve to illustrate and illuminate the complexities entangled in real-life situations that defy abstraction. With this intention, the following observations shared by the project team are included here without editorial comment.

The Intervention of World Politics: In July 2014, Israel launched a military operation in the Gaza strip. The MA program was then approaching the end of the academic year of its first cohort – and as we thought, maybe also its last. The colloquium was organized and scheduled for August. We could be neither sure, if the Israeli and Palestinian students would continue to participate in the online sessions nor if the in-class session in Berlin would still be taking place. Naturally, we addressed the escalation right at the start of the first session after the beginning of the operation. The students reacted in a surprising way. They asked each other if they were ok, asked for casualties in the family, one student pointed out that in case of a bomb alarm he would need to run quickly away from the session to reach the next shelter. This kind of mutual assurance stayed for the rest of the conflict and the summer colloquium in Berlin.

On 31 May 2017, a bomb exploded near the German embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan. An immediate effect of this event was that Germany completely withdrew its diplomatic personnel due to the acute life danger – and so did nearly all diplomatic representations of states belonging to the Schengen Area. This also meant that no other embassy would take over the consular tasks of Germany, as it is usual practice among diplomatic missions. With the summer colloquium in August approaching, this meant that our Afghan participant was facing serious problems in getting hold of a visa. Either he would have to travel to Islamabad (which was not an option) or we would have to identify at least one still running consulate of a Schengen state in order to approach them for support. This was the case for the Norwegian representation. Thus, we approached them parallel to our student applying for a visa through them. Luckily, they were willing to support the participant with a visa – understanding the singular circumstances. Besides, we provided the student with a letter that he could show at immigration in case there would be questions.

Fly little drone: During the introductory week in Cordoba, one of our participants who is a hobby photographer and videographer had taken along a drone. In the evening at around 11.00 pm, I got a phone call by a furious fellow student that I should come to the hotel of the students, as police was there having confiscated the drone and questioning our participant. Though the drone had been registered in Spain ahead of the journey, there had just been a legal reform that forbid using them at all if not with a specific permit. Not having been aware of this recent change, our participant had it flying across the Mezquita and the ancient Roman bridge which caused a passerby to call the police. The officers simply had to be convinced of the actual reality of an online degree program offered by a German university bringing together students from the Middle East organizing a first meeting with each other in Cordoba due to the historical connection of the place to its topic. Naturally, the student got back his drone and there were no consequences whatsoever.

Expectation Management: Managing expectations and communicating clearly are the key ingredients for the success of an online degree program in a highly intercultural context. Independent of the actual whereabouts of the participants, the heterogeneous composition and the individuality of personalities will confront any organizer with challenges. It must be clear right from the start, which rules are carved in marble and which are more flexible for discussion. There are some starting points, we learnt and tried to keep in mind throughout the program:

- It is risky to presume that people know what they have to do.

- Keeping participants permanently in the loop by a regular, transparent and pro-active flow of information is important.

- Consistent and reliable information is key, as are approachability and respect. This starts with the first contact.

- It is recommendable to encourage participants to communicate directly and immediately – if need be by using confirmation messages and/or deadlines. Assuming compliance to deadlines will most certainly be disappointed and expecting direct communication about it as well.

- Simply the fact of being approachable as an organizational team will make one the addressee for complaints, critique and (more or less justified) desires. One has to learn how to cope with it – registration to the best gym in town could be one option.

- There will be differences that cannot be solved or “healed”.

Emotion Management: We manage the diversity of the group and the concerns that arise due to the fragile context in which our students learn by offering our students space and time to approach us with all kinds of problems or issues related to their studies. Sometimes, this invites students to discuss very personal issues with us:

After I had welcomed the students for an online session and the Professor began his lecture, one of the students contacted me through the private chat function. “Sorry,” he wrote “today I am only physically present at my laptop, not mentally present in the class”. He explained that his father had died two days before. He told me that his mind was full of grief and fear regarding his new responsibilities for his family at home in South Asia, which made it impossible for him to concentrate. I proposed to him to skip today’s online session. He replied that he rather stayed online with us, than being all by himself in his room in Berlin. We continued to chat for about half an hour about his emotional situation. Then he closed the chat, writing that now he feels a bit better and fit to divert his mind by following the discussion that what was going on in the digital classroom.

[by Imke Rajamani]The olive scandal: It was our first introductory session into our Moodle learning platform. Sixteen eager faces and their laptops had been exploring the system with me. Working for the first time with Palestinian and Israeli students, I had been apprehensive: Would they work well together? I needn’t have worried – it was a joy to sit at learn with them. Until that one exercise. Looking back at it today I shake my head at having been so naive. You see, I had created an example course which I worked through with them. And of all the topics I could have chosen, I made it about olives.

It was quite a nice course. Videos of growing olives. Choice activities ‘What olive-colour do you prefer’. Bogus papers with Lorem-Ipsum text, supposedly researching the fine points of olive-eating. And – here is where it happened – an assignment to hand in ‘a nice picture of an olive tree’. Oblivious of its symbolic meaning for Palestinian resistance, I clicked through the pictures students had handed in. Quipping; little fun remarks here and there and handing out fake marks.

And then I saw the following submission:

Photo: Nasser Ishtayeh

I could almost hear our initiator’s and my colleagues’ hearts stop from the couch of the other side of the room. I tried not to miss a beat. And honestly, I don’t remember what I said to make the group laugh. Somehow everyone kept their cool. We moved on. The example course next year was about cookies. Looking at all the present-boxes of fresh cookies in our pantry, I think it was a good switch.

The old man and the web: Sidney Griffith is a most distinguished Catholic priest and respected researcher. Incidentally, he is one of the greatest minds in the area of knowledge in which the students of the IEIW program can obtain their degree. The program was incredibly lucky when we successfully convinced him to accept a teaching position with us.

There was an obvious challenge though, not easily addressed. This eminent scholar looks back on almost eighty years of life on this earth and decades of classroom teaching. Naturally, I was a little apprehensive when we were preparing his lecture. How would he fare with our online classroom? Could someone like him successfully adapt to teaching an online course?

As life goes, my ageist prejudices where unfounded. ‘I’m having a senior moment’ was his favorite sentence every time he thought he was too slow. But he wasn’t. He found his way around the virtual classroom just about as well as colleagues half his age. Even if he had to pinch his eyes at times to read the small user interface.

Picture: IEIW

Sidney didn’t do modern didactic methods. He didn’t need to. In his deep and well-measured voice he told the stories of intellectual history so captivatingly, many students later evaluated his course as the most interesting and insightful experiences of the whole year.

I took three lessons away from this experience. First, a good user interface profits from a few big buttons to press. We developed a special Emotiboard plugin, pictured above, to achieve just that effect. Second, rules of good instructional design are important for online learning, but they take secondary role if the charisma and authority embodied in the teacher’s personality is transmitted succesfully. Last not least, Sidney Griffith proved beyond a doubt, if such a proof were necessary, that no-one is too old to teach online and no subject is too steeped in history to elude the digital modes of learning.

[by Roman Rehor]References

- Anderson, T., & McElroy, B.W. (2017). Disruptive Pedagogies and Technologies in Universities. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 380–389.

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A., & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers & Education, 56(2), 429–440. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.09.004

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. http://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

- Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

- van Deursen, A.J., & van Dijk, J. (2014). The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media & Society, 16(3), 507–526. http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813487959

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top