7. Translating and buffering workstreams

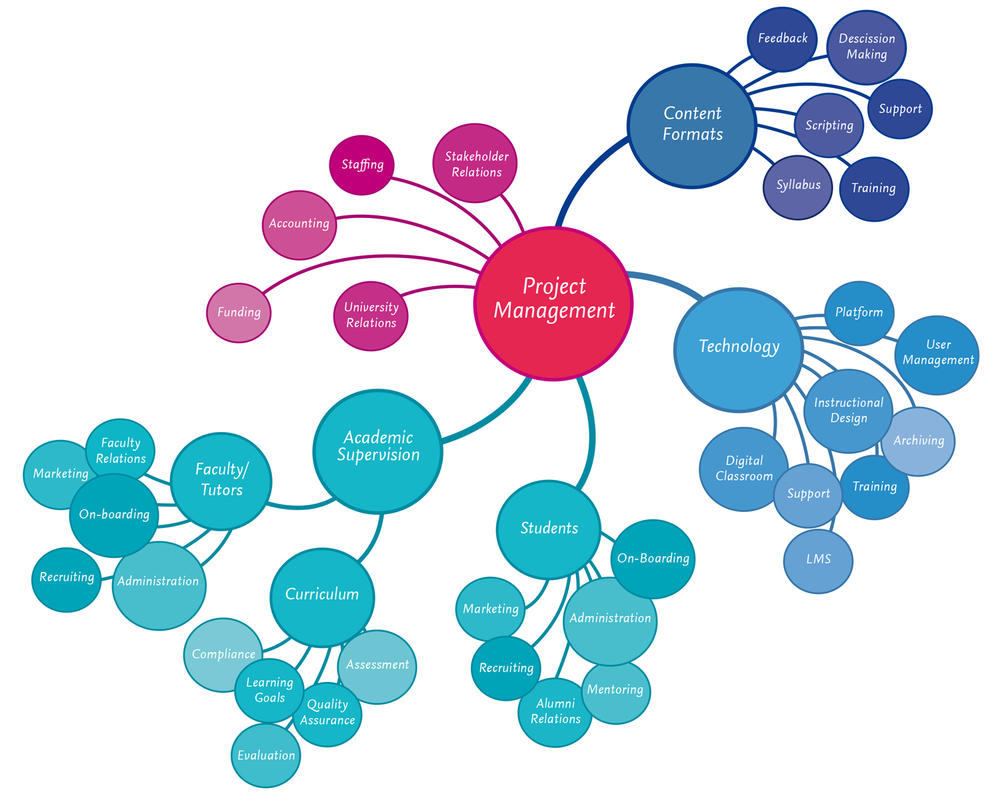

Figure 13. Dividing tasks and corresponding expertise enables efficient parallel workstreams

Image Credit: Katharina Neubert

Introduction: Digital didactics and media production

Due to geopolitical factors well beyond what founders and funders could have anticipated, let alone controlled, the prospects of inter-religious dialogue in the region look bleaker today than they did at program inception. Yet at the end of the funding period in 2019, the empirical impact of the program in the fragile context of the Palestinian territories is small, but not immeasurably so. A concrete number of alumni have re-entered the labor market with high-quality academic degrees, although a closer inspection reveals that recognition of ECTS credit points and the issued diploma can face local hurdles.

During the project lifetime, the political context of the Middle East developed a dynamic that eroded the foundations and potentials for a trilateral co-operation between the three universities involved in Israel and the Palestinian territories. It is crucial to note that successful execution of the project was possible only because it was initiated and operationalized on the departmental level and through the involvement of personal networks among individual researchers. It stands to reason that the deterioration in the overall geopolitical climate would have pre-empted project continuation had it been institutionalized at the level of an official trilateral co-operation between the universities as originally intended.

These obstacles to co-operation rooted in the context external to the project itself were manifest first in the contractual arrangement between the universities. It quickly became clear, that an openly trilateral agreement between all three universities was politically untenable for both HUJ and AQU. Instead, FUB entered into two separate bilateral agreements with each of the university partners, to circumnavigate the tensions between the two partners in the region, effectively providing a neutral political buffer that would effectively permit co-operation in a tripartite constellation, but avoid burdening either partner with the formal requirements of a contractual relationship across the regional cultural lines of conflict.

In conflictual and fragile contexts, a pre-eminent skill is diplomatically cladding a project in intentionally intransparent language to maintain a credibly neutral position and avoid the political frisson that would nip it in the bud. Note, for example, how the very title of the IEIW program is an exercise in obscuring and re-accentuating the project’s intent. If it was called „Online Master to train Palestinian and Israeli graduate students in intercultural dialogue for professional advancement“ it would be more true to its intent, but entirely unhelpful in terms of marketing and recruiting. Note that „intellectual encounters“ is an apt description of the subject matter, the research method and the general skill-set offered by the program. Likewise, the term „islamicate world“ is a no less elegant circumnavigation of loaded terminologies in reference to both the focus of the research and the recruitment of the student cohort.

By the same token, evaluation cycles demand the continuous alignment of strategic project goals with higher education outcomes and development policies related to „fragility“. But an overt embrace of such terminology can overlook the changing realities in a development project that take place parallel to project runtime. Evaluators should therefore be aware of possible scope creep during evaluation processes over multiple academic cycles.

Evaluation criteria need to be adapted in the context of a particular program, but changes in the overall development or education discourse, for example, are easily super-imposed onto project outcomes after the fact. A more productive approach is to develop evaluation criteria together with the project team so as to be able to consider indicators that emerge during the project runtime, especially when a longer time horizon is being considered.

More importantly, they need to keep in mind that a number of complex assumptions and hypotheses were formed at the outset of this project. Measuring indicators and outcomes alone documents the effectiveness of these assumptions as translated into operational practices. But ex post it is easy to forget that their original validation or contextualization amounts to an equally valuable output in terms of project learnings, of which this handbook aims to capture a few.

Academic quality and sustainability

The IEIW project addresses a systemic obstacle in the Middle East and fragile contexts more generally, namely the lack of post-graduate academics and qualified decision-makers in executive positions, who are able to communicate effectively across religious and political borders. In part, such shortages result from too few available formalized educational opportunities with the capacity to provide this kind of intercultural communications skill. Moreover, it is a result of limited access to those opportunities that do exist.

Institutions of higher education in the Middle East are certainly home to individual proponents of intercultural education opportunities. On an organizational level, however, they must invariably align with the prevalent political agenda of state policy and the religious realities of surrounding social structures. The creation of transcultural or interreligious initiatives within the region cannot count on institutional encouragement nor support. Even where such programs exist it is difficult to populate them in a continuous fashion. General access to advanced training programs is often limited for marginalized groups to begin with, or is practically ruled out by security concerns or economic hardship for potential students from these backgrounds.

A remarkable aspect of program design was formulated during one of the interviews with representatives from AQU partner university. As a university, AQU had formally withdrawn from the stakeholder network. The political tensions had flared up to the point where a boycott of the program became the only viable political position for al-Quds University. Sari Nusseibeh had resigned as its president in the summer of 2014, just as the pilot iteration neared completion, and the program he had created fell victim to a more hardline institutional approach taken by his successor. As the third pillar in the trilateral co-operation these unforeseen and rather sudden developments posed an existential threat to the program, as the project could neither replace the institutional partner with an alternative partner nor continue without a similarly strong grounding in the Palestinian territories for the numerous internal and external reasons outlined in Section 1 above.

At this point, the loosely coupled organizational structure of universities (Weick, 1976), so often a stumbling block for strategic innovation, was actually helpful in devising a solution to this dilemma. Though no longer president, Sari Nusseibeh, resumed his post as a professor at AQU with the associated teaching activities. Helped by his standing in the research community and his reputation for personal integrity, numerous instructors, researchers and administrators at AQU maintained strong personal working relationships with the project team in Berlin on an informal, non-institutional level in spite of the official boycott. Relying on these personal networks was necessary to provide active support in the annual recruitment and admissions process for new students as well as the on-going mentoring support and in alumni relations.

It was clear to all of these individuals, that their university, as a prominent public stakeholder in the on-going conflicts of the politico-cultural landscape, was officially unable to condone a trilateral co-operation with an Israeli university any longer in light of the increasingly hostile political climate in the region. But those that continued a personal engagement with the program were steadfast in their conviction, that continuation of the project and similar initiatives were contributing to an improvement of the selfsame situation. Accepting such contradictions as inherent to cyclical motion of cultural and political conflict, they were easily able to separate and smoothly navigate different levels of formal commitment to their organization (and the political position it represented) and their individual engagement for research and teaching with motivated students in their professional field.

The fragility of state and educational institution in Palestine was thus in a way helpful in that individuals enjoyed a sufficient degree of leeway for this kind of informal interaction. But as much as these partners appreciated the main thrust of the project in terms of education and training, they were baffled by repeated efforts from various project partners to achieve a higher degree of visibility for the program’s academic output and a stronger push for institutionalization. It was clear from their point of view, that once their continued clandestine activities were publicly exposed, they would have to cease (and possibly negate) them immediately. Their expectation towards the partners in Germany especially, was that their informal engagement would be countered with an understanding that continued engagement would have to be handled discreetly until the political environment became more conducive to co-operation. When confronted with the desire of funding agencies to increase the visibility of project outcomes by marketing and public relations activities and to re-establish a formalized relationship albeit at departmental level with the program, an interlocutor at AQU finally responded, with some exasperation: „Formalization and visibility would spell death to this program.”

From the Palestinian partner’s point of view, the quality of program design and student motivation were beyond doubt and continued to draw them into co-operation. For the project to continue its educational outreach and achieve its political goals on an individual level for students and instructors, however, it was equally clear to them that on an organizational and institutional level, it needed to very much stay below the political radar. What is important to note, is that the neutral space for approximation and co-operation created virtually by the online learning environment does not translate into the socio-politically fragile circumstances of participants’ surroundings. While the digital tools can provide them with virtual access to educational opportunities, they ignore at their peril the impact a commitment to such a program carries for students, teachers or administrators within their actual life-worlds.

The important distinction here is between high academic standards on the inside that do not translate into mainstream acceptance on the outside. In terms of outside acceptance, academic excellence is sidelined by the political tensions affecting the Middle East region, so that for the program to achieve its political goals, it was well-advised to maintain a peripheral position.

Third space versus the chair principle

After the Bologna reforms, the European university as an institution in 21st century knowledge society no longer enjoys the protective aura of an ivory tower that is publicly funded but restricted to social elites, who rely on its monopoly for the transmission and expansion of knowledge to acquire training and skills (Seyfarth & Spoun, 2011). Increased scrutiny for its internal administrative mechanisms, the university is becoming more similar to regular organizations: Its public funding means increased accountability and transparency for its modes of governance. The competition from alternate education providers and the increased mobility of students results in a competitive environment and demands clear value propositions. The overall contributions expected of the university on a personal, regional and social level have moved beyond research and education to include economic development.

Across the European university landscape, a concomitant growth of the number and roles of university administrators is clearly observable relative to the number of academic instructors and researchers (Baltaru & Soysal, 2017). This trend has long been familiar in the context of the United States higher education system, and is commonly associated with the growing orientation of higher education institutions toward increased autonomy and an expansion in the scope of its mission. It is an unsurprising development in light of the different kinds of specialized knowledge associated with the different mission of a modern university and the overall growth in student numbers. It has been shown to correlate across geographical and institutional differences with a university undertaking „entrepreneurial” activities in new „markets” rather than structural pressures of budget cuts or deregulation. A growing body of literature examines these emerging professional roles that are not part of the administration in the traditional sense, but academic staff not directly engaged with either research or teaching (Schneijderberg, Merkator, Teichler, & Kehm, 2013), as academic professionals working in the „third space” of higher education institutions (Schneidewind, 2016; Whitchurch, 2008).

Colloquium 2016, picture: IEIW

Yet, in spite of these changes, organizing on-site academic instruction continues to follow a „chair principle” that turns out to be ill-equipped for the administration of distributed online and blended learning (Kerres, 2001). The professorial chair enjoys a (surprisingly) autonomous and central authority in defining, operating and assessing curricular knowledge. The chair is thus responsible for quality assurance according to disciplinary conventions, and in this role is (loosely) supervised by a community of her scholarly peers.

In contemporary e-learning projects, additional processes to on-site instruction arise in areas such as IT platform administration, media production and distribution, project management and reporting. The resulting number of complex tasks requiring specialized know-how that is more or less unrelated to the academic subject matter at hand, results in numerous different operational roles. But routines engendered in the history13 of the „chair principle” tend to inhibit effective division of labor and instead encourage a „lone warrior” mentality, where all aspects of the project are to be executed within the respective department, often by docents themselves. Kerres (Kerres, 2001) points out that this one-stop-shop approach is markedly distinct from processes of media production pervasive in the industry, where in-depth expertise leads to a narrowly defined division of labour among individuals involved.

In the context of a university, the resources invested by academic staff into acquiring the necessary expertise can hardly expect to match them in professional quality. Yet it is rarely an option to outsource IT administration and media production entirely to external service providers, due not just to prohibitive costs and slow turn-around times, but because learning materials need to be flexibly adaptable to different contexts and learning demands. So technical decisions can be handled in-house and do not become constraints for pedagogic practices and learning progress, a modicum of expertise and capacity within the team is helpful for technical support, as noted above, as well as for the administration of the IT learning platform and for the production of multimedia digital learning materials published there. Having acknowledged the broad portfolio of skills required, a clear division of labor is crucial for sustainable workflows, even more so for small project teams. Moreover, an argument can be made to keep the technical aspects (such as platform configuration, software tools, communication channels) limited to a clearly defined set of functionalities that can be maintained without the help of specialized expertise. In turn, project funds are better spent on staff development as well as student/faculty training for the use of easily accessible and simple digital tools, rather than on investment into sophisticated software requiring subsequent expenditures for external support services. While the former approach tends to accumulate useful skills in-house over time, the latter approach results in a less sustainable model of recurring fixed costs.

Different kinds of expertise are required to deal with media producers, central student administration, the international office or the departmental oversight commission. Rather than spreading this kind of expertise around it is best to rely on a one-face-to-the-customer approach to provide continuous, reliable streams of communication to external partners. As long as sufficiently effective practices for internal team communication are in place, it is more efficient to consolidate these information streams internally and manage them consistently.

These activities and relationships are negotiated within a university department and its neighboring organizational units, but belong neither to academic teaching or the routines of administrative bureaucracy. In their entirety, they are usefully understood as constituting a „third space“ (Pohlenz, Harris-Huemmert, & Mitterauer, 2017; Whitchurch, 2008) of overlapping, sometimes conflicting identities, roles and responsibilities. With roots in post-modern human geography (Soja, 1996) and post-colonial discourse (Bhabha, 2012), the idea of a third space acknowledges that a (long-term) cultural transformation within an organization such as a university takes the (short-term) empirically observable form of individuals having to address the concrete dissonances created by encounters and imperatives of different cultural spheres. Plainly put, the logics of public administration (compliance, efficiency, transparency, standardization, legal frameworks) inevitably clash with the demands of intercultural online teaching (ingenuity, experience, experimentation, innovation, contextualization, design, heterogeneity) and these clashes manifest themselves on the individual level with conflictual interchanges among colleagues or contradictory loyalties within an individual’s decision-making and actions.

The logics driving different workstreams must be negotiated within the third space, which makes this growing area of university activities a contested territory by definition. This implies that many of these conflicts cannot be neatly dissolved by compromise or translated by dialectic synthesis into a common approach. Just as often, the task for project management is to sufficiently buffer them from each other for each to continue undisturbed and uninhibited on different, non-intersecting planes.

Notes

13. The tradition of this organizing principle dates back, of course, to the religious authority associated with the physical chair of the bishop in medieval Europe’s monastery schools (W. Clark, 2008).

References

- Baltaru, R.D., & Soysal, Y.N. (2017). Administrators in higher education. Higher Education, 76(2), 213–229. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0204-3

- Bhabha, H. K. (2012). The Location of Culture (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203820551

- Clark, W. (2008). Academic charisma and the birth of the modern research university. Chicago: U Chicago Press.

- Kerres, M. (2001). Medien und Hochschule. Strategien zur Erneuerung der Hochschullehre. In L. J. Issing & G. Stärk (Eds.), Studieren mit Multimedia und Internet (pp. 57–70). Münster: Waxmann.

- Pohlenz, P., Harris-Huemmert, S., & Mitterauer, L. (Eds.). (2017). Third Space Revisited. Bielefeld: UVW.

- Seyfarth, F.C., & Spoun, S. (2011). Die Vertreibung aus dem Elfenbeinturm: Selbstverständnis, Attraktivität und Wettbewerb deutscher Universitäten nach Bologna. In: C. Jamme & A. von Schröder (Eds.), Einsamkeit und Freiheit (pp. 192–219). München. http://doi.org/10.3196/2194584511641138

- Schneidewind, U. (2016). Die “Third Mission” zur “First Mission” machen?, Die Hochschule, 25(1), 14–22.

- Schneijderberg, C., Merkator, N., Teichler, U., & Kehm, B. (2013). Verwaltung war gestern? Frankfurt: Campus.

- Soja, E.W. (1996). Thirdspace. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Weick, K.E. (1976). Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. http://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

- Whitchurch, C. (2008). Shifting Identities and Blurring Boundaries: The Emergence of Third Space Professionals in UK Higher Education. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(4), 377–396. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00387.x

Chapters

1. Higher education and development in fragile contexts

2. Shaping a higher education intervention

3. Supporting individual learning outcomes

4. Cycling and re-cycling hypotheses

5. Balancing stakeholder relationships

6. Mapping learning paths

7. Translating and buffering workstreams

8. Negotiating innovation and compliance

↑ top